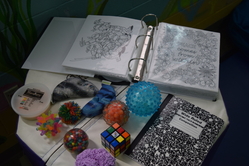

When a young person enters the de-escalation room in the Sacramento County Youth Detention Facility, they’ll find dimmed lights, bottles of lavender, orange and other essential oils, an audio menu featuring the rush of ocean waves and other calming sounds, along with squeeze balls, TheraPutty, jigsaw puzzles, and an exercise ball to bounce on.

Sometimes, with a teen’s permission, “We’ll put a weighted blanket on them, just to give them that hug that feels good, since we can’t give them [real] hugs in our facility,” says Valerie Clark, the probation officer who oversees the room. Giving hugs violates the protocol requiring that staff maintain healthy boundaries with their young charges. But “especially if someone is highly upset and just really crying,” Clark explains, the blanket can be a comforting substitute.

Since it first opened to youth in November 2016, the de-escalation room has been a refuge for kids feeling overwhelming anger, grief, sadness, and anxiety, who are either referred by staff or can request a visit. They stay in it anywhere from 30 minutes up to two hours.

The room is one example of how the Sacramento County Probation Department is shifting its culture to be responsive to adolescent trauma. In 2016, the department sponsored a countywide summit on trauma and the adolescent brain. This February and March, 330 employees from the Youth Detention Facility, and 155 from Juvenile Field, Placement and Court divisions, were trained in the roots of trauma and how to respond to it. And five members of the probation leadership were certified as trainers in trauma-informed practices. The training includes learning about how trauma in childhood can trigger the brain into fight, flight and freeze; can cause depression and lead to disruptive behaviors, and how they can build strength and resilience in the youth they serve.

Prior to having the de-escalation room, says Clark, youth would be sent to their individual rooms when they were disruptive or upset. “This way they have the opportunity to regain control of their emotions and behavior so they can go back to their programs instead of [having to stay] in their room alone with their thoughts,” she explains.

An impetus for the room, known as the Multi-Sensory De-escalation Room, was legislation that was signed into law in California in 2016, says Shaunda Cruz, the deputy chief of field services at the Sacramento County Probation Department and one of the department’s trauma-informed champions.

“The legislation recognizes the impact that trauma, and obviously the impact of coming into a facility, has on young people,” she says. The law, which was sponsored by former California state Sen. Mark Leno, limits the use of solitary confinement for minors in detention facilities to four hours, and allows it only when juveniles’ behavior is considered a safety threat and less restrictive options have been exhausted.

Around the same time that the legislation was being developed, members of the county probation department and juvenile court staff were working on a capstone project through a justice reform collaborative out of Georgetown University’s Center for Juvenile Justice Reform. That’s where the idea for an MSDR emerged, says Ruby Jones, assistant chief deputy of the Sacramento County Youth Detention Facility.

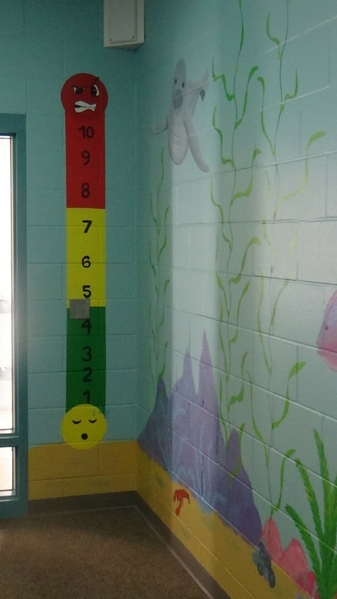

Since the MSDR opened, 2,212 of the residents have spent time in it. Upon entering and leaving, each person is asked to pick a number that indicates their current state on an emotional scale that’s painted on the wall: 1 to 4 means doing well; 5 to 7 indicates feeling stressed; and 8 to 10 shows that a young person is really upset and ready to explode. Data show that the room is making a difference. After a respite within in the room, the kids’ scores on the emotional scale have dropped an average of 4.5 points by the time they leave, with most reporting that they feel like they’ve returned to a calmer state. (Youth also go there to work with Clark on strategies to stay calm in preparation for a high-stress event, such as an impending court date.)

Besides gauging their emotional state, Clark asks the youth open-ended questions to ascertain their strengths, triggers, coping skills, and who on the staff they feel a rapport with.

“And I’m also asking them how about outside the facility? Do you have at least one positive support person?” she says. She then writes up a confidential report and shares it with the rest of the probation staff.

The department believes that the de-escalation room is among the first of its kind in a youth detention facility. It’s well documented that youth in the justice system, who are disproportionately people of color, have experienced adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). According to a report in the Justice Policy Journal, between 73% and 95% of justice-involved youth have experienced multiple types of violence and traumatic events before they ever have contact with the justice system.

The Annie E. Casey Foundation, which has been a leading advocate for a healing approach to juvenile justice, points out that, “study after study has shown that these prison-like settings are no place for kids.”

