Beating back covid right now comes down to balancing supply and demand.

With hopes pinned to vaccines, demand has far outstripped the supply of doses.

But, as an increasing number of vaccine vials are shipped in coming weeks, the concern about shortages may well shift to human capital: the vaccinators themselves.

“We need to mobilize more medical units to get more shots in people’s arms,” Jeff Zients, coordinator of President Joe Biden’s covid-19 task force, said at a briefing earlier this month.

Already, there have been scattered reports that vaccinators are in short supply in some areas.

“Absolutely, we do need more,” said Tom Kraus, vice president of government relations for the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, whose members work in hospitals, clinics and large physician practices.

After all, vaccinating America is a huge undertaking.

“We are planning to vaccinate a lot more people over a shorter period of time than we’ve ever done before,” said L.J Tan, chief strategy officer of the Immunization Action Coalition, which distributes educational materials for health care professionals and the public across a range of vaccination topics.

Each year the U.S. vaccinates 140 million to 150 million residents against influenza, “but what we’re talking about now is much more intensive,” he said. For covid, the goal is to get vaccines out quickly to all those eligible in a country of 330 million people.

A state-by-state survey would be required to estimate how many total vaccinators are needed nationally, Tan said.

Still, experts are cautiously optimistic that this won’t be a hard problem to fix, pointing to efforts underway to recruit current and retired medical professionals, as well as medical students and nurses in training.

“As long as we continue to see this interest in volunteering, we should have a sufficient workforce to do it,” said Deb Trautman, president and CEO of the American Association of Colleges of Nursing.

Not just anyone can be a vaccinator. One can’t merely walk into a center and offer to help give shots. The training requirements vary by state.

To boost the effort, both the Trump and Biden administrations, using an emergency preparedness law first adopted in 2005, expanded liability protections.

With the recent expansions, those qualifying include pharmacy interns and recently retired doctors and nurses, as well as physicians, nurses and pharmacists. The government estimates there are about half a million inactive physicians and 350,000 inactive registered nurses and practical nurses in the United States.

States are also greenlighting dentists, paramedics and other first responders, said Kim Martin, director of immunization policy at the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials.

Some are also turning to nursing and medical schools, where faculty and students are often eager to participate. More than 300 schools nationally have signed a pledge offering to help administer the vaccine, according to the American Association of Colleges of Nursing.

The University of Houston College of Nursing, for example, altered its curriculum specifically to prepare students for administering covid vaccines — and teams of students and faculty have helped at community vaccination sites.

Others are joining the effort.

The Medical Reserve Corps, a national network of volunteer groups, has more than 200 units in about 40 states, Puerto Rico, American Samoa and the Northern Mariana Islands assisting with various vaccination efforts, including administering the shots, according to a Health and Human Services spokesperson.

And the military is pitching in, too, with the Pentagon approving the use of more than 1,000 active-duty service members to help the Federal Emergency Management Agency with mass vaccinations sites, the first one set for California.

Although some of these groups give ballpark figures of volunteers, it’s hard to tally just how many have stepped forward in recent months to help vaccinate.

“It should not be left to just anyone that is willing, as there are clinical skills and preparedness that is required,” said Katie Boston-Leary, director of nursing programs at the American Nurses Association.

Even those skilled in giving shots may need a training booster in the war against covid.

When she volunteered, Boston-Leary said, she was required to complete four to six hours of online training across a wide range of topics, from the optimal way to administer intramuscular injections, to specific information about the two vaccines now on the market.

“Even a nurse like me has to go through that training,” said Boston-Leary.

To aid states in setting up training, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offered recommendations that all health care staff members receive training in covid vaccination “even if they are already administering routinely recommended vaccines.”

The CDC has different training modules, based on experience level. For instance, there’s a module for those who have given vaccinations in the previous year, but a different one for those who haven’t done so for more than a year. The time required to complete programs varies — people with the most recent experience require less total training time.

Tan said training laypeople with no medical background to give vaccines “is not the way to go.”

Instead, such volunteers can be used to help with logistics, such as directing people to the right areas, managing traffic, moving supplies around and similar duties.

Training programs exist even for people who aren’t vaccinators but assist with storing, handling or transporting the vaccines. That’s important because the two vaccines currently in use — one from Pfizer-BioNTech and one from Moderna — have different storage requirements.

They are shipped in multidose vials, which is not unusual for vaccines. The vaccinators themselves often draw up the syringes out of the vials, said Tan.

To avoid slowdowns as patients move through the lines, some vaccination centers have other trained staffers pre-fill individual syringes. Anyone doing this task should be “someone trained in administering vaccines as well,” said Tan.

