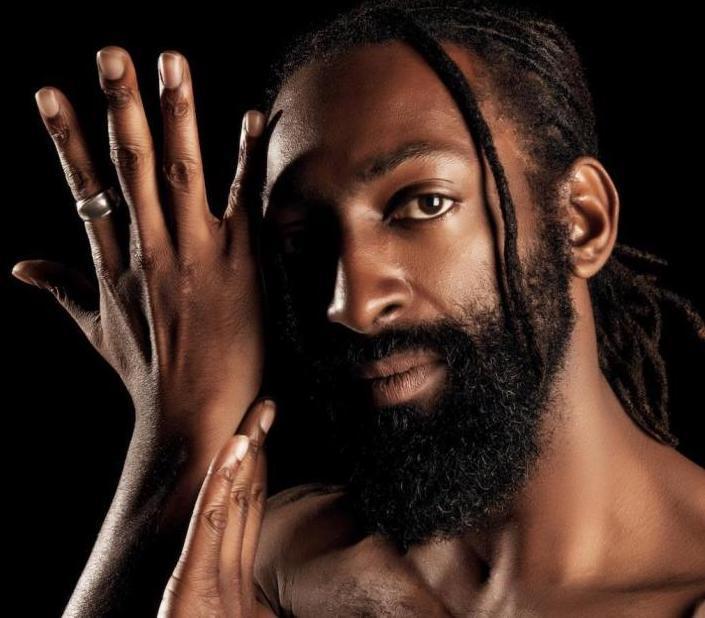

“I love being Deaf,” says Antoine Hunter. “I love helping people. I love being a part of the Bay Area.”

Hunter, a well-known Deaf dancer, producer and advocate, is the curator of the “Bay Area Deaf Arts” exhibition at the SOMArts Cultural Center in San Francisco, now on display in virtual space.

The exhibition showcases the work of seven Deaf artists from widely varied backgrounds. In curating the exhibition, Hunter wanted to create an opportunity for “everybody to appreciate the real talent of Deaf artists, especially people of color who are Deaf.”

Hunter, profiled in a piece by Lisa Hix in Local News Matters in August 2020, says that “art saved my life.”

When Hunter began to dance, he found there were few opportunities for Deaf dancers. He could have been defeated by that obstacle, but he founded Urban Jazz Dance Company to create a way for Deaf dancers to show their work.

That made all the difference, and over the years, he found that the art of Deaf dancers attracted interest from dance lovers from all over the world.

Perhaps as a result of his experience in dance, Hunter says that he “is always looking for talent and an opportunity to show that talent to the world.”

He knew from experience that the Bay Area was full of Deaf visual artists, but he perceived that opportunities for them to reach all audiences — hearing as well as Deaf — were extremely limited.

Hunter wondered what would happen if he brought Deaf painters, sculptors, fashion designers and mixed-media creators together.

He wanted to create a space where Deaf artists would feel welcome to share their work as artists. He connected with SOMArts Cultural Center — a venue on Brannan Street in San Francisco with a history of using its large space for “radical arts making,” according to a spokesperson for SOMArts.

Hunter found that SOMArts welcomed the opportunity to “learn how we work, how we present ourselves and uplift each other.” He was welcomed into SOMArts’ curatorial residency program and given an opportunity to bring his vision to life.

Hunter wanted it to be known that “there is not just one kind of Deaf person. There is Deaf blind, there is Deaf in a wheelchair, there are Deaf people who are Black, white, Asian, Latino …” He points to himself as a living example of the diverse parts of the Deaf community: He describes himself as “Cherokee and Blackfoot plus African plus disabled, plus Deaf plus I am in love with arts.”

“I wanted to give opportunities for other people to bring forth their voices.” He also wanted to give audiences an opportunity “to really look through the eyes of Deaf people from all kinds of identity.”

The latter was particularly important, not simply as a way to share their experiences, but because some people who are today able-bodied may find that one day that they can’t move, or hear, or see like they once did and then need to answer for themselves the question, “How do I still be part of the society?”

From his own lived experience, Hunter knows that many Deaf artists have had bad experiences when their work is presented by hearing people. He says sometimes those with hearing “don’t recognize how much damage they do to a Deaf person when they take control of something that may seem so small to them, but [when they do] they destroy the heart of the artist.”

Hunter said that he wanted to create a space where “we can say this is our home.”

The seven artists in the exhibition bring an extraordinarily wide diversity of life experience.

