As violence against Asian Americans surges across the country, education leaders in California strongly condemned the racist attacks and underscored schools’ crucial roles in combating xenophobia and teaching tolerance.

While racism against Asian Americans has always existed, especially in California, the recent increase began a year ago, as former President Donald Trump falsely blamed the Covid-19 epidemic on China. In the past few weeks, Asian Americans have been attacked in Oakland, San Francisco and other cities, and last Tuesday, a man in Georgia killed eight people, six of them Asian women. Police are still investigating.

Since the shutdown a year ago, nearly 3,800 Asian Americans have reported being victims of racist physical or verbal attacks, according to Stop AAPI Hate, a group formed last year to draw awareness to the issue.

Other data signal a worsening situation. Anti-Asian hate crime increased in major cities from 2019 to 2020 while overall hate crime dropped, according to police reports collected by the Center for the Study of Hate & Extremism at Cal State San Bernardino.

A Pew Research Center survey in July 2020 found more anti-Asian and anti-Black sentiment than before the pandemic. Six in 10 Asian adults say it is more common for people to express racist or racially insensitive views about people who are Asian than it was before the coronavirus outbreak compared to 4-in-10 white, Black and Hispanic adults. Forty-five percent of Black adults also said it was more common to hear racist comments about Blacks since the pandemic.

“The pandemic has brought a lot of pain and suffering for many, and, with it, conspiracy theories scapegoating the Asian community for the Covid-19 pandemic,” said Dr. Vincent Matthews, superintendent of San Francisco Unified. “We have to stand together against violence perpetrated against any member of our community.”

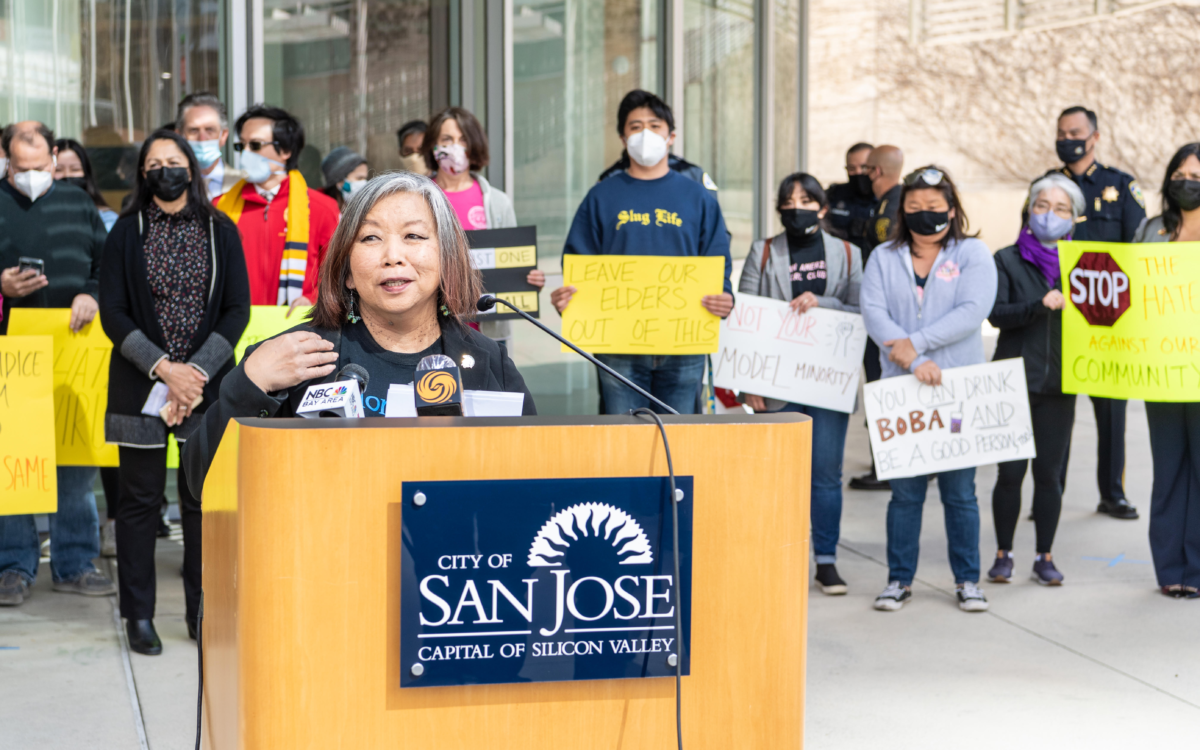

Across the state, college and district officials, students, faculty and community advocates have condemned the attacks, racism and discrimination targeted at those who are foreign-born, as well as Asian Americans.

