“Popular Monitress” isn’t exactly a solo venture. Jon Leidecker, who has been releasing music under the pseudonym “Wobbly” since 1990, has captured communion with the machine.

The San Francisco-based multimedia artist, known for his involvement in legendary experimental group Negativland and the Thurston Moore Ensemble, released “Popular Monitress” in February, a follow-up to his 2019 release, “Monitress.”

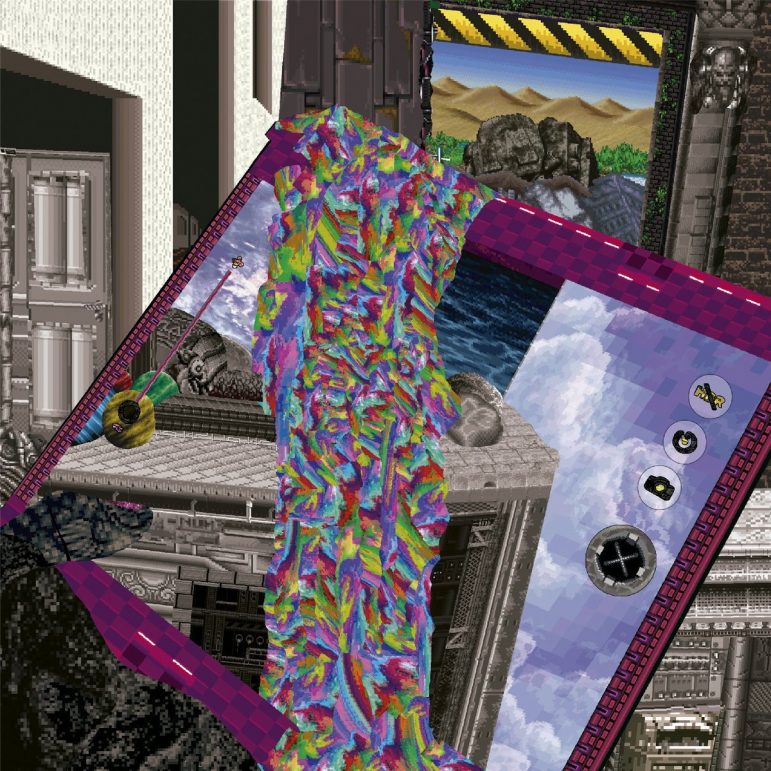

Both albums toy with the concept of machine listening, and its warped replication of human tuning. Using several mobile phones equipped with synth software and a 50-year-old “protoplasmic” processing code, Leidecker has woven man and machine into playful polyphony.

In the following interview, Leidecker reveals the rationale behind his experimental approach, the art of socializing in solitude and why older forms of technology should not be dismissed.

Firstly, how is isolation in San Francisco treating you?

Leidecker: My neighborhood between the Mission and Noe Valley reverted to a quasi-village consciousness I never thought I’d see in San Francisco, people telecommuting from their front steps and waving at passersby. Less once it got cold, but I’m grateful for random phone calls suddenly being OK again. Food tastes amazing. Nothing’s easy, but some things are clearer. There will be many good things to remember.

How did your approach differ in creating ‘Popular Monitress’ vs. ‘Monitress’? What is the relationship between the two albums?

Leidecker: “Monitress” started as a live improvised piece — different every time, but still making the same point. So both albums — all different tracks, but again, one piece, all built around mobile phones, and machine listening. What these phones are, and how they listen to us. In performance, I make sounds and melodies on one of them, and then send that sound to another four or five, all of which are running code that detects and tries to play the melody in what they’re hearing. Just like speech recognition often gets it pretty wrong, the melodies they make are fascinatingly weird, and individual — they really do sound like a bunch of voices all trying to sing in unison. In spite of, or because of those errors, it kind of gets at the heart of what humans instinctively recognize as music. It gets weirdly emotional.

Improvisation is key to the process — if you’re hearing the machines sing along to your notes even as you play them, you quickly close the circle with that code, and begin responding to what you hear — especially when they hear things you don’t expect. There’s a lot of pleasure in that blurring between the initial sound and the response, that means the music’s really working. So the first album, “Monitress,” was more simply about that blend, where you can’t always make out the human input — the more abstract it gets, the more fun it is for me personally. On the second one, I wrote some fairly straightforward tunes, and in two instances even played them on a shamelessly acoustic grand piano. It’s an easier way into hearing how the machines are listening. And that’s really the central thing to get out of any version of “Monitress” — to be able to hear exactly how those machines are listening.

Do you lead with concept in your work, or is it more of an experimental process?

Leidecker: Having fun just playing; the music always leads. But it’s not a surprise when the result naturally leads you to the concept. Since high school, I’ve always liked playing along to records, as well as playing more than one at once, sampling them and so on. That doesn’t even seem all that experimental these days, but even back then it felt less like a conceptual practice than a totally social way of making music while you happened to be alone, a way to keep music feeling social, even while listening to it alone. And I’ve always liked that kind of meta-music that seems to invite you into how it was made, the ones that really open up questions of structure. For me, the more playful the music is — the more likely it is to be able to model those larger concepts.

