An Oakland-based community college district may soon be forced to cede power to the state if its Board of Trustees can’t quell concerns about its ability to properly govern the district.

Intervening at the Peralta Community College District, home to four East Bay colleges serving almost 30,000 students, would be a drastic step. Only twice previously has the state chancellor’s office and the systemwide Board of Governors assumed power from a locally-elected governing board: At the City College of San Francisco in 2013 and at Compton College in 2004.

The colleges in Peralta, one of 73 districts in California’s vast 116 community college system, are Laney College and Merritt College in Oakland, Berkeley City College and the College of Alameda.

Eloy Ortiz Oakley, the state chancellor overseeing California’s 116 community colleges, is under increasing pressure to intervene, including from former Peralta chancellors, two of Peralta’s current and former trustees, Oakland’s NAACP chapter and the Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team (FCMAT), a state-funded agency that provides financial oversight of K-12 and community college districts.

Those groups and individuals are calling for state intervention at Peralta to fix its problems: shaky finances, academic probation and what they call a broken relationship between trustees and top administrators. The district is currently fighting to keep its accreditation, with all four colleges having been put on probation last year by the Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges.

Oakley is expected to decide by the system’s Jan. 19 board meeting whether it is necessary to increase his office’s oversight of the district and possibly appoint a special trustee, who would likely have far-reaching powers.

Across its four colleges, Peralta enrolled about 29,000 students as of spring 2020, the most recent data available. Peralta students complete college at slightly lower rates than the state average. As of 2017, 45.5% of students received a degree or certificate or intended to transfer within five years, compared to the state average of 48.2%.

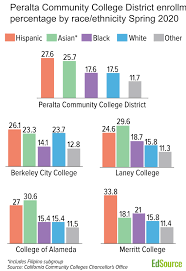

The district has a diverse student population: 27.6% of students are Latino, 25.7% are Asian, 17.6% are Black and 17.5% are white. The rest are either multiracial or their race is unknown, according to state data.

Tensions between the elected boards of trustees in community college districts and the presidents and chancellors whom they appoint is not unusual. But those at the center of the conflicts at Peralta say that what is happening in the district undermines the mission of the colleges.

In interviews with EdSource, current and former members of the district’s leadership, including the past three chancellors, accused the board of micromanagement. They said board members frequently interfered in their authority to perform duties, such as hiring executive staff and approving contracts. They also said the board’s leadership is closely allied with the faculty union in the district and focused more on appeasing the union on issues, such as collective bargaining, than on programs to help students reach completion.

“In all of my 35 years of working at community colleges, I’ve never seen anything like I’ve seen in the nine months I was at Peralta. It’s a very difficult place to be,” Regina Stanback Stroud, a veteran of the community college system who resigned as chancellor of the district in July, said in an interview with EdSource. She left her position as chancellor after only nine months on the job.

In the last two years, three chancellors have left the district after conflicts with board leadership. After Stroud departed the district last summer, the president of Oakland’s NAACP chapter called the board’s actions toward those chancellors “demoralizing” to Peralta’s Black administrators, faculty and students. Stroud and her two predecessors are Black.

The district’s other executive staff also has high rates of turnover. Currently, at least four vice chancellor positions are filled by either interim or acting staff members.

Board president Cindi Napoli-Abella Reiss, former board president Julina Bonilla and Interim Chancellor Carla Walter, who was previously vice chancellor of finance and administration in the district, declined to be interviewed.

“The signs are promising that we are on the right path,” district spokesman Mark Johnson said in a statement. He predicted that the district will be lifted off academic probation this month and noted that the district is in a better fiscal position than it was 18 months ago, when the state oversight agency that has reviewed the district’s finances, FCMAT, labeled Peralta a “high risk” of fiscal insolvency.

Jim Austin, a fiscal monitor appointed to the district by Oakley, said at a Board of Governors meeting last year that the district made “very impressive” progress on the concerns raised by FCMAT, which included budget deficits and staffing problems. Oakley appointed Austin to that position in fall 2019 after FCMAT’s report. In his role as a fiscal monitor, Austin was essentially a watchdog over the district but had no authority or powers.

However, he added that there is “another side of the coin” and said the district is plagued by “board governance and chancellor-board relationship issues,” which he said threatens the district’s long-term fiscal health.

Michelle Giacomini, the deputy executive officer of FCMAT, wrote an August letter to the state chancellor’s office voicing a range of concerns about Peralta, including “ineffective board governance.” She also wrote that systems within the district are “fully or partially controlled by highly influential special interest groups.” Giacomini said in an interview that the faculty union and other bargaining groups are among those groups.

“The Board of Governors should consider increasing its oversight role in the district over and above the current status of fiscal monitor,” Giacomini wrote in the letter, referring to the statewide governing board that oversees all 116 community colleges.

