“There’s this book called ‘The People Could Fly,’” says Tongo Eisen-Martin, San Francisco’s eighth poet laureate. “It was a book of Black folk tales, and in the title story of the book, there’s some Africans, so-called enslaved on a plantation, and the assertion of the narrator is, ‘The people could fly.’ They just forgot how. And one day, this old man goes up to somebody, and he whispers something in their ear, and they just take off. They remember how to fly, and they take off. It sounds corny, but that story stuck with me since I was a kid. If you could actually whisper something in somebody’s ear that would remind them how to fly, what is that? What poetry is that?”

San Francisco, it seems, is starved for poetic mobilization, an enlightened whisper in a withered ear bent by time and the bludgeoning of bureaucrats, those who have too long lined their pockets at the expense of the city’s purveyors of art, culture and joy. Eisen-Martin is a bracing answer to the technocratic pall, a social landscape he observes to be “an open air corporate campus.” Or, put another way, “This police state candy dispenser that you all call a neighborhood” (“The Course of Meal”).

It’s a grim picture of the city, but Eisen-Martin’s sober outlook is informed by his memory of San Francisco’s previous incarnation.

“I think San Francisco had a beautiful convergence of generations,” he says. “The power was very much in our hands. Was it beyond the contradictions of the United States? Nah. But there was a real beautiful people power that just had so many colors of its own. … It’s tempting to romanticize a pre-gentrified city, but it’s almost like nobody is alive now.”

Conversely, Eisen-Martin recalls an early life bristling with vitality and revolutionary potential. Born in the San Francisco Mission District to revolutionary parents, Eisen-Martin was named after Josiah Tongogara, a commander of the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army, who fought for Zimbabwe’s independence and the end of white minority rule.

“Growing up in a revolutionary home, all of the shoulders I stand on are not extracurricular,” he says. “They’re just like a Last Poets track, or a Gil Scott-Heron track. That’s just breakfast. So, in a way, the art and revolutionary culture in general was just what we were breathing.”

The result was a cultivation of “psychic confidence,” an ease into comfort outside of convention. All the while, Eisen-Martin’s poetry peppered his vision. “Words, lines were always running through my mind aggressively,” he says. “Poetry is kind of a thing I just couldn’t escape. Now I’ve come to understand that it’s almost how my mind engages with reality.”

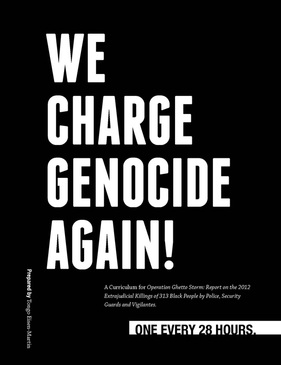

Shortly after earning his M.A. from Columbia University, Eisen-Martin published a series of lesson plans titled “We Charge Genocide Again!”, an elaborately constructed curriculum that interrogates the sociopolitical apparatuses that sanction extrajudicial killings of Black Americans. Truly a testament to the poet as teacher, Eisen-Martin offers a series of creatively provocative questions, like, “What type of person would kill someone who is innocent?”, and “If the corporation did not control the politician, what would change about the police?”

“The foundation of education has to be a liberatory practice, and specific to the task of whatever your slotted history is,” Eisen-Martin explains. “What all of these physical practices of resistance really come down to is how you see yourself, and how you see the world. That’s the beginning of a revolutionary development. So it’s a beautiful coincidence for us poets. You’re in perfect shape to do something about the insane reality you see.”

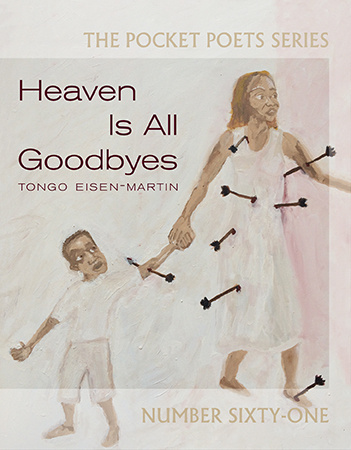

Just as Eisen-Martin’s curriculum is touched by his poetic imagination, his poetry is steeped in the wisdom of the wary, the enlightened resistance that follows the chill of disillusionment with American empire. In 2015, Eisen-Martin published a book of poetry titled “Someone’s Dead Already,” followed by “Heaven Is All Goodbyes” in 2017, which received both a 2018 California Book Award and a 2018 American Book Award.

In 2020, an independent U.K. press called Materials published a book of Eisen-Martin’s essays, interspersed with a few new poems, titled “Waiting Behind Tornadoes for Food.” Finally, on Jan. 15, 2021, Mayor London Breed announced Eisen-Martin as San Francisco’s eighth poet laureate, a title previously held by the likes of Diane di Prima and Lawrence Ferlinghetti.

Despite his swift ascent, Eisen-Martin remains grounded, eyes ever-fixed on the revolutionary potential of poetry. “I think, of all my limited but intermediate experience with poetry as a profession, the poet laureate position actually has the most proletariat potentials of anything I’ve seen so far,” he says. “Number one because it’s really run through the San Francisco Public Library. … Because the libraries are technically our territory, right? So moving the poetry away from implied towers is a potential for the position, or what I’m most enthusiastic about.”

Given his new title, Eisen-Martin intends to host writing workshops that double as exercises in social analysis. “I want to extend the revolutionary potentials of poetry to the whole village,” he says. “It’s a simple equation: It’s classes, and it’s microphones.”

The strain of social relations in a rapidly shifting city like San Francisco doesn’t deter Eisen-Martin’s visions of revolutionary change. “When I walk around, I fantasize about what a real unity would look like, where the people are safe and the ruling class is not,” he says. “Imagine people’s imagination roaring with more confidence. I just want a taste of that.”

In the meantime, Eisen-Martin has been working on a new book of poetry, scheduled to be published by City Lights Publishers in the fall. Left to his own devices in post-pandemic isolation, he developed “more of a meditative approach to the page,” in which the substance of the poem was secondary to the feelings seized.

“I have this new kind of technology of transmuting energy, and then I’m given all of this pain to transmute, so groovy new poems have appeared,” Eisen-Martin says. “The synopsis is really the backstory, but there is a lot on genocide, a lot on the principal contradictions of this society. There’s a plea, or implication, or a whining to the ancestors. There’s an outreach of sorts going on in there. … But, you know, it’s just another year of an anti-imperialist life.”

Eisen-Martin’s anti-imperialist aims have also inspired a publishing venture with fellow writer and friend, Alie Jones, called Black Freighter Press, a self-described “platform for Black and Brown writers to honor ancestry and propel radical imagination.” Upcoming releases include “Baby Axolotls y Old Pochos” by Josiah Luis Alderete, “Pendulum Under a Dead Clock” by Christopher Malec and “Out of Nothing” by the late Q.R. Hand, Jr., who Eisen-Martin describes as an “outer-worldly figure” and “the giant who got away.”

Regardless of what form it takes, Eisen-Martin’s work is an uplifting affront to the insidious banality of “the police state candy dispenser,” the gray pallor of corporate influx and the cynicism of the age. “There are just too many little geniuses running around here for me to think that the universe is done with this experiment,” Eisen-Martin concludes. “They wanna sow that despair in you, that maybe the nature of history is not evolution, that it’s not a transforming thing. But it is.”