“Recall Gavin Newsom” signs are popping up around California. At shopping centers and street protests, people fed up with the Democratic governor are asking voters to sign petitions. What began as a far-fetched effort by Republican activists has turned into a credible campaign attempting to throw Newsom out of office.

It’s hard to fathom in this deep blue state where Newsom clobbered his 2018 GOP opponent and, according to polls, remains popular with a strong majority of voters. But the coronavirus pandemic shifted California’s political landscape in two significant ways: It prompted a judge to give recall supporters more time to collect signatures — keeping their campaign alive long enough to gain momentum — and it led Newsom to enact a slew of new restrictions to curb the spread of the virus that have frustrated some Californians and energized recall backers.

The recall petition doesn’t say a word about the pandemic — it was written before the virus upended normal life. But it gained a surge of signatures after news broke in November that a maskless Newsom joined lobbyists for a dinner party at the posh French Laundry restaurant, even though he was telling Californians to mask up and avoid socializing.

The count has grown as the state’s unemployment system paid out billions to fraudsters, and its chaotic COVID vaccine distribution has left people scrambling for shots. With many schools, churches and businesses closed by Newsom’s stay-at-home orders, the recall that began as a conservative rebuke of his progressive policies has morphed into a referendum on his pandemic response.

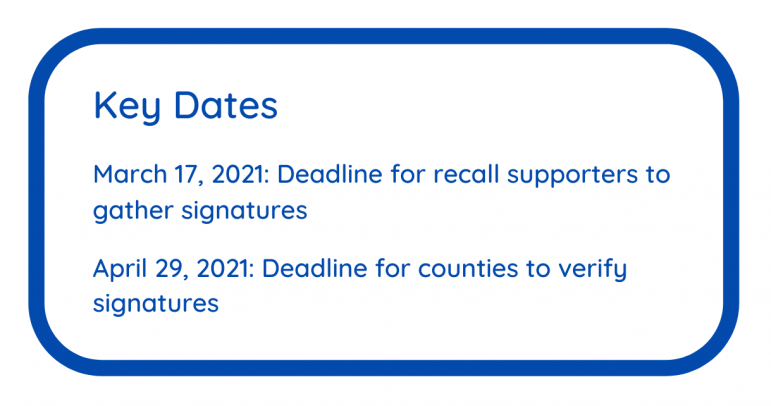

So is it election year again in California? Will you be asked to toss a governor just a year shy of the end of his term? It’s certainly possible. Recall supporters have now collected the signatures necessary to get it on the ballot. Here’s everything you need to know about recall elections in the Golden State.

How does a recall work anyway?

California is one of 19 states that allow voters to remove state officials before the end of their term. No reason is necessary — the only requirement to put a recall on the ballot is enough voter signatures. That number must be 12% of voters in the last election for the office, and must include voters in at least five counties. The magic number for Newsom’s would-be recallers: 1,495,709 valid signatures.

If the recall qualifies for the ballot:

- An election would be held later this year. A date depends on when state officials complete various preliminary steps. The recall campaign figures the election would be in August or September; analysts at the independent California Targetbook, an insiders’ guide to state politics, expect it would be in November or December.

- Voters would be asked two questions: Do they want to recall Newsom, yes or no? And, if more than 50% of voters say “yes,” who should replace him?

This is where things get strange. There’s no limit on the number of candidates who can run to replace an official on a recall ballot. And whoever gets the most votes wins — even without a majority. So it’s entirely possible that someone could be elected in a recall while winning less than half the votes. That’s what happened in 2003, when then-Gov. Gray Davis was recalled by 55% of voters. More than 100 people ran to replace him, carving up the votes and allowing action movie star Arnold Schwarzenegger to win with 48.6% support.© 2021CalMatters

What comes next?

Who’s behind the effort to throw Newsom out of office?

Republican activists have been trying to recall Newsom since shortly after he was inaugurated in January 2019. Five attempts failed to get enough signatures. But a sixth try, led by a retired sheriff’s deputy named Orrin Heatlie, gained momentum after a judge granted supporters extra time to collect signatures due to the stay-at-home order at the start of the pandemic.

Heatlie’s petition cites common conservative criticisms of California: high taxes, rampant homelessness, immigrant-friendly policies, and Newsom’s move to halt executions despite voters’ past support for the death penalty. Political consultants who worked on the 2003 recall of Gray Davis are mailing the petition to potential supporters, an unusual technique that reflects constraints of signature-gathering amid a pandemic.

Heatlie, a Republican who lives in Folsom, calls his campaign a nonpartisan effort and says it includes former Democrats who have lost faith in Newsom. “This is a movement that has brought people together throughout the state and unified people from all walks of life,” Heatlie said in an interview.

A few Silicon Valley tech executives who previously donated to Democrats now support the recall. But the campaign’s largest funders and most visible backers are Republicans. Supporters include wealthy businessmen and established GOP politicians, as well as far-right extremists who have peddled misinformation.

Newsom spokesman Dan Newman calls recall supporters “a strange mishmash of people who are motivated for different reasons….You’ve got some pro-Trump, anti-mask, anti-vaccine extremists, along with opportunistic and ambitious Republican politicians who would like to be governor.”

How are Democrats responding?

So far, Newsom has deflected reporters’ questions about the recall, saying simply that he’s focused on his job as governor — working to improve vaccine distribution, reopen schools and help small businesses.

But Democratic Party leaders are clearly worried that the recall campaign is gaining steam. Following the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol led by Trump loyalists, California Democrats held a press conference alleging links between the rioters and recall supporters, and calling the recall campaign a “California Coup.” Journalists immediately pointed out that a coup is an illegal seizure of power — while a recall is a democratic procedure enshrined in the California Constitution.

The California Democratic Party’s leader quickly walked back the “coup” comparison. But Democrats will likely continue tying the recall to Trump and the far right, given that the former president is deeply unpopular in California. That may be enough for Newsom to beat back the recall.

Disaffected Democrats would have to support the recall in droves to make it successful in a state where just 24% of voters are registered Republicans and the GOP hasn’t won a statewide contest since 2006.

Though they tend to vote for Democrats, roughly a quarter of California voters are not registered with either major party. So a key factor will be how much support Newsom hangs onto from liberal voters who don’t feel loyalty to him or the Democratic party.

Still, Democratic political consultant Garry South, who led the effort to fend off the 2003 Davis recall, has a warning: “Neither Newsom nor Democrats should ignore the recall, neglect to prepare for it or assume it will not make the ballot.”

Are recalls rare?

Attempts to recall politicians are extremely common in California, and growing more common nationwide. Successful recalls remain rare.

The only California governor ever recalled — and just the second nationwide — was Gray Davis. At the start of his second term, the Democrat faced the wrath of voters over his handling of the electricity crisis, a massive state deficit and an increase in vehicle license fees. Fueling the campaign: a $2 million donation from GOP Rep. Darrell Issa.

The real game-changer, of course, was the candidacy of Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Already famous worldwide, the actor and body-builder had been laying the groundwork for entering politics by sponsoring a ballot measure for after-school programs. He was a Republican with a bipartisan image, married to Maria Shriver, niece of Democratic former President John F. Kennedy. And he infused his campaign with celebrity: announcing his candidacy to host Jay Leno on “The Tonight Show”, dancing to “We’re Not Gonna Take It” at a rally with Twisted Sister, and inspiring plenty of parodies.

Since then, only one other gubernatorial recall has made the ballot in the U.S. — the 2012 attempt to throw Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker out of office. It failed.

This article first ran January 7, 2021 and was updated on April 26, 2021.