For the first time ever, the vast majority of California families say their kids have personal computing devices that they can use for school. But even after a year of distance learning, thousands of students still don’t have a computer or access to the internet at home.

After schools had to close their buildings last spring due to Covid-19, most pivoted online, forcing districts and state officials to rapidly shore up resources for extra computers and Wi-Fi hot spots for students who didn’t have their own devices or internet access at home.

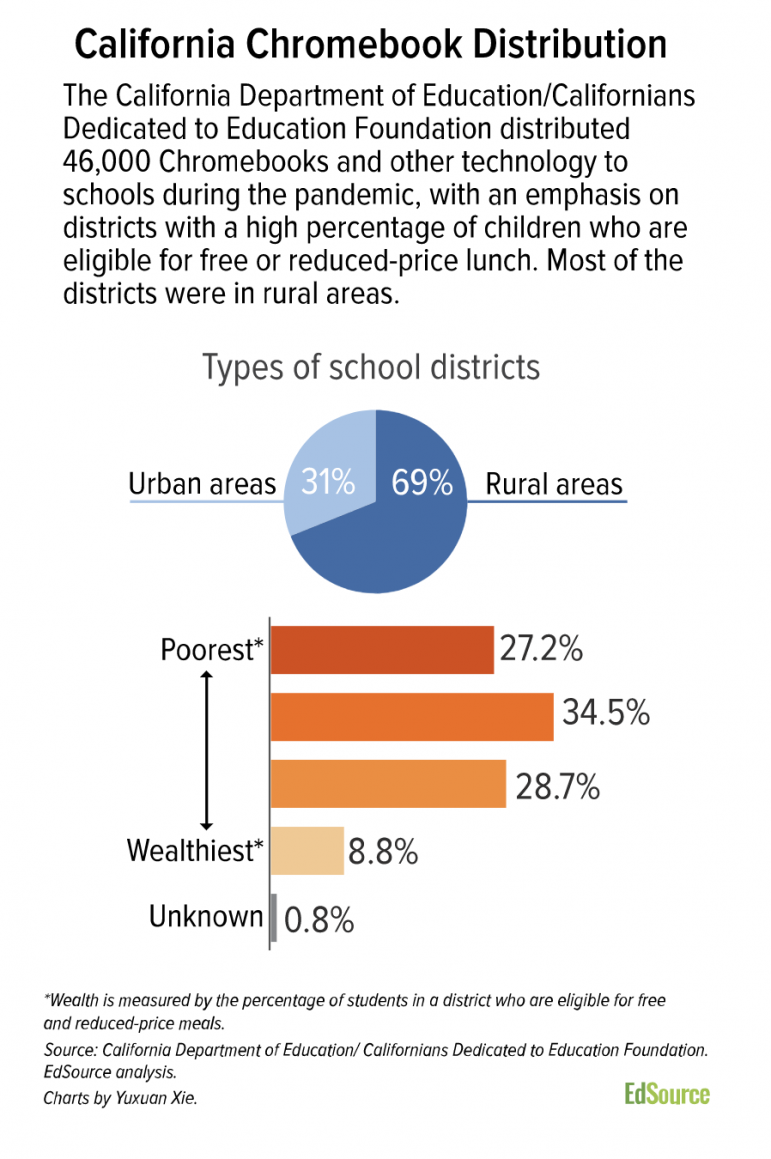

Following an outcry from districts, the Californians Dedicated to Education Foundation, a private nonprofit fiscal manager for the California Department of Education, launched the Bridging the Digital Divide Fund to raise money to buy technology. The fund prioritized small, rural districts with high numbers of low-income students.

Overall, the devices went to rural districts, as well as some larger districts serving high numbers of low-income students, according to an EdSource analysis of data from the California Department of Education. About 69% of the districts that received devices are in rural areas and predominantly serve low-income families. Nearly half of all devices went to those districts, and the remaining went to larger suburban and urban districts with high portions of low-income students. Many of the districts with high percentages of low-income students also have high percentages of English Learners, another student group the program targeted.

