An evening online presentation for Earth Day used the Ron Howard documentary “Rebuilding Paradise” as the jumping off point for a discussion of what Nate Redinbo, the Civicspark Fellow at the city’s Planning and Building Department called “The intersection of fires and rising temperatures and drought.”

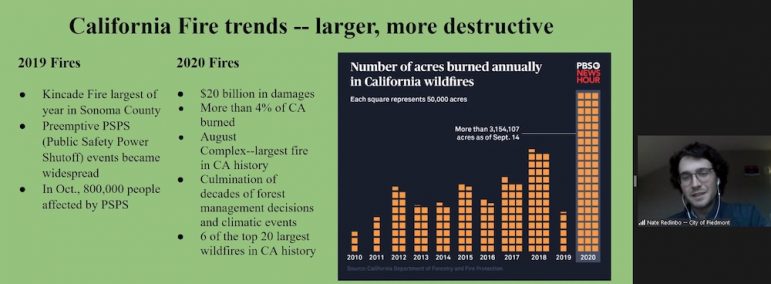

The town of Paradise burned to the ground in the 2018 Camp Fire, which overall killed 85 people and destroyed more than 18,000 buildings, including more than 13,000 homes, in the most destructive wildfire in California history.

The remote Northern California town is more than 160 miles away from Piedmont, but there are lessons to be learned from the disaster that devastated Paradise.

A panel of guest speakers — wildland fire scientist Sasha Berleman, incoming Piedmont Fire Chief David Brannigan, and Piedmont Fire Department Capt. Scott Barringer — discussed the realities of wildfires and why the community should be prepared for one here. Decades of fire suppression alongside new development have made wildfires increasingly common and harder to control in the state.

The ramifications extend far beyond the actual burn areas, as the Bay Area saw last summer when a toxic haze hung over the region from simultaneous fires far to the north.

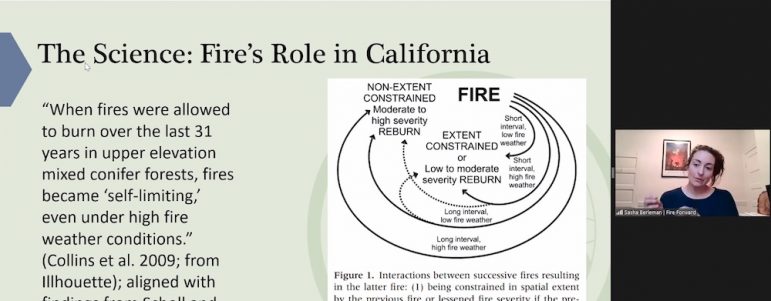

Berelman explained the history of fire in the Bay Area, how it was a valuable and necessary part of the ecosystem before Western settlement of the region, and how fire is being reintroduced through prescribed burns to maintain woodland and renew growth. Some species of trees and vegetation, in fact, depend on fire to clear areas and stimulate new growth of dormant cones and seeds that are only activated by heat, she said. Berleman, as director of the Audubon Canyon Ranch Fire Forward program, leads efforts to organize controlled burns as a means of fire management. Brannigan later noted that “The amount of carbons and toxins in a wildfire is many times what’s released in a controlled burn,” saying, “If you don’t take steps to manage it in a controlled way, the effect of smoke and carbon in the air is going to have a profound impact.”

Brannigan, who starts in his new duties on Monday, said that fire is oblivious to city boundaries. “Obviously we’re a dense city surrounded by an even more dense city,” he said, noting ongoing work to create a fuel break in the hills of Berkeley and Oakland that link to Piedmont. Barringer said that a “rigorous vegetation management plan” has been maintained since the 1991 Oakland hills fire.

Brannigan and Barringer both stressed the need for residents to be proactive ahead of time to reduce any fire threat and to react quickly and knowledgeably if the threat becomes reality. People “need to take responsibility for their own property,” Brannigan said, and yards and public spaces need to be managed in a way that lessens risk. Referring to the large area rebuilt after the 1991 Oakland fire, Brannigan said there have been “significant changes” to building codes and regulations, as well as evacuation plans to try and prevent or minimize a repeat disaster.

Piedmont is working with Oakland, Berkeley and state agency Cal Fire to share and coordinate with real time information for planning, training and providing alerts to the public during a potential or actual wildfire. Residents, too, need to be prepared, they said, and not just those living in or near heavily wooded areas.

Brannigan called it “Everybody’s problem,” saying that “all Piedmont is at risk” in the event of a wind-driven fire.

Barringer noted that the department has resources online ranging from vegetation management to evacuation. “I highly urge you to educate yourself,” he said, adding that the department is available 24/7 if residents want to call with questions. “The whole system works better when you’re on board with it,” he said, adding that the new reality in California is that “Fire season is pretty much 24/7/365.”

“Keep evacuation boxes ready to go,” Barringer said. “If you don’t get out in the first five minutes you’re not going to leave.”