Which is why I tried to keep the concept for “Monitress” so loose! There’s nothing new about the core tech I’m using — the code for these pitch trackers goes back 50 years. They’re still too chaotic for many to use if you’re the kind of musician who needs their tools to do exactly as they’re told. But the point here is, that when we talk about technology, our focus on the coming new makes us completely lose sight of everything that’s already possible.

They really do sound like a bunch of voices all trying to sing in unison. In spite of, or because of those errors, it kind of gets at the heart of what humans instinctively recognize as music. It gets weirdly emotional.”

JON LEIDECKER, A.K.A. WOBBLY, ON HIS EXPERIMENTS WITH MACHINE-LISTENING AND MELODY

For years, we had that buzzing warning that AI deep fakes were coming, and all the videos you’d see would be compelling, but still awkward enough to reassure yourself your reality detectors were still working. And then in mid-2019, someone uploaded a video of Nancy Pelosi VariSped down 15%, and half the country was convinced she’d had an aneurysm. It’s not about new tech; it’s about our relationships with all the recent tech that’s already gone invisible. So re-using this 50-year-old protoplasmic code for my album seemed the best way to get at these issues of machine creativity and collaboration in a much clearer and audible way than a lot of the “made with AI” music I’ve been hearing.

I mean, it’s worth rolling it into the music, the things that happen now, that these trackers are now just sitting on my phone. They’re capable of singing along with birds when I’m on a hike. Birds really hate it when you play them recordings of other birds, but they love it when they hear these things.

What inspired you to pursue solo ventures as a musician?

Leidecker: The solo ventures have kind of always been happening. But I release fewer of them, because they’re harder to ever call done — to finish it, you have to stop playing it, which can feel pretty wrong. You have to put on a different hat to turn it into an artifact. Collaborations often seem to finish themselves, what you can play live with others is instantaneously that much more complex and closer to being done. And as much fun as “Monitress” is solo, those pitch tracking apps sound even wilder live when pointed at acoustic instrumentalists — the blend is really confusingly beautiful. I have three recently released duo albums, with Zeena Parkins on harp, Kanoko Nishi on koto and Tania Chen on piano playing Morton Feldman, all definitely connected to these solo albums.

In fact, the one thing my solo stuff usually seems to have in common, from the older sampling collage to the current machine-listening music, is that it’s never really supposed to come off like a solo — more like a whole bunch of relationships and a whole lot of listening. Even if they aren’t always listening to each other.

Who are some of your more recent sonic influences?

Leidecker: There’s a long list of pioneers of algorithmic and generative music in the liner notes for “Popular Monitress.” There’s generally more in the way of kick drums on my album than in the pieces I mention, but I’ve been listening to that stuff pretty obsessively — that’s all being pretty honest with me. Especially, still, Roland Kayn — I recently went on a pilgrimage to Leo Kupper’s studio in Brussels to see his hand-built GAME synthesizer, running the length of his basement, and which Kayn famously used for his ’70s box sets. He demonstrated one module, which could be set to send triggers that randomly fired anywhere up to a week apart. “So you need one week minimum of listening to perceive the form of this music,” he said. That got at something wonderful for anyone trying to evoke the kind of long-term decision-making we’ll need to survive.

Which contemporary artists excite you right now?

Leidecker: Anyone under 10. I don’t have kids, but my friends’ kids all have that kind of creativity that makes me realize there’s no choice but to keep working.

What’s next for you? Any new projects on the horizon, or ideas you’d like to engage with?

Leidecker: This year was difficult for everyone, but I was lucky. There’s an album coming out with my old friends Jay Lesser and Blevin Blectum, the second album by our band Sagan, about the future of space travel. There’s a vinyl LP coming out with my friend, the instrument designer and composer Cheryl E. Leonard that we largely recorded outdoors. There are some great recordings with the Thurston Moore Group, capturing a lot of the long pieces we recorded in the studio after they broke themselves open on the road. Keith Fullerton Whitman and I playing Luc Ferrari in NYC; I sure hope that comes out. Negativland and Sue-C are playing an extended bona-fide livestream collaboration for Ann Arbor Film Festival, which will be very much about the media we’re using to play. Me and my fellow technology-obsessed friend, Jennifer Walshe, have some more radio plays to make. And there’s this uncertain album of things that almost seem like they’re songs.

* Jon Leidecker’s last two albums as Wobbly can be found on Bandcamp at https://hausumountain.bandcamp.com/. Watch Negativland and Sue-C at the Ann Arbor Film Festival at noon March 28 at https://www.aafilmfest.org/59-in-the-screen.