The narrative that “Asians are good at math” is pervasive in the United States. Young children are aware of it. College students’ academic performance can be affected by it.

On the surface, the “Asians are good at math” narrative sounds like a compliment. After all, what’s wrong with saying that someone is good at something? But as I have explain in an article, there are two problems. First, the narrative is false. Second, it is racist. And in the midst of an upsurge in violent attacks against people identified as Asian, it’s worth remembering that the core of anti-Asian racism has always been dehumanization.

I’m an experienced teacher and researcher of STEM education. Research tells us that racism is a part of students’ classroom experiences in these subjects.

If we don’t understand how racism works — even in supposedly “neutral” areas like STEM — we might unintentionally recycle racist ideas.

Debunking the myth

As with many racial stereotypes, people are genuinely curious whether the “Asians are good at math” narrative could be true. There are videos on YouTube with several million views asking that question.

Don’t test scores prove the narrative? In fact, they don’t. On international exams, it’s true that Asian countries are among the top performers in math. But it’s also true that other Asian nations rank 38th, 46th, 59th and 63rd. Interestingly, those top performers also lead in reading — but there isn’t a narrative that “Asians are good at literature.”

Domestically, it’s the same story. Research shows considerable variation in mathematical performance among different Asian ethnic groups in the U.S. If all Asian people were innately gifted in math, we shouldn’t see this kind of variation.

A better explanation has to do with education policy and federal immigration laws. Countries that invest in teacher education and high-quality curriculum do better on international tests. In the U.S., the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Actgave preference to STEM professionals from Asia. That policy affected my own parents, who were able to immigrate to the U.S. under that law, not because South Asian people are naturally good doctors.

‘Mongoloid’ to ‘model minority’

So if it’s not true, why do we say it?

Today, Asians are often seen as the “model minority” — hardworking, academically talented and professionally successful — but it wasn’t always that way.

In the 18th century, Asian people were classified as “mongoloids,” a racist term based on the pseudoscience of craniometry. Whereas “caucasoids” (white people) were deemed full human beings with superior intellect, all people of color were considered underevolved.

From the late 19th century, a new image of Asian people was born: national threat. Chinese immigrants were seen as an economic threat to white American workers, and Japan became a military threat during World War II.

Asian people in the U.S. continue to experience racism even today. In fact, the “model minority” idea has always been a way to pit Asian people against supposedly “nonmodel” groups — in other words, non-Asians of color.

The implication is: If Asians can do it, why can’t you?

People, not robots

Even though the “Asians are good at math” narrative is false, it still has a real impact on people’s lives. Like the “model minority” myth, it falsely positions non-Asians of color as mathematically inferior. It can also be a source of pressure for Asian students. But the real impact of the “Asians are good at math” narrative goes deeper.

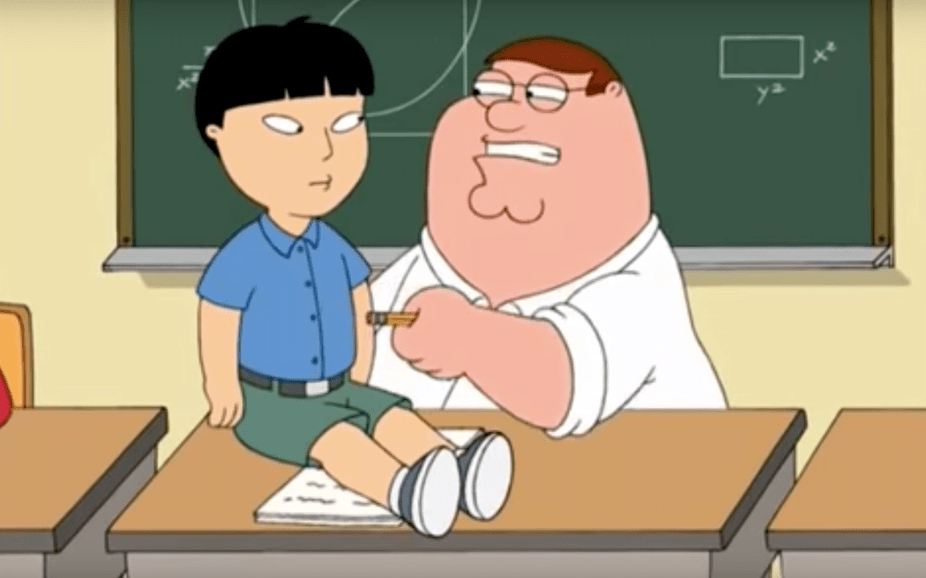

Take, for example, a scene from an episode of the long-running adult cartoon “Family Guy.”

The main character, Peter, is reminiscing about taking a math exam. As the shot pans over other students, each take out a calculator from their pocket. Peter pulls out a boy with Asian features, prods him with a pencil and says: “Do math!”

This might seem funny at first, but the underlying message is clear: Asian people aren’t seen as human beings; they are calculating machines. Asians are literally objectified, seen as capable of doing things at a speed and scale that “normal” people can’t do. In other words, they are dehumanized.

Calculators are capable of only procedural tasks, not creativity. For Asian people, this implies that while they can succeed in the technical STEM subjects, the humanities and creative arts aren’t for them.

Part of what’s going on has to do with how society understands “good at math.” Math is widely considered to be among the hardest subjects to learn. Those that can do it are often seen as “nerds.” Movies about mathematicians like “A Beautiful Mind” and “The Imitation Game” usually portray them as antisocial. Mathematicians might be considered brilliant, but they aren’t seen as “normal.”

Usually we think about dehumanization in terms of intellectual deficit. For example, Americans in the 21st century still associate African American people with apes, a racist trope. What’s happening with Asian people is different but still harmful. They become hyperintelligent robots.

Resisting the narrative

We all can play a role in resisting this false narrative.

Teachers can help by monitoring the kinds of learning opportunities they give Asian students. Do they treat them like calculators — only giving them rote procedural tasks — or do Asian students get to show their creativity and to present ideas in front of the class? To help teachers track biases, my research team has developed a free web app called EQUIP.

Most people easily recognize overtly racist behavior and language. But I believe we also need to learn how to spot racism in its more subtle forms. The next time you hear someone say “Asians are good at math,” don’t hear it as a joke — hear it as racism.

* Niral Shah does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This story originally appeared in The Conversation.