Tami Roncskevitz has attended two Zoom memorials for her daughter, Sarah, a 32-year-old emergency room social worker who died of covid on May 30. But she longs to gather Sarah’s friends and family together in one place so they can embrace and mourn together.

“It just isn’t the same,” said Roncskevitz. “You feel like your grieving is not complete.”

With more than 520,000 in the nation lost to the coronavirus, the United States has millions of people like Roncskevitz whose grief is compounded because families — which, in her case, includes Sarah’s fiancé and two young children — have been unable to publicly celebrate the lost lives with in-person memorials.

Honolulu artist Taiji Terasaki is stepping into that breach with a project to commemorate fallen health care workers.

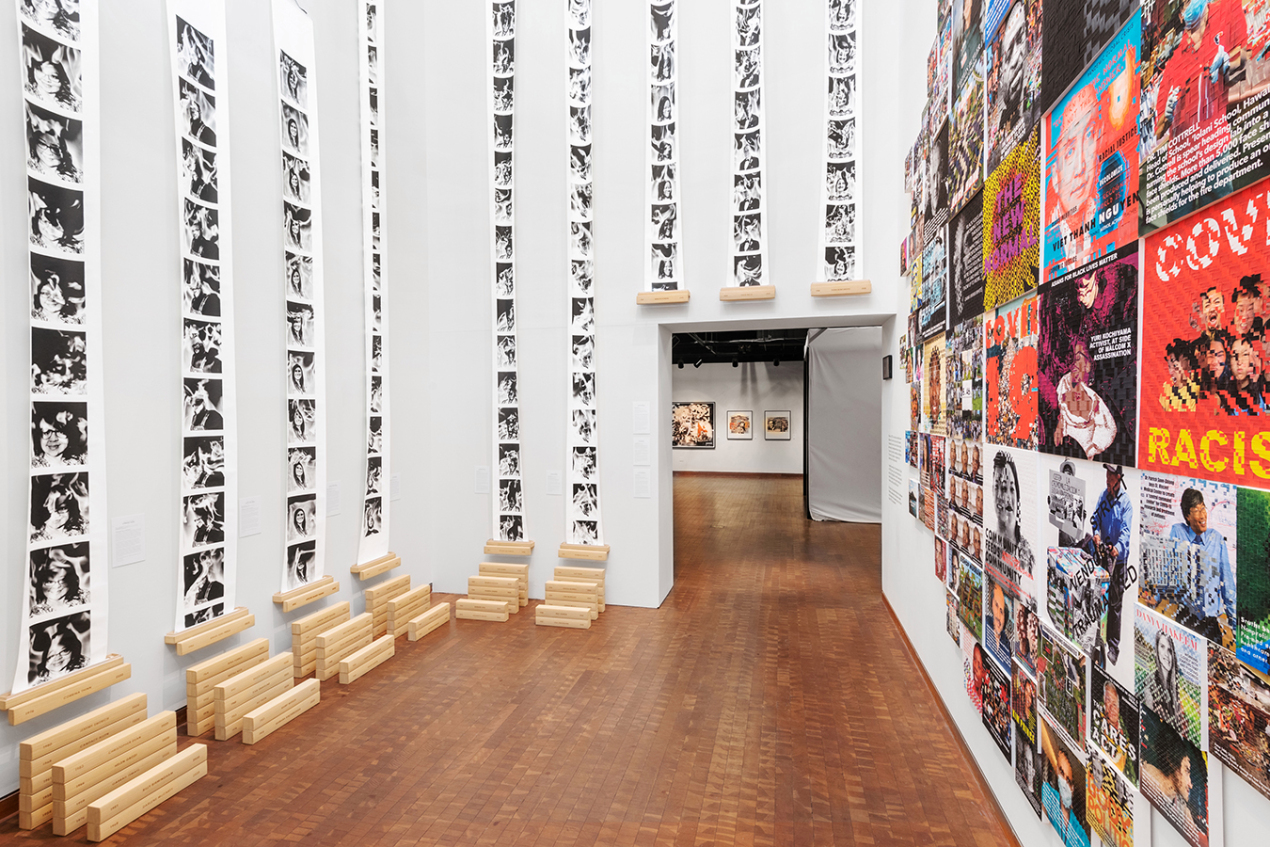

Terasaki first projects an image of the deceased onto a screen of mist droplets. He then photographs several dynamic, ephemeral portraits of the mist projections, and then prints these photos onto a long scroll. The effect is a mashup of traditional kakejiku, or Japanese hanging scrolls, and a gigantic filmstrip.

