California has a math problem.

Nearly a decade after Common Core math standards were adopted in California, the majority of K-12 students are not yet meeting grade-level benchmarks, and Black and Latino students are underrepresented in rigorous accelerated programs. Now, a state-led recommendation to overhaul math pathways is meeting pushback.

On Wednesday, the state’s Instructional Quality Commission faced a barrage of comments from parents and teachers opposing a controversial rewrite of the California Mathematics Framework, voluntary guidance that aims to help schools, teachers and textbook companies implement the state’s Common Core math standards.

The commission voted to incorporate approved changes, including to specify guidance for districts around accelerated math tracks and removing references to a controversial study.

The framework is now headed for a second public review in June, and the commission will review additional changes if the State Board of Education requests it. The framework will go before the State Board of Education in November.

The draft document emphasizes alternative math courses, such as data science and modeling, and structures mathematical topics by grade rather than distinct courses. But a flashpoint in the debate is the recommendation that students take the same math classes in middle school through sophomore year of high school, rather than placing students into advanced or traditional math courses beginning in sixth grade.

The recommendations also question the concept of student giftedness, saying the notion has “led to considerable inequities in mathematics education. Particularly damaging is the idea of the ‘math brain’— that people are born with a brain that is suited (or not) for math,” the document reads.

On Wednesday, members of the commission shared experiences they said made the framework’s goals resonate with them.

“I was placed on the advanced math track, and I took algebra in eighth grade,” said commission Chairman and high school history teacher Manuel Rustin. “I raced through math just like other students who are determined to get into the UC system. But eventually, math became something I couldn’t identify with anymore. It felt like a rat race to memorize procedures and formulas. … Seeing what we have here, I saw myself all over it.”

Groups, including the California Teachers Association, the Education Trust-West and the California STEM Network, expressed support for the draft framework. But others, such as the California Association for the Gifted, said it hinders opportunities for students, and individual teachers and dozens of parents called in to the meeting to oppose the changes at Wednesday’s virtual hearing.

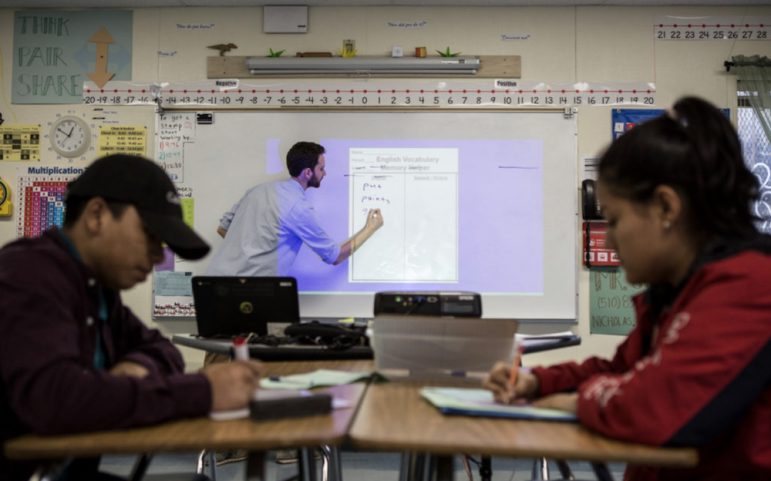

Some, including state Sen. Ben Allen, D-Santa Monica, pointed out challenges with differentiating teaching for a class where students are at widely different levels, especially as California faces a shortage of professionals choosing to become math teachers. Many parents cited fears over their child’s unique abilities being shortchanged without pathways for students identified as gifted.

“I’m concerned about the proposals for the elimination of advanced math classes in the middle school years,” said Wendy Marcus, a parent of three students in Moorpark Unified in Ventura County, including a daughter she described as gifted. “Putting advanced students with average and below average in the same class does not work. A lot of times they just toss those kids aside and give them extra work.”

A Los Angeles Unified parent and graduate named Victor said he supports parts of the framework but rejected the idea of “limiting access to accelerated math in public schools,” he said. “Advanced math is the pathway that so many first-gen students like myself used to reach the middle class.”

The framework does not require districts to eliminate honors math programs, nor does it direct schools to hold students back from rigorous math courses. Districts that choose to remove accelerated courses in middle school could still offer calculus and other advanced math courses required for STEM pathways for juniors and seniors.

Many supporters of the new proposal point to examples, such as San Francisco Unified, which in 2014 voted to remove accelerated middle school math classes.

Five years after the policy change, the San Francisco Unified graduating class of 2018–19 saw a drop in Algebra 1 repeat rates from 40% to 8%, and 30% of the students in high school were taking courses beyond Algebra 2.

However, two parents on Wednesday argued that “de-tracking” efforts in their districts have not made any noticeable improvements for disadvantaged students, and, instead, have removed opportunities for students to excel.

“If we don’t have explicit guidance here around how to accelerate those students who need more or need to move faster, you will have districts that don’t implement the frameworks,” said commission member Linsey Gotanda, deputy superintendent of Palos Verdes Peninsula Unified School District. “That’s not what we want as a commission.”

On the heels of a fierce debate over a statewide ethnic studies curriculum, state education officials are now finding themselves trying to address both misinformation and the very real concerns parents have over their children’s future with mathematics. Headlines, such as The Wall Street Journal’s “California leftists are trying to cancel mathematics,” are already stoking fears.

“Misinformation is sort of the reality of today and the future. We dealt with that with the ethnic studies curriculum, as well,” Rustin said. “But this issue of equity and race and racism in classrooms is not going to go away.”

Some opponents argue the framework attempts to inject math with critical race theory, an academic approach that argues that the history of slavery and segregation lives on in current laws and social structures, perpetuating racism in the U.S.

While not explicitly mentioning critical race theory, the framework points to research that supports teaching math through a social justice lens. It also suggests using real-world examples to make math lessons more relevant to students’ lived experiences, encouraging multiple ways of showing an answer. And it calls out how race, class and gender play a role in the messages students receive about their place in the math class.

Several comments from the most recent public review push back, in particular, on a report cited in the framework titled “A Pathway to Equitable Math Instruction,” which calls for dismantling racism and white supremacy that surfaces in mathematics through tracking, course selection and intervention rosters, as well as finding only one “right” answer.

The commission agreed to remove references to the study from the draft framework on Wednesday, stating it was inconsistent with teaching to the standards.

Still, some parents feel uneasy about a subject they believe lives outside the realm of race and politics.

“This math framework is a giant step backwards and anti-merit indoctrination,” one parent from San Diego said. “Don’t turn math into an ideological battleground.”

Like all of the state’s subject guidelines, the math framework is regularly revised on a seven-year cycle. The updated framework has been in development since 2019, and it will be presented to the State Board of Education for approval in November 2021. Along with a 60-day public comment period from February to April 2021, input guiding the document came from four focus groups of teachers along with a focus group of students to provide insights into their experiences with mathematics and courses.

The proposal still has a way to go to earn public approval: About 53% of those who provided comments during the public review rated the framework’s guidance for instruction for all students as “poor.”

After the public comment period, commission member Kimberly Young added that students without the opportunity to take accelerated classes were largely missing from the discussion.

“We didn’t hear from people who have been harmed by tracking. We need to make sure we are representing diverse learners who don’t have people to speak for them,” Young said. “I’m really looking at this document to do that.”