This last year has changed us all, as a nation and its citizens, in ways that will continue to unfold and unspool for years to come. In 2020, a public health crisis, the coronavirus pandemic, met another chronic condition of this country: the longstanding, systematic violence against Black and BIPOC communities across the United States. With Black History Month in full swing in the Bay Area, in itself a nucleus of Black history, it becomes clear, the racial disparities in healthcare access, economic security and bodily safety have increased, but the systems that allow for these failings are not new. In fact, they are intentional.

Mere months before the world knew about the novel coronavirus, the New York Times released The 1619 Project, a journalistic endeavor that asserted the legacy of U.S. slavery was at the core of the nation’s founding — and that it has a hand in stratifying BIPOC communities nationwide to this day.

On Sept. 30, 2020, California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed, among other racial justice reform bills, Bill AB 3121, effectively opening the door for conversation and action around financial reparations to California’s African American population.

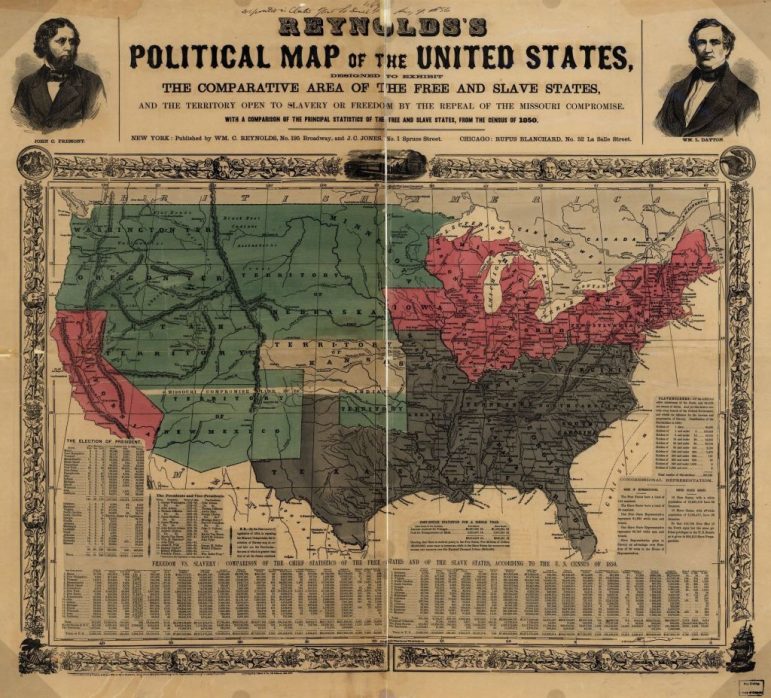

California was never part of the Confederacy and, at a glance, does not appear to factor into the North-South divide that defined the statehood process up until the American Civil War started in 1861; California entered the Union as a free state in 1850.

But to dig deeper and look critically is to see what’s hiding in plain sight. California’s first Anglo-American leaders leveraged the legality of slavery for personal gain, creating a racial hierarchy that sought to subjugate the bodies and labor of Black and Native Americans while withholding their rights to freedom, education and political franchise. These decisions ripple even now.

Dr. Stacey Smith is an associate professor at the University of Oregon who specializes in research about the intersection of the American West and the Civil War and Reconstruction period.

“I used to get a lot of blank stares,” Smith says of introducing her research; even many scholars don’t see how these topics are enmeshed. According to Smith, “the West, and especially California, has been treated as this exceptional part of the U.S. where slavery didn’t happen.”

But it did, for a very long time and to many different communities, not just African Americans, in what Smith describes as “different coercive labor systems crashing into each other,” including indentured servitude, contract labor and human trafficking.

It all began in 1492. Shortly after the first contact, Europeans asserted their imperialism through the religious mission system to convert and thus assimilate California’s Indigenous populations; the cities of Los Angeles and San Jose (among others) began as mission sites, and San Francisco’s own Dolores Park Mission was built by native labor.

Slavery of African Americans is typically associated with the Anglo-Saxon imperialists of the American colonies beginning in 1619. But the displacement and manipulation of African people began with the Spanish.

The National Park Service’s Park Ethnography program indicates many Black Spaniards in the 15th century chose to venture to the “New World,” be they conquistadors or subjugated workers, in the hopes of bettering their lot in life through land or freedom. Research shows hundreds of thousands upon thousands migrated voluntarily or were forcefully trafficked to the Americas up until the early 19th century, and most of them to what was then part of Spain’s empire in North America. All the while, Native Americans were systematically bound in labor, displaced, assimilated or murdered.