The foundation has explored a number of approaches to the problem, including healing retreats to examine the wounds that have led to incarceration; restorative justice, in which offenders and victims meet in an effort for youth to take responsibility for their actions and practice empathy and compassion; and home placement with caring adults in lieu of confinement. Its data show a drop in juvenile confinement across races in sites participating in the program. For African American youth, juvenile confinement shrunk between 25% and 65%, while national rates fell by only 8% over the same period.

The majority of the young people who end up staying in detention have been charged with serious offenses. In general, youth arrested for low-level crimes such as violating probation, and a first-time nonviolent offense are typically cited and sent home, while others stay for just a few days before their hearings, says Maria Gonzalez, the chief deputy of the Sacramento County juvenile facility.

“If there are gun charges, we’re more likely to keep them,” she says. “If we can’t get hold of a parent, we’re going to keep them. If it’s a domestic offense and the victim is still in the home, we’re more likely to keep them.” The facility also houses young people who have not been arrested, including foster youth who are waiting for a placement in a group home or with a family. The average stay is 30 days, says Gonzalez, but the figure is misleading because of the residents who may be there for a couple of years awaiting trial.

A decade ago the number of youth in detention in Sacramento County was much higher, around 400 at any given time. “In the last year or two our average has been pretty consistent at around 100 residents,” says Jones. Currently, she says there are 97 boys and nine girls.

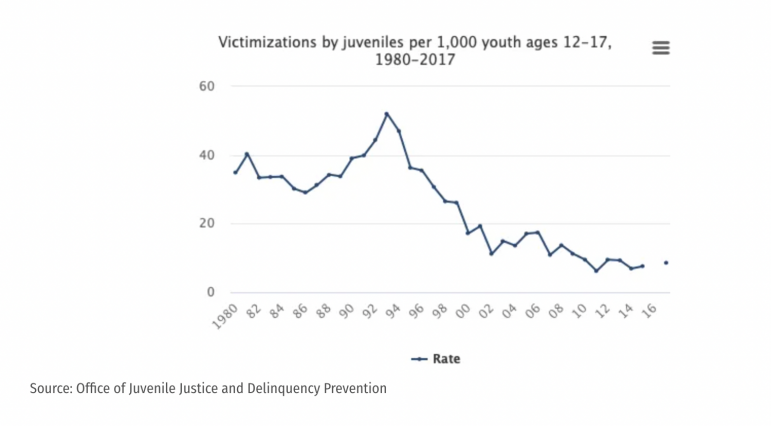

On a national level, juvenile violent crime has declined remarkably since 1993. The rate of youth held in detention facilities or camps in Sacramento County has dropped by more than half, from 187 per 100,000 in 2009 to 85 per 100,000 in 2016, according to the most recent data on county facilities by population from the Center for Juvenile and Criminal Justice.

Youth who have been confined to the Sacramento County Youth Detention Facility say they like the de-escalation room and counseling. Sixteen-year-old James was one of the youth who used the MSDR, which the confined juveniles call “the cove.” He was referred by staff members on his unit, he says, “because I was going through a lot. I was getting into a lot of arguments with staff and causing problems in the unit. And I was having breakdowns because I couldn’t have any visits from my family on account of the corona [virus].”

When he was released last October, he was referred by probation to the Self Awareness & Recovery (SAR) program, which supports youth and adults involved in the justice system by providing mentors and workshops on trauma and healing, according to SAR Director Daniel Antonio Silva. (To protect their privacy, we’re not using the real names of teens interviewed for this story.)

Like many of the youth who end up in detention, James, who is Latino, had experienced a host of ACEs that started when he was an infant. “My real mom left me, and my dad, he went to prison” he says. From the time he was a year old, he lived with his grandparents.

Due to systemic racism, a Latino child is twice as likely as a White child to have a parent who is incarcerated, and a Black child is five times more likely than a White child to have a parent incarcerated, according to a report by the Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality.

James listed other traumas that had shadowed his life. His early teens marked the first time — but not the last — that someone shot at him on the street. He also struggled with drug use, to which he turned to cope with pain of his past.

When he went to the cove, James recalls that he chose to sink into the depths of a bean bag chair and that he asked for jazz music to calm his frayed nerves. He also recalled the dim lights and the conversation with the woman officer who was in the room with him.

“We talked about the problems I had going on in the unit and how to work them out, and what I can do so that I don’t come back to Juvenile Hall,” he says. The officer counseled him to seek out new friends who were less likely to get into trouble, encouraged him to stay in school, and asked him questions to identify tools he could use to calm himself if he were triggered again after he left the room.

“I told her that praying made me feel better, so she told me to pray. That really stood out to me,” the teen says.

The experiences of James are right out of the landmark Centers for Disease Control/Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences Study, which identified 10 types of childhood adversity — such as experiencing parental divorce or separation or having a parent who was incarcerated — with risks of substance use and other coping behaviors.

