As more California school districts reopen campuses, many are finding themselves in the middle of a contentious debate among parents over safety and other priorities.

Part of nearly every school district’s reopening plan has involved asking families directly when they would like to return to campus and under what circumstances. Now, school districts are facing the difficult realities of weighing a wide range of concerns while building trust among Black, Latino, special education and other parent groups who say their voices have been stifled.

Across the country, about 41% of parents said they want their child to participate only in distance learning under the current Covid-19 conditions, while 35% prefer fully in-person instruction and 21% would like a hybrid model that combines both in-person school with online classes, according to a nationally representative survey of parents by the USC Center for Economic and Social Research conducted from Jan. 20-Feb. 17.

What’s more, there’s a wide difference of opinion among parents of different racial, ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds. About 46% of white parents nationwide said they wanted in-person school, compared with 14% of Black and 29% of Latino parents. Higher-income parents were also more likely to say they wanted their kids to be back on campus compared with those earning less.

In California, recently ground zero for the pandemic in the U.S., parents are more reluctant to have their children return to the classroom. Only 14% of parents wanted in-person classes compared to 65% of parents who prefer remote-only instruction under current conditions, according to the same USC survey. Out of 1,330 adults who responded to the question, 455 were from California and demographics reflected the state’s overall population.

In West Contra Costa Unified, a large urban district that encompasses Richmond and surrounding communities, a recent district-wide survey conducted from Dec. 16 to Jan. 15 found that more than a third of parents prefer distance learning for the remainder of the school year, compared with only 15% who would send their children back to school under the current conditions.

Other parents said they only feel comfortable sending their kids back under certain safety criteria, such as if a vaccine for teachers was readily available (10%) or if a majority of the county had been vaccinated (14%). Another 14% were undecided.

But at a school board meeting in early February, district leaders pointed out a major caveat regarding the survey: Only a fifth of the district’s families participated, and white and wealthier families, such as those in El Cerrito, were overrepresented compared with the district’s overall enrollment.

“We obviously did see the El Cerrito community show up the largest in this survey,” superintendent Matthew Duffy said in the board meeting. District officials said there is not yet a plan to re-issue a reopening poll this spring.

Zip codes located in El Cerrito also have far fewer cases of Covid-19 than cities with more low-income families that West Contra Costa Unified serves, such as Richmond and San Pablo, according to recent data from the Contra Costa County health department. That is consistent with Covid-19 trends across the state, where Black, Latino and low-income families, as well as people experiencing homelessness, are often more at risk of Covid-19, partly because these groups are more likely to have dense living situations or are unable to work from home.

One major challenge with surveying parents is how quickly research and opinions around Covid-19 can change, said Bobby Jordan, public information officer for West Contra Costa Unified. In the weeks since the district released its reopening survey, California has opened mass vaccination sites, announced a $6.5 billion school reopening deal, and Covid-19 cases have dipped significantly. As conditions change, parent responses may also shift.

Jennifer Peck, a mother of a junior at El Cerrito High School, has become a vocal supporter of moving more quickly to safely reopening schools in West Contra Costa Unified. But like many, her stance on reopening has evolved as more information about virus transmission and vaccines have become available and seeing her daughter struggle with isolation from distance learning over a prolonged period of time.

“Evidence was coming out about infection rates in schools, and I was hearing more about districts that have been opened,” said Peck, who has been supportive of school closures while infection rates were high but said she’s been disappointed by the lack of transparent planning to bring students back. “It all culminated and by the end of last calendar year, we basically said we have to do something or there’s no chance our kids will be back in school this year.”

As Covid-19 cases have been on the decline across much of California, school districts in the Bay Area and beyond are taking temperature checks on reopening and finding issues similar to those in West Contra Costa.

Oakland Unified published the results of its parent survey in early January, showing that 41% of parents support bringing their child to school for some form of in-person instruction this year, while the vast majority of respondents said they were unsure or preferred their children to remain in distance learning.

White parents, who were overrepresented in the Oakland Unified poll compared with the district’s enrollment, like in other surveys were far more likely to respond “Yes” to bringing their kids back to campus.

“The overall results of the survey do not give a clear picture of our district as a whole because the survey sample is not representative of OUSD’s diversity,” the district website reads.

In Los Angeles Unified, a survey conducted in early December found just a third of parents said they wanted to send their kids back to school for a hybrid model that combines in-person instruction with online classes, while two-thirds they would like to remain fully online. A little more than a third of parents in the district responded; however, there was parity among the racial make-up of those who responded and overall student enrollment.

In Oakland, district leaders launched a new preference form in mid-February asking whether parents with children in grades TK-5 would send their kids back to their physical schools once the option becomes available.

While imperfect, the data from these surveys are an important tool for school districts and teachers’ unions to get a pulse on how families feel as they discuss plans to reopen campuses.

“I desperately wish I could provide the certainty that we all crave. In the meantime, we must keep engaging with this uncertainty while acknowledging the difficulty and stress that it brings us all,” said Oakland Unified Superintendent Kyla Johnson-Trammell in a letter to families on Feb. 18.

But even parents who are eager for in-person school to resume and have responded to calls for input lack confidence in the reopening process and their district’s communication with parents.

“The survey was so long and confusing, it didn’t really give me the option of saying the thing I wanted to say,” said Peck, the El Cerrito High School parent. “I desperately want my kid back in school, but we aren’t ready. I wasn’t going to say yes to that.”