Jean Pfaelzer, Ph.D., an American Studies professor at the University of Delaware and California native who has extensively studied the circumstance of its statehood, credits the United States’ desire to maintain the institution of slavery as motivation for how quickly the West entered the fold.

By 1821, Mexico had won its independence against Spain, and the U.S. Congress had just passed the Compromise of 1820, wherein the states were formally divided into Southern slaveholding and Northern free states as Missouri and Maine entered the Union. Itching to procure more land in the name of “manifest destiny,” the United States went to war with Mexico in 1846. The U.S. came out of the peacemaking Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo of 1848 with more than half of Mexico’s original territory, which now comprises New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Colorado, Texas, Nevada and, of course, California.

“It was an expansionist war,” says Pfaelzer, who also has a book forthcoming on Yale University Press titled “Bound for California: The History of Slavery in California and the American West.” “Part of it was to gain more territory for plantation slavery in the West.” The week before the treaty was signed, California settler John Sutter and his employee discovered gold on his land; Sutter, a Swiss immigrant, was known to have enslaved hundreds of Native Americans since establishing his fort.

At the time of the discovery of gold in California in 1848, there was no constitution or legislative body. Mexico had abolished slavery in 1821, but the state was technically a territory, and white Southerners scrambled to take advantage of these legal gray areas on the West Coast.

“Many of the enslaved people coming are not aware that, the minute they crossed, they were free,” Pfaelzer says, because they were kept from the knowledge that they were no longer in a slaveholding state. Many abandoned their situations upon discovering their autonomy, but the law favored whites on account of most early politicians hailing from slave states.

“California is controlled by slaveholding Democrats in the 1850s and into the 1860s,” Smith says. “There is a legacy of pro-slavery leadership in California that we don’t know about or think about very much.”

One of California’s first U.S. Senators, William Gwin, was from Mississippi. The first elected California governor, Peter Burnett, descended from slave owners from Tennessee and explicitly expressed his belief that “it is the best humanity to separate two races of men whose prejudices are so inveterate that they never mingle in social intercourse, and never contract any ties of marriage,” in a public address.

“Slavery and the U.S. is not a North-South issue — it’s a national issue. This story of slavery as a divide is wrong,” Pfaelzer says. “This wasn’t hidden at the time; it’s been hidden in history.”

Newspapers at the time chronicled the debate of how California would enter the Union; white legislators acknowledged that slavery should be abolished and African Americans deserved civil rights, but did not want free Black communities in the state.

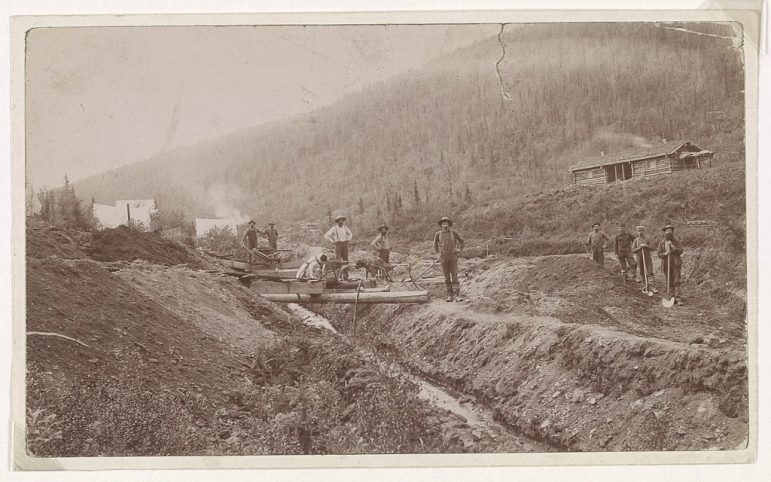

Walter Colton, the publisher of The Californian, speaking at the California Constitutional Convention at Monterey (Sept. 1 to Oct. 13, 1849), framed the issue of slavery more as an obstacle for poor white miners to profit off the Gold Rush rather than supporting the autonomy of enslaved people.

“The causes which exclude slavery from California lie within a nutshell,” he said. “All there are diggers, and free white diggers won’t dig with slaves. They know they must dig themselves; they have come out here for that purpose, and they won’t degrade their calling by associating it with slave labor. They have nothing to do with slavery in the abstract or as it exists in other communities … they must themselves swing the pick, and they won’t swing it by the side of negro slaves. That is the upshot of the whole business.”