Deepa Agarwal left her home in India to get a master’s degree in graphic design from the Royal College of Art in London. From there, she moved to work at DreamWorks in Los Angeles

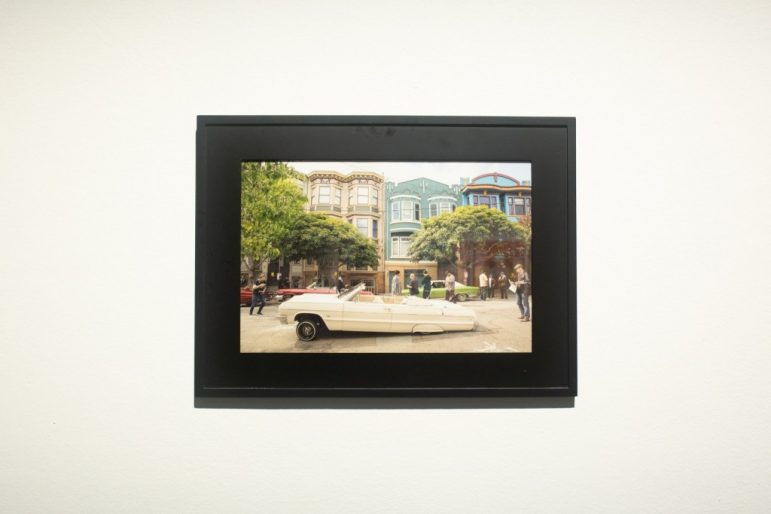

Drago Rentería is described in the program materials as a “Deaf, Chicano, heteroqueer trans man and a long-time LGBTQ/social justice activist based in San Francisco.” He is a photographer and photojournalist and has devoted years to documenting the changes brought about by gentrification to the Mission neighborhood in San Francisco.

Orkid Sassouni’s family left Tehran after the 1979 revolution, and she grew up in Long Island. She earned a B.A. from Gallaudet University and studied photography at Parsons.

clare cassidy is the mother of three Deaf children and a documentary journalist. She is passionate about basic human rights. Her powerful photographs of girls and women are collected in the exhibition under the series title “HER STORIES.”

Jon Kastrup holds a bachelor of science degree in mechanical engineering technology from the Rochester Institute of Technology and a law degree from Brigham Young University. He became a mixed-media artist after art therapy helped him deal with depression and PTSD.

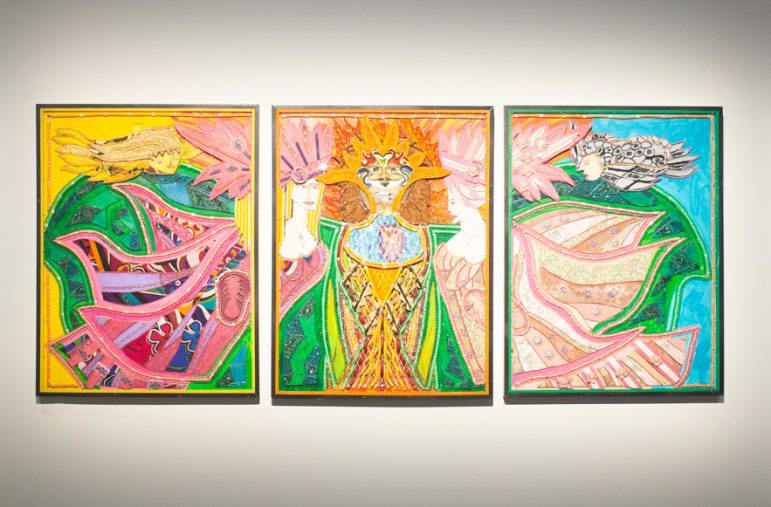

Gungaa Tuvshinbat was born in Mongolia and lost her hearing in childhood. She has traveled to 50 countries around the world. Her work uses her talents in “sewing, sculpting, reupholstering and painting surrealism.” Her striking multi-media installation in the exhibition demonstrates those talents and more.

ASL Love is not a single artist but a Bay Area organization that provides expressive space to Deaf artists “to share their artistic creations with the world and to support communities with resources & collaborations.” ASL Love’s website leads with video clips of improv performed in American Sign Language.

The exhibition is packed with powerful pieces, among them Rentería’s photograph titled “Riot.” He took the photo in 2014 when a riot broke out in the Mission after the San Francisco Giants won the World Series. That night, some parts of the Mission “resembled a war zone.” The San Francisco Police Department, wearing riot gear, “was out in full force, arresting dozens.”

Rentería was on the street in the midst of the chaos when he took the photo. It depicts a scene that could have been downloaded from the apocalypse: riot police blocking the street with smoke and gas billowing behind them, a debris-strewn Mission intersection lit by headlights and punctuated by glowing embers of red from a traffic light and the taillights of a car throbbing at the curb.