Peralta has a history of financial and board problems that predate most of the current board members. In fact, last year wasn’t the first time the colleges were put on academic probation. In 2010, the accrediting commission placed the colleges on probation.

The accrediting commission cited problems with board governance and criticized trustees for meddling in management of the district, according to a report at the time in the East Bay Times. FCMAT also previously visited the district in 2011 and issued a report criticizing the district for a lack of transparency around how it was spending bond funds.

The colleges were eventually lifted from probation. But in January 2020, all four colleges in the district were again placed on probation by the commission. In letters imposing probation on the colleges, ACCJC cited concerns including structural deficits, a “lack of adherence to board policies and administrative procedures” and “key staffing issues.” The commission did not elaborate on the reasoning behind those concerns.

A college is placed on probation when the commission has serious concerns about the college, but the college retains its accreditation during probation.

The accrediting commission made virtual “visits” in December to each of Peralta’s four colleges. Typically, the commission would make on-site visits but couldn’t do so amid the Covid-19 pandemic. Peralta’s Board of Trustees has also approved self-evaluation reports for all four colleges.

The accrediting commission will review those reports at its January meeting, at which point it will decide whether to lift the colleges off probation. The commission could also decide to take further action, such as withdrawing accreditation from the Peralta colleges. The three-day meeting is scheduled for Jan. 13 to Jan. 15.

Four of the seven board members who were on the board this past year were endorsed by the union the last time they were up for election: Bonilla, Reiss, Nicky González Yuen and Karen Weinstein. Those four board members typically voted in unison on most issues. Weinstein has since been replaced by Dyana Polk, who ran unopposed for that seat in 2020 and was also endorsed by the union.

Reiss, Weinstein and Bonilla also received significant campaign contributions from the union’s political arm when they last ran contested races for office. Bonilla received $7,500 from the union and related labor groups when she ran in 2014, 16% of her total contributions. Weinstein received about $11,000 in 2016, 21% of the total, and Reiss received just more than $20,000 in 2018, 36% of the total.

Campaign finance information is not available for Yuen’s last contested race for office, which was in 2004. He was subsequently re-elected unopposed every four years including 2020.

In her resignation letter this summer, Stroud accused the board of “collusion” with the union against the interests of the district. In an interview, Stroud said members of the board would regularly strategize and confer with the faculty union’s leadership on matters that should have been left to administrators to handle. Stroud’s view was shared by her two predecessors, Peralta’s former interim chancellor Fran White and former chancellor Jowel Laguerre.

For example, administrators said then-board president Bonilla circumvented the proper channels during collective bargaining with the faculty union in the summer of 2019. According to the administrators, Bonilla communicated directly with the faculty union president, Jennifer Shanoski, who was said to have complained to Bonilla that administrators rejected the union’s demand for a 10% faculty salary raise.

“That’s just so out of turn,” White, interim chancellor at the time, said in an interview, referring to the fact that the union felt comfortable enough to bring its concerns directly to Bonilla. White noted that those negotiations were the administration’s responsibility and not Bonilla’s. In the end, several months later, the board approved just a 3.3% raise.

Shanoski, the union president, said that it shouldn’t be considered problematic for the board to be pro-labor. “We certainly advocate for ourselves and our positions,” she said, noting that much of what they advocate for — such as smaller class sizes — benefits students.

This fall, the district sparked controversy when it decided to spend its $1.2 million portion of a state grant for Covid-19 relief to satisfy two agreements with the faculty union. The agreements were negotiated by Walter, the district’s acting chancellor at the time.

The district agreed to pay faculty $1,000 stipends for every course they convert to online instruction during distance learning and pledged to hire assistants for instructors teaching classes remotely with 35 or more students.

Bonilla, Yuen, Reiss and Weinstein voted to approve the spending, as did trustee Bill Withrow. Trustees Meredith Brown and Linda Handy abstained.

Why the district spent the money that way was puzzling to Brown, who has since retired. She said she would have preferred to see the money help provide students with internet access or with basic needs like food and housing. But according to Brown, the board never discussed how to spend the grant money.

Brown pointed to Laney College, the district’s flagship college, where student enrollment is down more than 20% this fall, a drop she said could be at least partly attributed to students’ financial difficulties.

“Giving the money to the people who are employed, while we’re losing students in multiple digits, doesn’t seem to honor the mission of the district,” Brown said. She was one of two trustees last year who called on the state chancellor’s office to intervene at Peralta, as did trustee Handy. Brown and Handy were the board’s only two Black trustees at the time.

Shanoski, the union president, said the district was obligated to pay faculty the stipends because the union’s contract with the district says faculty are supposed to be paid for time they spend transitioning classes to online. She also said the district has yet to spend most of the money that was set aside for hiring teaching assistants.