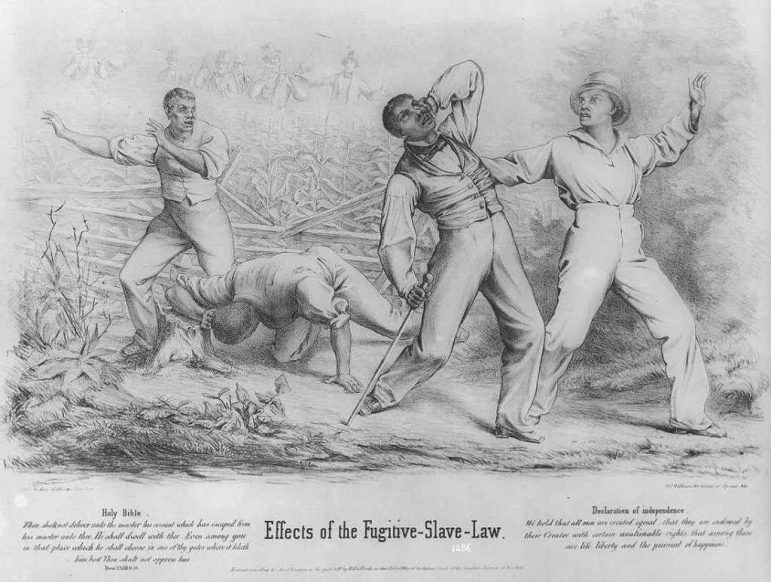

By 1852, California had its own Fugitive Slave Act, allowing white slaveholders to reclaim enslaved people who sought to escape, often with the help of local officials.

Pfaelzer calls this the “nascent policing system,” and it indeed reflects the failings of the justice system today. Having been barred any civil rights, Black and Indigenous (and later Asian) Californians had no right to vote or represent themselves in court; if they wanted to stand a chance at the freedom they were entitled to, they needed white support and representation.

Such is the case of Stephen Spencer Hill, an enslaved man from Arkansas who escaped his “master” after working in the gold mines with the help of a group of sympathetic whites, the Gold Spring Boys. The Boys not only shielded Hill and paid for his lawyers after he was arrested, but they were also essential in Hill’s final escape after he lost his court case. Most were not so lucky.

But there was a silver lining, at least to Pfaelzer. Free Black Americans from the Northeast states had also made the trek to access California’s resources and the possibilities the gold economy offered that the East Coast and Midwest could not.

These enclaves of free Black Californians created “thousands” of ignored petitions for the state legislature, and often traveled miles and miles to host Colored Conventions in churches and communal gathering sites to preserve their own access to rights as well as the rights of those who were previously enslaved.

“The Colored Convention movement is the first civil rights movement,” says Pfaelzer, with the fight primarily for the right to testify in court and protect their tenuous independence.

Historical research estimates that these systems of what Smith calls “unfree labor” in California weren’t fully extinguished until 1872 in the midst of the Reconstruction period, despite multiple attempts to maintain its power dynamics and disenfranchise or simply eject non-whites from the state. We know now, however, that as soon as integration and equity laws went into place, legislators all over the country went to work to overturn and worsen them.

California, for all its liberal reputation, went right along with this. Between the 1860s and 1940s, California flip-flopped on numerous racial and social issues, including voter registration policy, school segregation, interracial marriages and land ownership for minorities.

The 14th and 15th Amendments weren’t ratified in California, despite their earlier drafting, until the 20th century. It was also during this time that California, among other states, targeted the rights of Asian immigrants from China and Japan, barring them from voting, education and property rights even while extending the same liberties to other non-white communities.

While today most think of California as a left-leaning state that is progressive on issues like civil rights, its recent history includes voting for President Richard Nixon in 1968, who ran on anti-civil rights dog-whistles like “law and order” and “states’ rights,” and continuing to support the Republicans who embraced this strategy until Bill Clinton won the state in 1992.

Relieving California of its responsibility in the history of American racism dismisses the deep disparities it has tried to hide under its multicultural facade.

The United States of America has inaugurated its first female vice president, Kamala Harris, the first who is South Asian and Black, and the first from Oakland. It is still too early to tell how our country will come out of this pandemic, and how the state and federal government will address the inequity in losses, but we cannot move forward without looking behind us. Per Smith, “all history is political.”