The Bridging the Digital Divide Fund was one of the few avenues through which the California Department of Education provided tangible devices to districts when schools closed, though several other simultaneous efforts took place to provide students with technology. In the midst of a global shortage of laptops, the program funded and distributed 45,884 Chromebooks, 1,103 Google management licenses, 70 wireless mice, 15 printers and four $500 drawing tablets, according to data provided to EdSource.

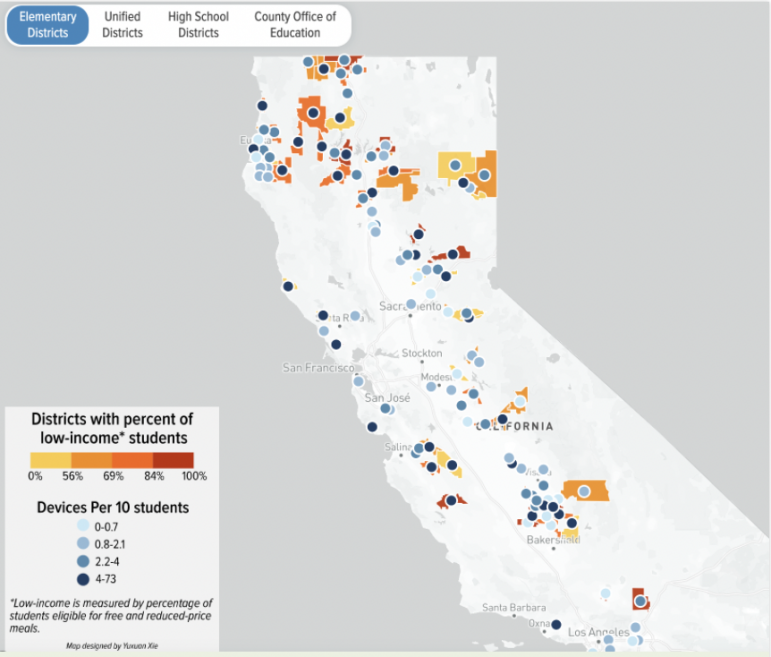

EdSource map: California Chromebook distribution during Covid-19

View our interactive map displaying the concentration of Chromebook distribution at California schools, including data on how many low-income students attend.

In addition, the California Department of Education received 100,725 donated hot spots from T-Mobile, with Google paying for service for three months, and other device donations directly to districts from technology companies including Lenovo, Hewlett Packard, Microsoft and Amazon. It also negotiated purchasing programs with distributors that districts could use, in addition to nearly $2.1 billion in federal CARES funding that California districts used to facilitate distance learning.

Despite efforts to appeal to Silicon Valley’s big donors, however, hundreds of thousands of students are still estimated to be without computers at home, according to recent data from the California Emerging Technology Fund and the University of Southern California, which conducted a statewide survey of 575 California families in February and March.

As of March, 95% of California families with school-age children said each of their kids had a device to use for remote classes, according to the USC and technology fund study. About 3% said a computer was available but shared, and 2% said they didn’t have a device. Most of those without a device are Spanish-speaking families, the study found.

Other estimates, however, suggest an even greater portion of students are still without devices after more than a year of distance learning. Using data from the Census Household Pulse Survey from April 2020 to March 2021, the Public Policy Institute of California found that only about 80% of California students have access to computer devices in spring 2021, up from 67% when schools first closed in March 2020.

Since last summer, the Californians Dedicated to Education Foundation raised nearly $18.4 million for the Bridging the Digital Divide Fund from philanthropists and tech companies including Google, Amazon, AT&T and VIPKid, a Chinese online tutoring company.

Several of the state’s largest urban districts found support from tech giants in their backyards, such as Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey’s $10 million technology gift to Oakland Unified. Los Angeles Unified set up its own low-cost program with Verizon to provide internet service to students’ homes and, more recently, the district passed a motion to continue to fund and monitor computer and internet access for students beyond the pandemic.