“I am particularly concerned because the shootings in Georgia come in the wake of hateful and utterly unprovoked attacks against Asians and Asian Americans in the Bay Area and beyond,” UC Chancellor Carol Christ said in a campus message last Wednesday. “In fact, earlier this week two women of Asian descent were subject to abuse and harassment while waiting in line at the University Village food pantry.”

The incident involved a verbal disagreement March 15 between an adult man and two Asian women in University Village. However, no one involved requested a police report, according to Lt. Sabrina Reich of the UC Berkeley Police Department.

Of the nearly 3,795 incidents reported to Stop AAPI Hate between March 19, 2020, and Feb. 28, 16% occurred to people between the ages of 18 and 25. About 4.5% of the incidents occurred in a school setting and 2.5% happened in a university. Nearly 44.6% of these incidents occurred in California.

Larger K-12 districts around the state, most of which remain in distance learning, have not reported an increase in hate crimes or anti-Asian bullying in the past few months. But several noted that those incidents are often underreported and might well be happening under the radar.

Meanwhile, superintendents widely condemned the attacks and offered support to Asian American students, families and the community.

Although most University of California and Cal State campuses say they haven’t received any formal reports of incidents targeting students, faculty or staff of Asian descent, many are offering programs to confront anti-Asian racism and xenophobia.

Stanislaus State, for example, will host a Zoom panel discussion in May with experts discussing racism, xenophobia and strategies to drive social change. Cal State Los Angeles held a similar discussion earlier this month with U.S. Rep. Judy Chu.

Although incidents may not have occurred on campuses, Asian and Asian American students and faculty say they still experience discrimination and racism.

“These anti-Black, anti-Asian, anti-Jewish, anti-LGBTQ, sexist remarks, they still happen on campus,” said Kathleen Wong(Lau), chief diversity officer at San Jose State. “We regularly receive complaints coming into our office of things that happen in chat, or on Zoom.”

Wong(Lau) said what’s more typical is the incidents that happen outside the university where students work or hang out. For example, graffiti written on Vietnamese restaurants or shops in the San Jose area or people spat on or attacked while walking Bay Area neighborhoods.

But there is still more colleges and universities can do.

“The role of colleges and universities is huge,” said Su Jin Gatlin Jez, executive director of California Competes, a nonprofit focused on improving college access and outcomes. “The universities can hold firm in supporting safe and inclusive environments on their campuses. No students should worry about getting harassed on the way to class or in class.”

Gatlin Jez, who is a Bay Area native, was raised by her Black father and Korean mother. She recently wrote about her experience confronting bias, racism and discrimination.

“During last summer’s heightened racial unrest, I was scared to take walks for fear of being caught alone and vulnerable by white supremacists,” she wrote. “I think back over my own experiences of anti-Asian racism. They are not violent, but they matter. I remember being a child, watching people react to my mother’s foreign accent. Put-downs from store clerks and mistreatment from bank mortgage officers won’t leave you bloodied, but we know those experiences have nontrivial impacts on someone’s ability to thrive.”

Gatlin Jez warned that policy researchers and academics often talk about Asian Californians’ “strong educational and socioeconomic” success. But they shouldn’t forget, “the pain and suffering experienced as individuals in a society structured over centuries to bolster white success at the expense of all people of color.”

One way colleges and universities could help curb racism and discrimination on their campuses is to create systems for students and staff to report discrimination, Gatlin Jez said. Unfortunately across California’s colleges, these reporting structures vary in where they’re located, who’s in charge, and the actions they can take, if they exist, she said.

At San Jose State, Wong(Lau) advised that students and staff should report incidents to someone they’re comfortable with, such as department chairs, the student ombudsman, or the campus diversity and inclusion office.

