No one can see the future. But former archaeologist Dan Rael and software developer Howard Burrows, both of Oakland, came pretty close when they developed CatalogIt, a mobile app they designed to help private collectors document and catalog their collections.

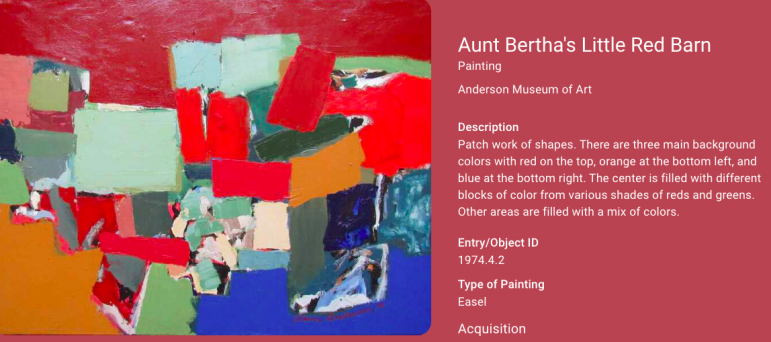

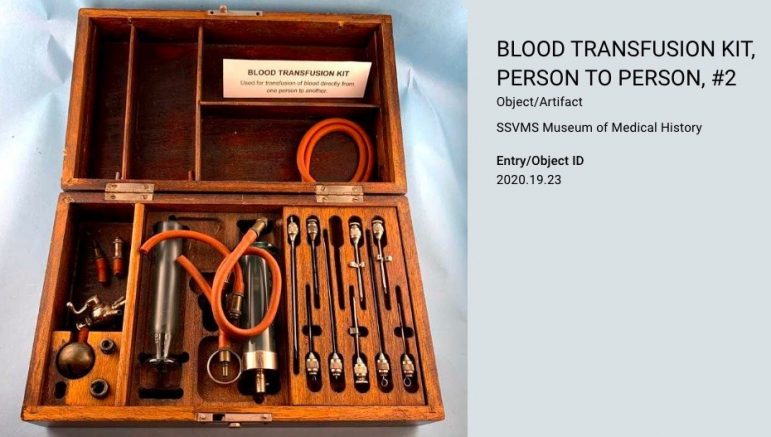

Today, thousands of museums, organizations and private collectors around the world are using the app, and some are posting pieces of their collections in the publicly accessible CatalogIt HUB, giving sheltered-in-place, museum-starved art lovers a new place to browse for art, photos and more.

HUB visitors can spend hours clicking through thousands of entries, or search across the entire HUB database for a specific type of object or topic. More than 100 Catalogit users, including the Berkeley Historical Society, the National Black Doll Museum of History & Culture in Massachusetts and the Basque Museum and Cultural Center in Idaho, have made their collections publicly available online.

It all started in 2015 with Rael, who’d been collecting Native American baskets and art for years. Burrows was always after him to document his collection, so Rael did what many collectors do: He considered building a giant spreadsheet.

Burrows discouraged the spreadsheet idea. “There’s got to be a program out there,” Rael recalls him saying.