In the commentary accompanying the piece, Rentería wrote “Photojournalists sometimes place themselves in precarious situations to document what’s occurring. For Deaf photojournalists, photographing scenes like these and not knowing exactly what’s transpiring can make for some very dangerous situations.”

Another work in the exhibition by Rentería is a 17-minute documentary titled “A Glimpse Into the Heart and Soul of La Mission” that chronicles, without sound, the rich gumbo of life in the Mission in the period from 2014 through 2019 while forces of gentrification were roiling the culture and forcing rapid change.

The rich life of the Mission is shown through stills and clips of street festivals, parades, protests and parties, and is punctuated by cries for justice and freedom. He skillfully creates a narrative by weaving text from street signage, billboards and protest signs with the stills and clips to tell a story of the human impact of social change.

The decision to present the documentary without sound was an important artistic choice. Rentería says he had two primary reasons. First, “I wanted hearing people (and especially my Latinx Mission communities) to experience, if even for just briefly, what it’s like for me to experience these community events without sound and without communication access.”

The second reason was practical. “Because I’m completely deaf (I have no hearing whatsoever), I don’t know what kind of sound has been captured in the videos. … If I’m going to share something with you that I created, I want to know exactly what I’m sharing. Eliminating the sound gives me control over the video so that you experience it the way I do.”

Rentería’s soundless documentary creates an intimate experience and shows the tumult of Mission life in a self-contained and complete way, without ever diminishing the jumble of color, sound and flavors that intersect on the street.

The film is rich with dance. “Many of our events in the Mission are filled with music and dancing, which is a big part of Latinx culture. I wanted to convey that in the video.”

The political activism that runs through the piece is not heavy-handed but delivered through the arrangement of the photos and clips, as well as occasional wry commentary by juxtaposing images with text foraged from the street.

One stunning example is found in a single photograph. The viewer begins looking zoomed into a photo and sees a reflection in the plate glass of a storefront window: a street sign that says “F— Your Start-Up.” The camera then zooms out slowly to reveal a sign in the window of the small store that says in chunky block letters “CLOSED.” The camera then pulls back further and reveals a line of graffiti scrawled on the front wall of the storefront: “Why say ‘One Love’ when you mean ‘I want your home.’”

The striking, mostly black-and-white, photographs of clare cassidy show girls and women in moments of startling intimacy. One shows a girl in mid-flight on the beach with her family sitting behind her on the sand watching her jump. The girl looks as if she is about to leap completely out of the frame and into the viewer’s arms. The title? “Temporary Freedom.”

Another photograph catches a girl looking up to someone or something out of the frame, her hair garlanded with flowers, a look of quizzical attention on her face, as if she is being lectured by a grown-up, but one of ambiguous authority.

A third photo has a woman sitting in a darkened room, a child’s head buried in her lap. The woman’s arms are bare, and her hair is in curlers. She doesn’t look down at the child’s head but rather up and out a window that is just out of view. Her expression is a complicated mix of patience and longing and foreboding. You can’t tell her age; she is young and old at the same time. The title of the picture is “The Unspoken Burden.”

Each cassidy photo tells a story, and she gives the viewer the great pleasure of imagining what happened immediately before and after the instant that she has frozen in time.

The ASL Love work takes an entire wall to display. There are 26 separate panels, each painted with gaudy Day-Glo-ish paints — bursting oranges, electric blues, sizzling greens — colors so penetrative that you can feel them, an experience only made richer by the fact that wall is located behind curtains in a darkened room where the colors jump off the black wall.

Each of the panels is thematically devoted to a letter in the alphabet and displays a word beginning with that letter. The words follow the alphabet from A (“Audism”) to Z (“Zombify”). One set of five panels covers, consecutively, “Equity,” “Feminism,” “Gender,” “Hearing,” “Impaired.” Another sequential group is “No,” “Orgasm,” “Pleasure,” “Queer,” “Resist.” Above each word is the drawing of a hand that both displays the first letter of each word in ASL surrounded by colors that give vivid display to the essence of the word. Below each word, there is a phrase, a slogan, a cry, that amplifies the message.

The ASL Love work is a powerful artistic and political statement about the richness and varieties of Deaf experience and wholly in keeping with Hunter’s desire to show that Deaf individuals encompass the huge, bustling range of human diversity.

* The “Bay Area Deaf Arts” exhibition runs through Feb. 21 at SOMArts Cultural Center, 934 Brannan St., between 8th and 9th streets, San Francisco. For more information, click here: https://somarts.org/badaprograms/

* The exhibition includes a virtual gallery that can be accessed here: https://somarts.org/badavirtualgallery/