The study, which looked at 17,000 adults, found that ACEs are remarkably common — most people have at least one. People who have four or more different types of ACEs — about 12% of the population — have a 460% higher risk of depression and a 700% higher risk of becoming an alcoholic, compared with people who have no ACEs. (ACEs Science 101; Got Your ACE/Resilience Score?)

The epidemiology of childhood adversity is one of five parts of PACEs (positive and adverse childhood experiences) science, which also includes how toxic stress from ACEs affects children’s brains, the short- and long-term health effects of toxic stress, how toxic stress is passed on from generation to generation, and research on resilience, which includes how individuals, organizations, systems and communities can integrate PACEs science to solve our most intractable problems.

Fortunately, brains and lives are somewhat plastic. The appropriate integration of resilience factors born out of PACE concepts — such as asking for help, developing trusting relationships, forming a positive attitude, listening to feelings — can help people improve their lives.

The Sacramento County Youth Detention Center is teaching staff how to recognize and ease the ACEs their young charges have experienced. Since 2017, every young person who has been arrested and brought to the facility is screened with the Child and Adolescent Trauma Scale for a number of childhood adversities, including physical and sexual abuse and exposure to community violence.

The screening tool is used to help staff identify the additional support a young person needs, and the scores are shared with the juvenile courts. If the scores and staff interviews with new arrivals reveal a high level of ACEs from violence, they’re assigned to one of two trauma units that house anywhere from eight to 19 of these youth and offered a 10-week, in-depth trauma-oriented curriculum.

The course was developed and implemented in 2012 by clinicians with the CAARE Center, part of the Department of Pediatrics at UC Davis. It covers what trauma is, including ACEs, common reactions to experiencing ACES, how to identify and cope with strong emotions, and how to identify and build healthy, positive relationships.

Considering that the course is designed for teenagers, Dr. Brandi Liles, a licensed psychologist at the UC Davis Children’s Hospital CAARE Center, and Dr. Dawn Blacker, had a hunch that the youth would be more inclined to pay close attention if they sweetened the deal — literally. They gave each of the kids a piece of candy and asked them to focus on it for the first mindfulness exercise.

“And they really focused on being in the present moment,” says Liles. “We started with that one, because we figured we’d get pretty good buy-in. We also have some grounding mindfulness techniques, including breathing exercises and noticing and paying attention to things in the room. That’s really helpful for kids who dissociate or get dysregulated.”

Although final results from the research are not yet available, the trauma course seems to be yielding some positive results. “Kids who maybe were very quiet in the beginning and distrustful of the process are really opening up,” says Liles, who launched the project along with co-associate director Blacker.

“They’re also starting to support each other,” says Liles, “which has been very powerful. We began with just giving positive feedback, and then [we noticed that] all of the youth were giving positive feedback to each other. Things like, ‘Thank you for sharing.’” Liles also gives them support for taking responsibility for outbursts: “Like, hey, when you got mad and stormed out, you know, you were able to come back.”

Nathaniel, who has been and in and out of detention since he was around 13, is one of the teens who went through the trauma curriculum. Before he took the course, he remembered worrying that his experience in the youth detention facility would be like those described by incarcerated men in the prison documentary “Scared Straight”: punitive, humiliating, and horrifying. Instead, he said the class was actually helpful. It took him a while to zero in on his trauma triggers and their roots, but he eventually figured them out.

“One was loud noises from the violence I was witnessing in my neighborhood, and another is the sound of people arguing,” he says. “That was mainly from my mom and her boyfriend. I’d seen them get into a lot of fights when I was younger.” Now when he finds himself getting mad, he’ll touch a piece of fabric, like his jeans, or some surface to ground himself, as the trauma training has taught him. “I’ll notice if it’s rough or smooth or hot or cold. It kind of brings you into the present moment.”

Liles and fellow researcher Blacker are currently seeking more grant money for the project and for a process that will allow them to analyze its results. They want to know whether the youth feel they benefited, and they’ll review the data to see whether participants had fewer altercations and penalties for disruptive behavior.

The curriculum has made a noticeable difference in how Nathaniel interacts in the world. “I used to think that when I do something to somebody, it only affects the victim,” he says. “But it actually affects a lot of people in the community as well. So now I think about how my actions affect everybody else.”

James has been out of detention since last October. He’s been living with his father, who’s now out of prison, and his stepmother, who he says has always been like a real mom to him, for which he is extremely grateful.

“She’s thrown birthday parties for me,” he says, “came to my graduation, and has my friends over all the time. She’s gone above and beyond what a mother would do.”

Meanwhile, he and his father are rebuilding their relationship day by day, a process that includes playing basketball and going to church together. Additional counseling that the probation department helped set up has also helped him deal with the jagged edges of his past, he says. The present no longer seems bleak, and he hopes to work together soon with his father in construction.

“All I want to do now is spend time with my family,” he says.

* PACEs Connection is a social network that recognizes the impact of a wide variety of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in shaping adult behavior and health, and that promotes trauma-informed and resilience-building practices and policies in all families, organizations, systems and communities.