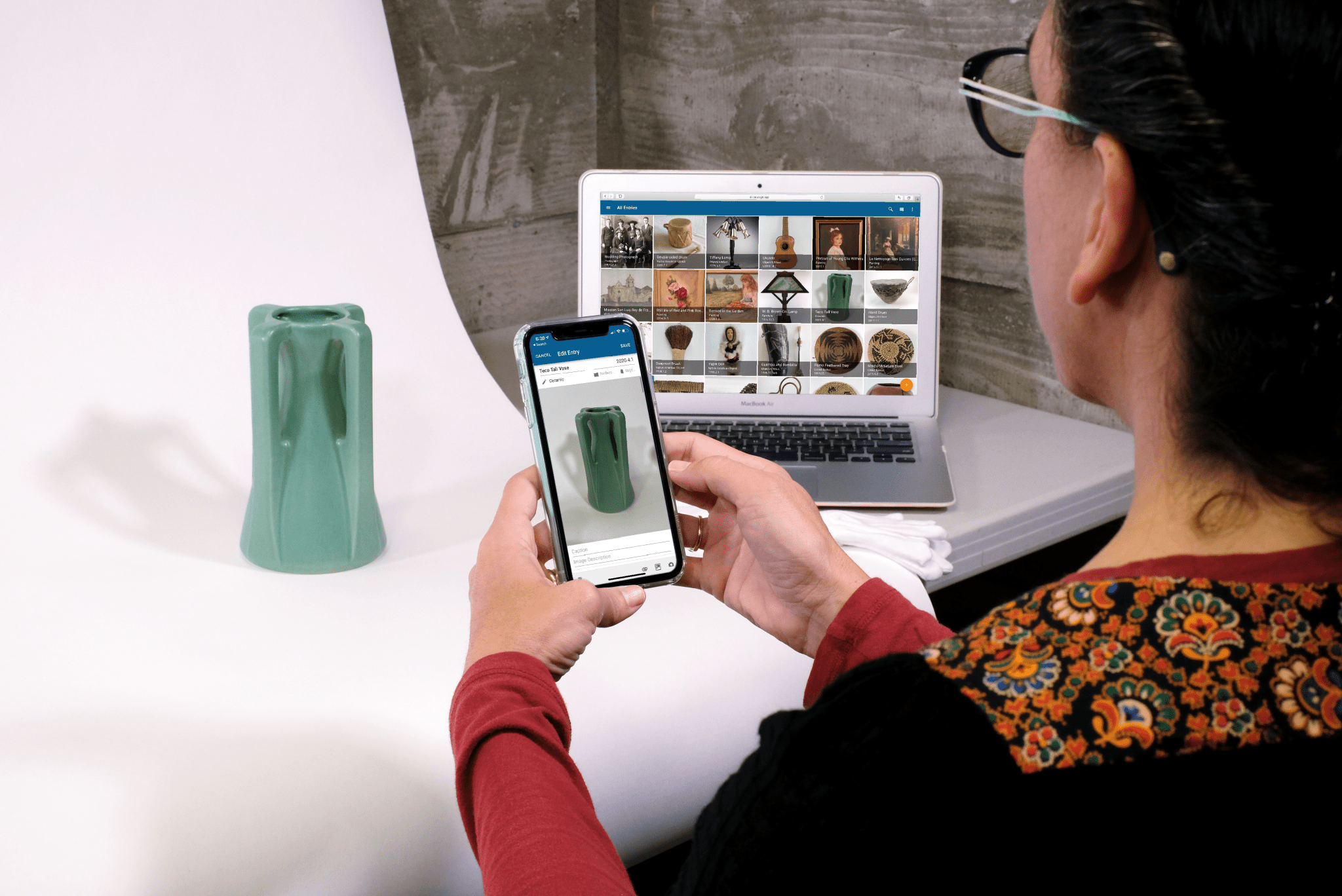

Rael and Burrows looked around, but the closest they came was bar code technology – not a fit for a private collector, or for one-of-a-kind artworks created long before bar codes existed. So, Burrows developed a smartphone app and Rael started uploading his collection to a cloud-based database and typing in details about each object. It was much easier than a spreadsheet, and Rael could access his collection any time from his phone. CatalogIt was born.

Rael and Burrows started making CatalogIt available to private collectors in 2017, and soon after they met Joy Tahan Ruddell, a longtime museum registrar and consultant who had managed museum collections for years. She was impressed with how easy and intuitive CatalogIt was to use, and saw the need it could fill in museums.

Museums are really behind in technology, and they’re working to catch up, she says. “The notion of being able to use your handheld device to catalog your collection was really groundbreaking to me.”

Rael, Burrows, and Tahan Ruddell teamed up to expand CatalogIt beyond private collectors and into the museum world. Today, more than 1,000 museums and organizations and nearly 3,000 private collectors around the world have CatalogIt accounts. They can opt to publish to the CatalogIt HUB, or keep their collections private.

Museum and gallery employees and volunteers who had struggled with complicated or archaic museum software have found CatalogIt easy and fast to learn and use.

Lind Higgins, resource center director for the Concord Historical Society, says the organization has thousands of photos, documents and artifacts that were previously cataloged using a different technology. They are now using CatalogIt, and volunteers have found the app is very intuitive to use, she says.

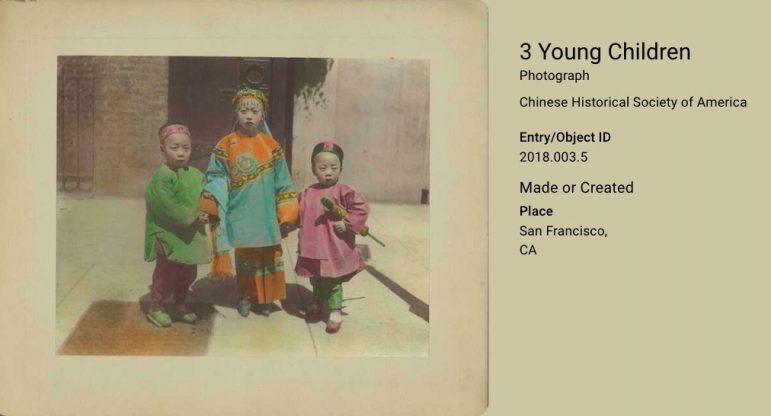

Private collectors make up the largest number of CatalogIt users, and many keep their collections private. The app is flexible — people use it to catalog family photos, letters, paintings, sculpture and more. The app also has built in classifications, so if you upload a photo for example, you will be prompted to provide the subject, where and when the photo was taken and what kind of photo it is. Is it a digital photo or a gelatin print? Or perhaps it’s a daguerreotype?

It’s satisfying work to catalog and describe your stuff.

Tahan Ruddell recently received family photos, letters and documents that she has cataloged. She’s been able to indicate who’s in each photo, and who wrote the letters. Once her work is done, she can search on an individual, say, her grandmother, and every photo that her grandmother is in, and every letter her grandmother wrote, will appear.

“Being able to tie that family history together has been really great for me,” she says.