What do you get if you add 12 and 21?

A unique art exhibition, one pushing the idea that society needs to take a new look at mass incarceration.

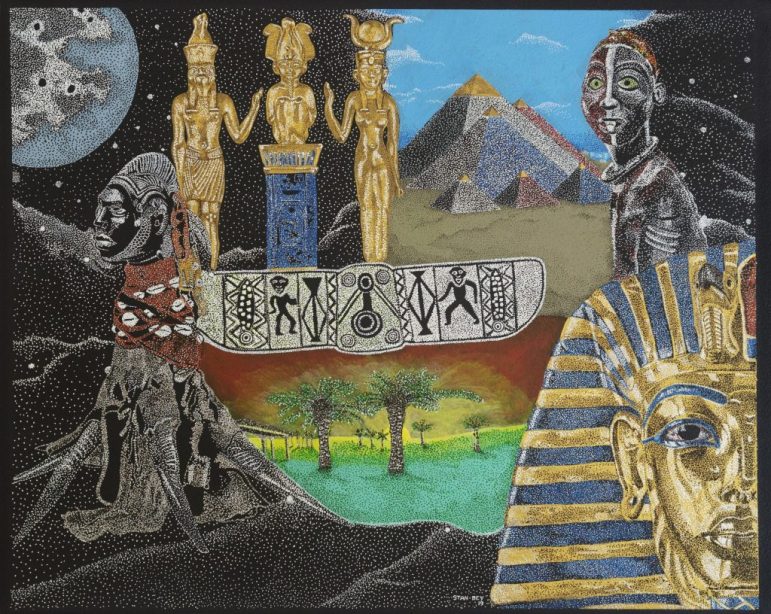

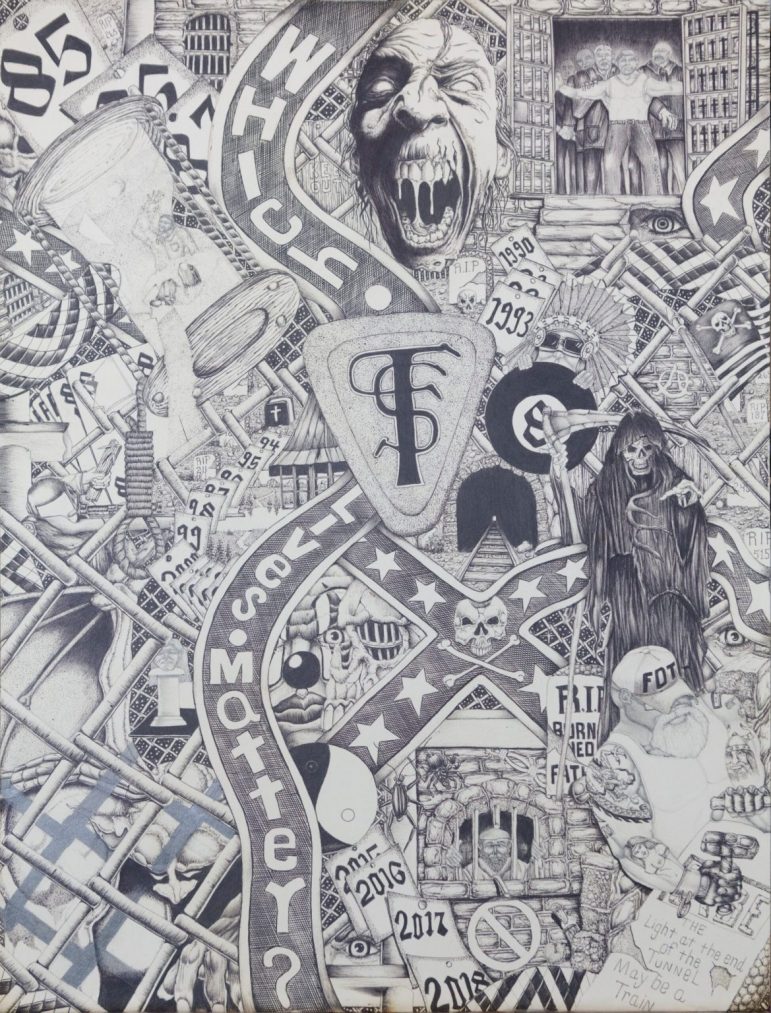

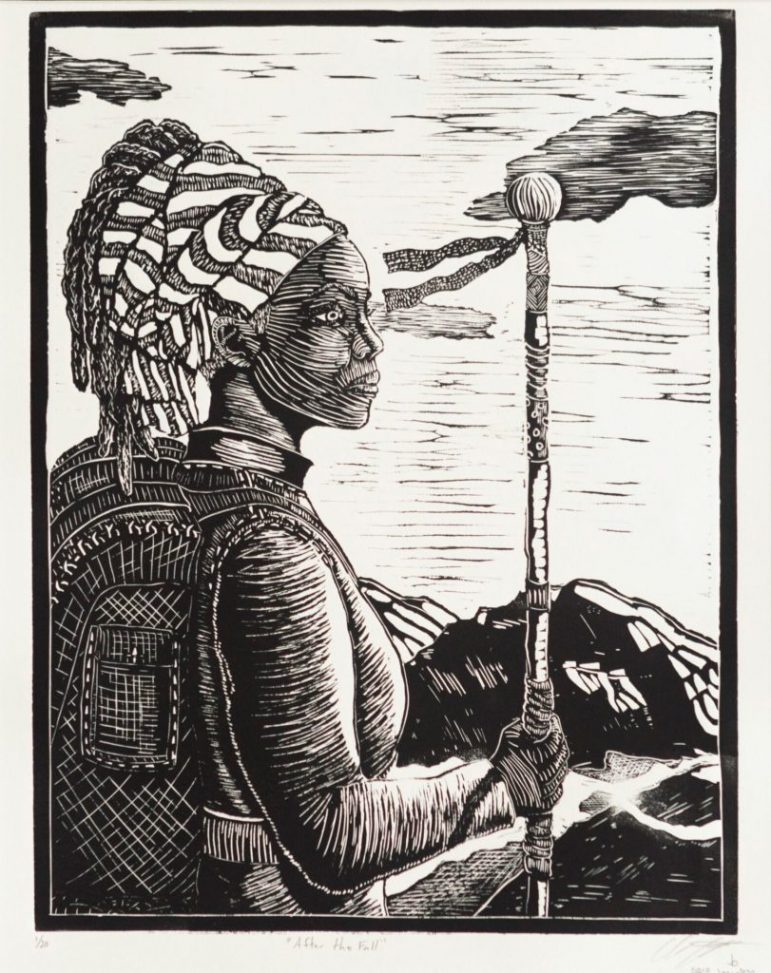

A dozen San Quentin inmates have contributed 21 artworks to the digital Museum of the African Diaspora (MoAD) display, “Meet Us Quickly: Painting for Justice From Prison,” which runs through Jan. 31.

In an email to Local News Matters, Rahsaan “New York” Thomas, its curator, says the exhibition features Black artists of whom he’s long been “a huge fan,” who “constantly give their art away as acts of amends.”

But in an essay accompanying the exhibition on the museum’s website — http://moadsf.org — Thomas voices displeasure with the justice system, which he contends “continues its removal of individuals without addressing the root causes of crime. Generation after generation face the same systemic issues.”