“Even if a student says they don’t want to move forward, we provide counseling, tutoring or recommendations to move someone to a different class, for example,” she said.

In the K-12 schools, the recent attacks come amid the approval of an ethnic studies curriculum for California schools, which advocates hope will lead to more tolerance and inclusion on campuses.

But ethnic studies classes alone will not solve the problem of racism against Asian Americans and other groups, said Dr. Jun Xing, chair of the Asian and Asian American Studies Department at Cal State L.A. and executive director of the Asian and Asian American Institute.

Ethnic studies should be mandatory, and anti-racist curriculum should be woven into all subjects, in all grades, to have a meaningful impact, he said. In addition, the curriculum should flow cohesively between K-12 schools, community colleges and universities, and districts should do a better job of collecting data about racist incidents on campus.

“In order for us to get to the root of the problem — understanding the stereotypes, the racism, the discrimination, the history — we need to start educating students from the very beginning, not wait until they’re in college,” he said.

California’s fraught history of racism and violence against Asian Americans, beginning with the treatment of Chinese laborers during the Gold Rush, makes the issue even more urgent, Xing said. California’s Asian American and Pacific Islander population has been steadily growing and now makes up 15% of the overall population, according to the Public Policy Institute of California. Among the umbrella of “Asian American” is a diverse array of subgroups, including Indians, Hmongs, Vietnamese, Koreans, Japanese, Samoans, Filipinos and Chinese.

“We can’t overlook the long history of discrimination and racism in this state, but we can take ownership of it and learn from our mistakes,” Xing said. “In that way, California can really take a leadership role.”

Vice President Kamala Harris, whose mother was Indian American, also offered her support for the Asian American community as she and President Joe Biden visited Atlanta on Friday to offer solace to the victims’ families. “Everyone has the right to go to work, to go to school, to walk down the street and be safe. To be recognized as an American — not as the other — but as us. A harm against any one of us is a harm against all of us,” Harris said.

With campuses mostly closed due to the coronavirus pandemic, Guan Liu, a political science and history sophomore at San Diego State, who immigrated to California as a 1-year-old with his parents from China, said he applauds the efforts to expand ethnic studies in K-12 and across the CSU system.

“But the root of the issue can’t be solved through a single course,” he said. “Our community has always been that invisible minority, and we haven’t spoken up about these issues … but we do need to speak, and it’s all of our responsibilities — those in the community and our allies.”

Jone Ho of Sonoma County warns her 6-year-old daughter to be on guard for bullies and protect her 3-year-old sister. “We are Chinese and our skin is different from theirs. It is very likely that you may get attacked. So you must learn to protect yourself.”

Meghann Seril, a 3rd-grade teacher at a Spanish-Mandarin-English immersion school in Venice in Los Angeles County, tries to incorporate lessons about diversity and tolerance throughout the school year. When events like the Atlanta murders happen, she encourages her students to talk about it.

“I felt it was important for them to process what they were hearing,” she said. “It requires a lot of reflection, but I was proud that my students wanted to engage and talk about it honestly. I feel that they ‘get it,’ and understand that we have to treat all people with respect.”

As an Asian American teacher, Seril said she feels a personal imperative to educate her students about diversity and tolerance.

“These issues only get more complex as we get older,” she said. “We have to show kids that our differences are something to be celebrated. It’s never too early to start that conversation.”

Joining other superintendents who have issued statements in recent days, Oakland Unified Superintendent Kyla Johnson-Trammell wrote in a letter to the community, “THIS NEEDS TO STOP.”

The district is offering support groups, storytelling sessions, anti-racism workshops, lesson plans, guidelines for reporting racist incidents and other measures intended to promote inclusion and tolerance. The district also has an Office of Equity, with an ongoing initiative focusing on the unique needs of Asian American and Pacific Islander students, who make up 12% of student body.

Los Angeles Unified also has an Educational Equity and Compliance Office that promotes anti-racist and anti-bullying lesson plans and curriculum. Asian and Pacific Islander students make up about 5% of the district’s overall enrollment.

“We do not tolerate bullying, hazing or any behavior that infringes on the safety or well-being of students or employees or interferes with the teaching and learning environment,” said a district spokeswoman.

EdSource staffer Yuxuan Xie contributed to this report.