Among the challenges that districts face in reopening campuses is a lack of proper ventilation in school buildings. At Richmond High School, for example, most classrooms do not have windows that open to allow for air circulation, which is recommended by health professionals.

“The reason why a lot of parents of color are concerned about reopening is that we already knew the state our schools were in before Covid. We didn’t have soap, schools weren’t clean and class sizes were too big,” said Shakira Reynolds, co-founder of the Parent Leadership Council in West Contra Costa Unified. “Now you want to couple that with Covid and without knowing what the plan is; it doesn’t make sense for a lot of folks how that would be OK.”

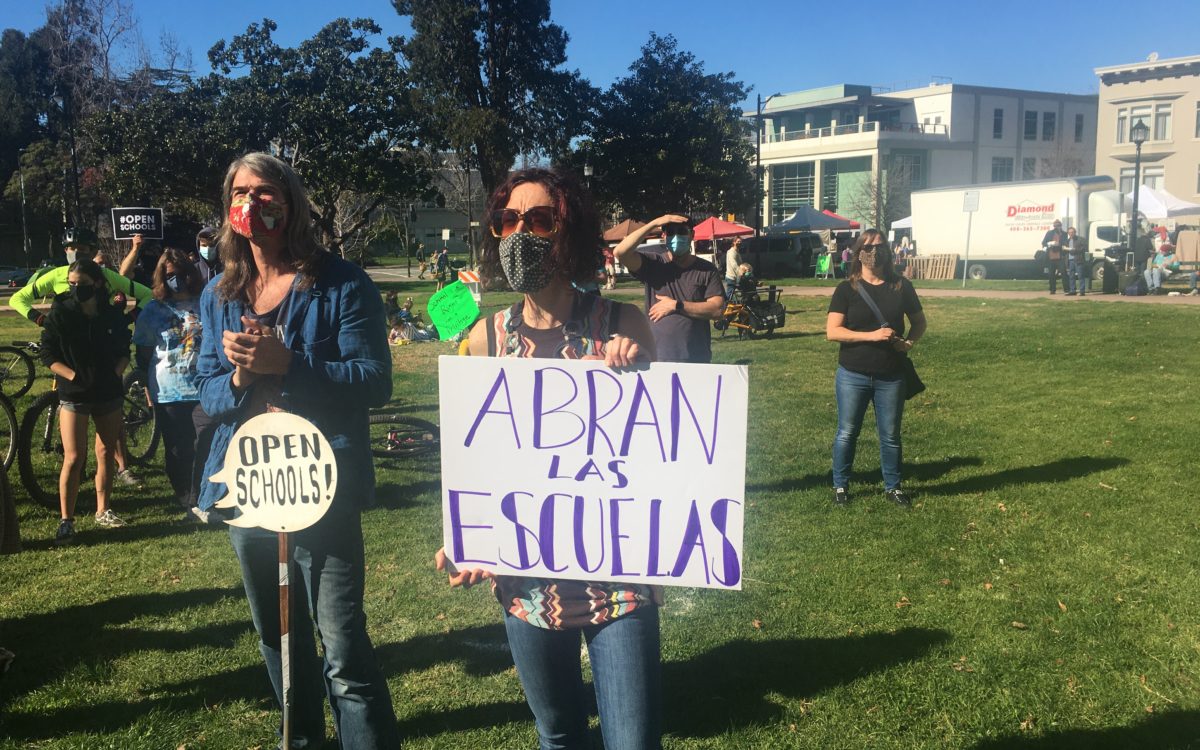

Across California, how and when to bring students back to their physical campuses has become a polarizing debate.

In January, a group called Open Schools California formed with the goal of encouraging schools to reopen as soon and as safely as possible. The group includes parents from Richmond, Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Diego and other cities.

“Locking older children out of the classroom ignores the science and data that shows school closures are impacting kids of every age. Schools are an essential public service and should be treated as such — the last institutions to close when cases spike and the first to reopen,” said Ross Novie, a parent and member of Open Schools California based in Los Angeles.

Supporters of the group point to growing evidence that supports strategies to reopen safely and that student mental health has deteriorated greatly since schools shut down last spring.

In West Contra Costa, a group called Safe Open Schools formed in December in support of reopening schools as quickly and as safely as possible. Recently, the group sent a letter to the school board and district leadership with about 450 parent and teacher signatures “urging implementation of a comprehensive plan for reopening as soon as possible,” said Kelly Hardy, a parent of a 3rd-grade student in the district.

To solicit parent input for its survey, West Contra Costa Unified District officials turned to their go-to communication channels: social media, automated calls home, text messages to parents, and through community partners such as churches and local media. When it became clear that the incoming responses were skewing towards wealthier schools in the district, they targeted outreach to schools that were less represented. Even then, only a fifth of parents responded.

“Parent outreach is critical. We always have to keep striving to get better to reach families and make sure we are doing everything we can to get information out to them,” said Jordan, the spokesman for West Contra Costa Unified.

Trust is proving to be one of the most challenging ingredients to bringing students back.

Some researchers have suggested creating an “infection control” or “healthy schools” team that community members can look to for updates and information on Covid-19 in schools.

Elena Silva, director of PreK–12 for the Education Policy program at New America, a nonpartisan think tank, advised district officials in West Contra Costa Unified to acknowledge and work to remove preexisting inequalities in schools, while being transparent and specific about steps taken to bring students back to a safe physical learning environment.

“Being honest is really important. Communicate about how hard it is but also stay as positive as possible,” Silva said. “Folks have been hearing for a long time that we don’t know how to handle it, and they need to know there are plans and that we can do it.”