The amount and type of devices purchased through the digital divide fund ranged greatly due to districts’ reported needs. Santa Paula Unified, for example, serves about 5,000 mostly low-income students living among Ventura County’s orange groves and received more than 1,000 Chromebooks last fall totaling $336,537. Others received much fewer, such as Mother Lode Union Elementary in El Dorado County, where only about 1,000 students are enrolled. The district received about a dozen Chromebooks.

Today, nearly 85% of California residents use a computer, laptop or tablet to access the internet from home, up from 78% in 2019, according to the USC survey. The share of residents who can only connect to the internet on a smartphone dropped from 10% in 2019 to 6% in 2021.

The authors of the report directly attribute that increased computer access to the role schools and programs such as the digital divide fund played this past year in getting devices to the students who needed them most.

“We see a very significant impact of the provision of computers and tablets from school districts. About 75% of parents said their kid has a tablet or computer provided by the districts, most said after the pandemic started,” said Hernan Galperin, principal researcher for the study.

Inequities in technology existed long before Covid-19. So when computers become the doors to the classroom during the pandemic, district and state officials had to act quickly to find solutions.

Using findings from a survey by the Small School Districts Association last summer that gauged districts’ device needs, the California Department of Education and its nonprofit partner worked with Office Depot to order and distribute the devices in bulk to 214 districts and 47 charter schools, about one-fourth of all California school districts, according to data provided to EdSource.

Districts that responded to the survey were then called to verify their needs, and small and rural schools were prioritized as devices became available. Once those districts were contacted, state education officials reached out to midsize districts with high percentages of low-income students and English learners to connect them with devices.

“These donations were the first pieces of the puzzle to getting our students connected and able to learn from home,” said Mary Nicely, senior policy adviser to State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond, who has been steering the department’s efforts to close the digital divide this year.

“No one is calling us saying they need devices. It’s connectivity, that is the big issue,” Nicely said, referring to the even greater need for affordable high-speed internet service across California.

Acknowledging that many students still don’t have devices or connectivity, she added, “Schools shut down, so it was hard to figure out how to get to students. I think we did the best we could with what we had.”

One reason why gaps in technology access are so tricky to identify in California is that districts are not required to collect or report data on student connectivity. But that will soon change: The California Department of Education recently hired a researcher to gather and map information from districts on student technology access, Nicely said.

For districts like Santa Paula Unified, the donated devices were crucial during a crisis. Even though students are beginning to return to class, the donations sped up the district’s pre-pandemic efforts to provide all students with computers and digital skills.

Nearly 90% of the district’s 5,270 students come from low-income families, and 35% are English learners. Just before the pandemic, most students struggled to access the internet at home, said Michael Colmenares, the network technician for Santa Paula Unified. Some could only log on through a cellphone, which was difficult to do any schoolwork on, and many didn’t have any type of device.

“It was a real moment of real desperation,” Colmenares said. “At the time, we had no problem in terms of affording devices, it was just finding availability. We were buying whatever we could get our hands on. So those extra devices from CDE (California Department of Education) went to sites immediately, and it covered a huge portion of our students.”

But more computers also led to more problems. Many parts of California still lack broadband infrastructure and struggle to attract internet service providers, which historically have avoided low-population areas. And now, districts face new, ongoing costs for repairs and replacement devices, plus internet service for students using district-managed hot spots.

“There were always places where service wasn’t as strong or someone wasn’t communicating what they need. We were constantly pounding the pavement putting out surveys and announcements,” said Elizabeth Garcia, principal at Santa Paula High School. “We did a lot of home visits where we replaced hot spots that weren’t working. We always had staff on-site to address technology issues.”

A handful of bills now making their way through the California Legislature aim to reform broadband funding in California and increase the money available to address ongoing connectivity gaps. Thurmond is sponsoring two of those bills, SB 4 and AB 14.

Those efforts could also get a boost under President Joe Biden’s $2 trillion American Jobs Plan infrastructure proposal, which would direct $100 billion to extend high-speed broadband infrastructure to reach 100% coverage nationwide and reduce the price of broadband.

“All those kids who couldn’t do homework from home or continue education at home aren’t able to participate, and that’s not right,” Nicely said. “Even when the pandemic is over, this is not over.”