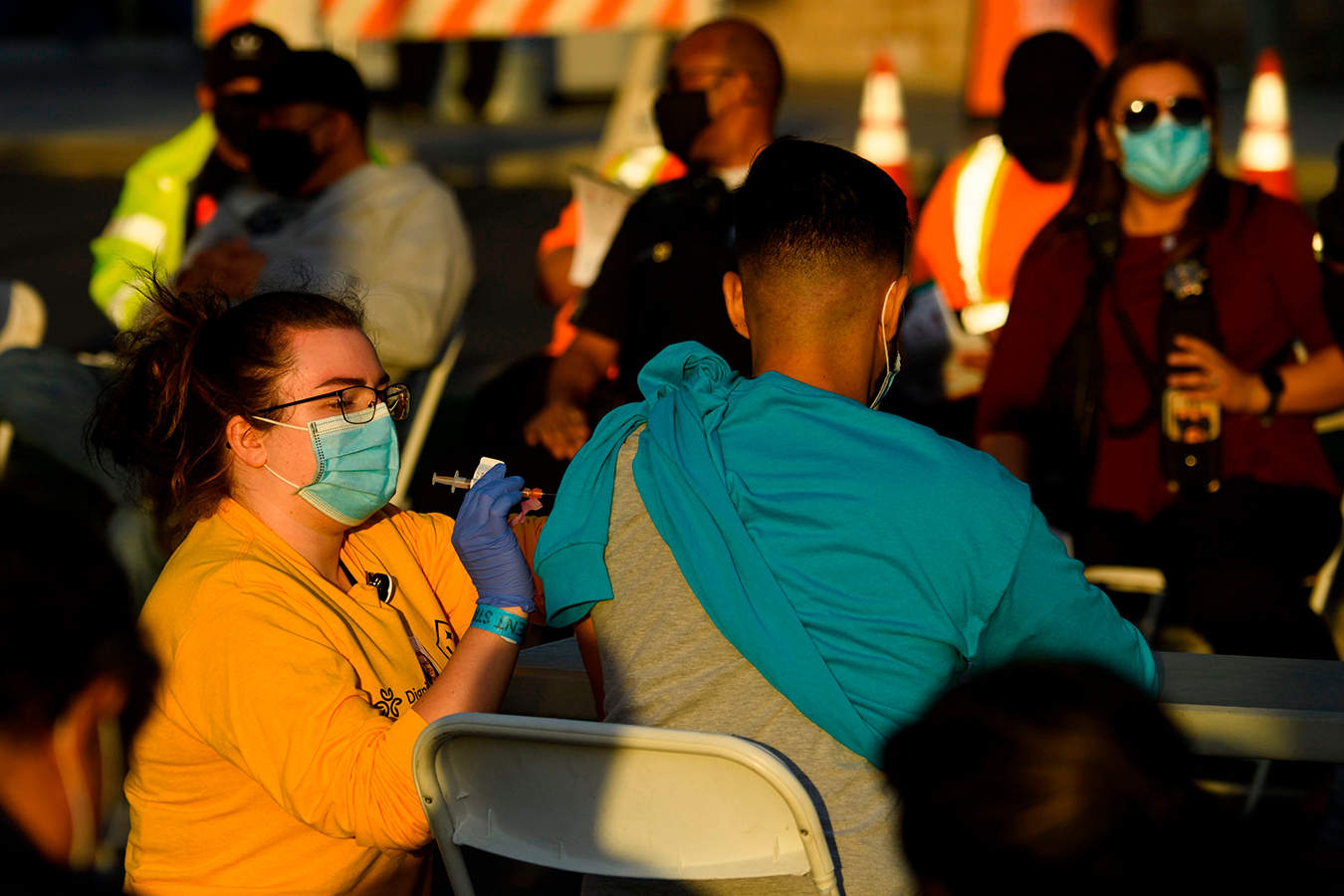

At the clinic where Katie Croft-Walsh, 65, volunteered recently in San Antonio, her only job was to administer the vaccine. Other volunteers took care of registering patients, pre-filling the individual syringes and other logistical efforts.

She decided to volunteer after hearing that help was needed. The move came with a bonus: She would get the vaccine herself at the end of her first day participating, something she already qualified for based on her age but had been unable to secure.

A practicing lawyer, Croft-Walsh previously worked as a registered nurse and kept her license current by taking required courses each year since leaving her hospital job in 1998.

Training occurred on her first day at the mass vaccination site and covered details about each type of vaccine, along with the types of syringes available, the right place to inject the dose and other information. Her group, which she said included nurses, dentists, pharmacists and upper-level nursing students, were trained and overseen by health department physicians.

The patients were all thrilled to get a dose.

“Everyone was very kind and nice,” even if they had to wait a bit in line, she said.

She liked the experience so much that she has volunteered at more clinics — and plans to start volunteering with fire departments as they begin community clinics in her city.

“It made me remember why I went into nursing in the first place,” said Croft-Walsh.

To ensure safety, training is important, Martin of the state health officers group said. It’s not that hard to give an intramuscular injection, but you need to place it in the right spot. For adults, that area is in the deltoid muscle, “not too far up the shoulder, not too far down,” she said, both to avoid injury and to make sure the vaccine goes into the muscle.

Training videos show vaccinators how to find the ideal location, first locating the bony point in the shoulder, then measuring two or three finger widths down and placing the needle in the middle of the arm.

Administering an intramuscular vaccine too high on the shoulder can cause a rare and painful injury. Such injuries were more common years ago when influenza vaccines were first rolling out, said Tan of the immunization coalition. Training on proper technique helped reduce cases since then, he said, and is also part of current efforts to train vaccinators.

It’s also important not to pinch patients’ arms when administering the vaccine, said Tan, responding to a question about a hashtag making the rounds on Twitter called #DoNotSqueezeMyArm.

For intramuscular injections to be most effective, the needle needs to penetrate the muscle, not fat.

“When you squeeze the arm, it pushes up the fat layers,” said Tan.

Those getting the vaccines, he said, can play a role, too.

“I encourage patients to ask questions,” said Tan. “If they’re concerned their arm is being squeezed, speak up. Not in a hostile manner, but say something like, ‘Hey, I read this thing about not squeezing arms. Can you explain why you’re squeezing mine?’”