Each scroll is then placed in an inscribed wooden box and can be unfurled for display.

The effect is bittersweet, said 59-year-old Roncskevitz, who lives in Benicia, California, and saw the images online.

“I can see her smiling face, but I can also see it evaporating in that picture,” she said. “For me, I feel like it’s representative of Sarah’s body dissipating, and her spirit moving forward.”

So far, Terasaki has created 15 mist portraits for health care workers, who include radiologists, janitors and nurses. The scrolls can be unfurled up to 20 feet and are currently installed in the Japanese American National Museum in downtown Los Angeles, which is closed due to covid restrictions. But the exhibit, called “Transcendients: Memorial to Healthcare Workers,” will make its world debut virtually on March 13, along with other artwork Terasaki has made to commemorate pandemic heroes. “Transcendient” is Terasaki’s neologism from “transcendent” and “transient”; it’s a concept he has used in past exhibits on immigration, the U.S. migrant border crisis and the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

At the beginning of the pandemic, Terasaki passed his lockdown time cutting photographs and weaving them back together to create pixelated, screen-like images of people who had helped others during the pandemic. He posted these works on Instagram every day for 100 days.

As deaths mounted, he decided to create memorials and came across “Lost on the Frontline,” a collaborative reporting project between KHN and The Guardian. The series features short profiles of health care workers who have died of covid, as well as investigative stories about the lack of personal protective equipment many workers endured as they showed up for work during the pandemic.

“Who’s sacrificing the most? It’s these health care workers who are out there risking their lives,” said Terasaki.

Terasaki reached out to KHN to see if he could add to the collaboration with the memorial scrolls, and then set out to contact the families featured in Lost on the Frontline.

Expanding the project to incorporate art is going to widen the project’s reach, said Christina Jewett, KHN’s lead investigative reporter for Lost on the Frontline. To date, the team has identified more than 3,500 health care worker deaths caused by covid and is the most comprehensive database to date, as states have different requirements about recording and reporting these deaths.

Helena Cawley contributed a portrait of her father to Terasaki’s project to keep his memory alive. She recalled receiving the news that her father had unexpectedly died of covid. Cawley let out a primal scream and dropped to the floor, sobbing.

This was March 30, back when covid tests were scarce, hospitals were scrambling to obtain ventilators and masks, and the U.S. had just passed 3,000 deaths from the disease.

Cawley’s father, 74-year-old hospital radiologist David Wolin, was the first person Cawley knew who tested positive for the virus. A month later, Wolin’s wife, Susan, Cawley’s stepmother, also succumbed to the disease.

Because New York City was under stay-at-home orders, no visitors came to comfort Cawley’s grieving family; no one could relieve them from the pressures of child care or chores as a friend might have done before the pandemic. Cawley recalled that about one hour after learning her father had died, she was back in the kitchen, blinking back tears as she prepared lunch for her two young children.

Cawley leaned on her husband for support as she went through the logistics of grief throughout 2020, which included clearing out her father and stepmother’s apartment and lake house. She now wears a ring her father received as a gift, and sometimes visits his grave or sits on a park bench that the Brooklyn Hospital Center named in his memory. And she’s grateful for opportunities to keep his name and image circulating, especially since her family has yet to organize an in-person memorial.

“It’s so great to have people remember him and think of him and want to honor him,” said 41-year-old Cawley. “I love having his name out there and letting people know who he was.”

Terasaki, 62, has explored death, grieving and rituals in past work. The 2017 performance art exhibit “Feeding the Immortals” invited the public to bring food that reminded them of a deceased loved one, and to speak about the person and place the food on an altar.

The work was a reaction to the 2016 death of his father, Paul Terasaki, a pioneering organ-transplant scientist who had been detained as a child with his family in an internment camp in Arizona during World War II.

After his father died, Terasaki struggled to connect with the Christian funeral services organized to remember him and decided to create his own ritual. Even before the pandemic, Terasaki felt that American culture weakly commemorated its dead. Now that the pandemic has put a chill on community death rituals, the lack is even more glaring.

Terasaki is sending a 7-foot scroll to each family participating in the art project, in the hope they might unfurl and display it once a year on the death anniversary. Terasaki also hopes to create small community memorials throughout the U.S.

“What’s really missing in our culture is the ritual and ceremony — to really get quiet and reflect and just experience the silence,” he said. “We need to find a space of reverence for the lost.”