Johnson, the district spokesman, also defended the spending, saying it helped teachers adapt to new teaching methods during distance learning.

Walter has since been appointed interim chancellor and, unlike other recent chancellors, has the support of the faculty union. Shanoski in an interview praised Walter, saying she is “collaborative and has done an incredible job of learning on the job and listening to the folks with expertise.”

Handy, a trustee in the board’s minority, accused Walter of winning union support for her selection as interim chancellor after giving faculty the relief money. Walter declined to be interviewed and Johnson, the spokesman for Peralta, did not respond to a question about the merit of that claim.

Johnson added that the district can’t comment on the hiring process for Walter but praised her leadership amid the pandemic.

“Her calm and collaborative leadership style is everything the Board and the District desired during a period of dramatic change and challenges from COVID-19,” he said.

One of Stroud’s first tasks upon becoming chancellor was to replace the district’s financial system software, which she called “woefully out of date.” The state’s fiscal oversight agency (FCMAT) had found Peralta’s software for functions such as accounting and payroll presented a “significant risk to the district’s financial security.”

Stroud negotiated a $6.3 million new system with Oracle. The board rejected it twice and finally approved it on the third try.

To Stroud, the contract was an obvious solution to a glaring issue identified by FCMAT. And even though the contract was ultimately approved, Stroud said the back-and-forth highlighted a larger trend of the board micromanaging top administrators.

“That kind of stuff is what I’m talking about, where it takes a mountain of work to do what seems to be easy, normal stuff,” Stroud said.

Stroud also pointed to resistance from the board when she tried to make hires to her executive staff. In December 2019, her recommendation to hire a permanent vice chancellor of human resources was voted down. In March 2020, she tried to appoint a permanent director of marketing but that was also not approved. And last July, she attempted to renew contracts of three interim administrators, but votes on those extensions were tabled.

Stroud’s two predecessors, White and Laguerre, in interviews described being similarly micromanaged.

Those concerns are also shared by FCMAT. In her letter to the state chancellor’s office last month, FCMAT’s Giacomini wrote that there is often “micromanagement by board members.”

Bonilla, the former board president, said in a statement to EdSource that those claims “are without merit.”

The behavior of the board toward former chancellors Stroud, White and Laguerre, who are Black, caught the attention of Oakland’s NAACP chapter and the Peralta Association for African American Affairs (PAAAA), which represents Black staff and faculty at Peralta. The two organizations grew concerned that the board was not allowing the chancellors to perform their duties. Stroud said the voting bloc that she usually conflicted with included no Black trustees.

Lawrence VanHook, the president of the PAAAA and a professor in the district, said he had lost faith in the trustees after watching them refuse Stroud’s staff appointments and effectively “not recognize” her authority as chancellor.

He and others criticized the board for creating a culture that allowed what they viewed as racist remarks to be made during public board meetings directed at Stroud and other administrators. In one incident last spring, a white instructor, during a dispute with Stroud and four other Black administrators, said he would “not take lessons from my inferiors.”

Stroud said the comment was reminiscent of “a deeply white supremacist notion of the genetic inferiority of Black people.” The instructor later apologized, acknowledging in an email to administrators and the board that he should have known his words would be offensive. But neither union leadership nor the board leadership publicly denounced those comments, according to Stroud and VanHook.

“We have watched with dismay as successive African American leaders have come to the district to assume leadership, only to be treated with open contempt in public Board meetings and leave after a short tenure,” George Holland, president of the NAACP in Oakland, wrote in a letter to the state chancellor’s office last summer.

Peralta will likely learn its fate later this month, when the statewide Board of Governors convenes for a Jan. 19 meeting.

Peralta’s board leadership, faculty union and Academic Senate are strongly opposed to the possibility that Oakley, the state chancellor, will appoint a special trustee.

“Our democratically-elected Board of Trustees need to retain control of our district in the name of those who chose them as representatives,” Donald Moore, a professor of anthropology and president of the Academic Senate, said in a statement that he shared with EdSource.

In a preview of the decision he faces, Oakley said at a September meeting of the Board of Governors: “We know that there are several boards throughout the state that on any given day have conflicts with their administration. So the issue isn’t whether there’s conflict in the governance process. The issue is do they have the means and the mechanisms, the policies and the practices to work through them. So that’s what we’re focused on.”

White, the former interim chancellor at Peralta, said she has long believed that appointing a special trustee is the only option to fix the challenges the district faces.

“To be honest, I thought that in July of last year and I haven’t changed my mind,” she said. “Nothing has happened to make me think that a special trustee isn’t required to get that district back on track — whatever is left of it.”