NAACP figures show that African Americans are incarcerated at more than five times the rate of white Americans. The organization’s research, furthermore, shows that “84 percent of Black adults say white people are treated better than Black people by police; 63 percent of white adults agree.” In addition, the NAACP website states, “87 percent of Black adults say the U.S. criminal justice system is more unjust towards Black people; 51 percent of white adults agree.”

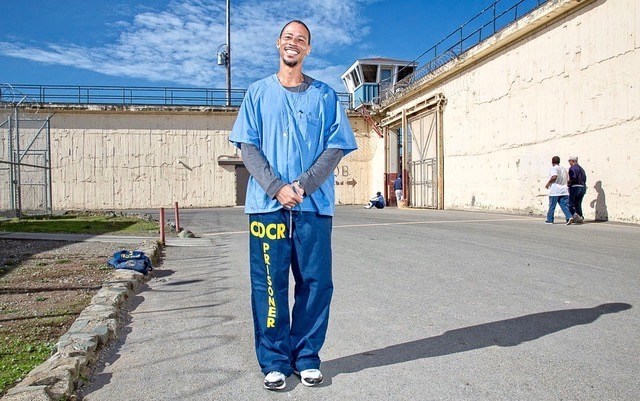

Thomas, a Black San Quentin prisoner who’s served 20 years of a 55-year sentence for killing an armed man he maintains was trying to rob him, wants to see the United States shift from mass incarceration to “preventing crimes [through] community investment.”

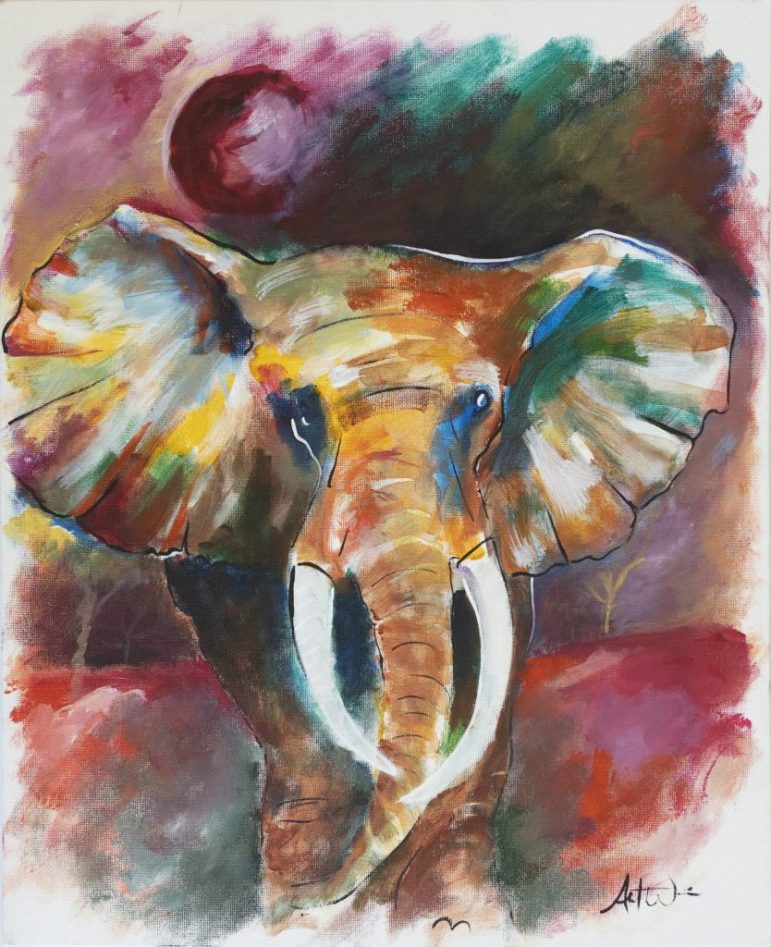

Meanwhile, he says, art lets inmates turn their “most painful experiences into something beautiful.”

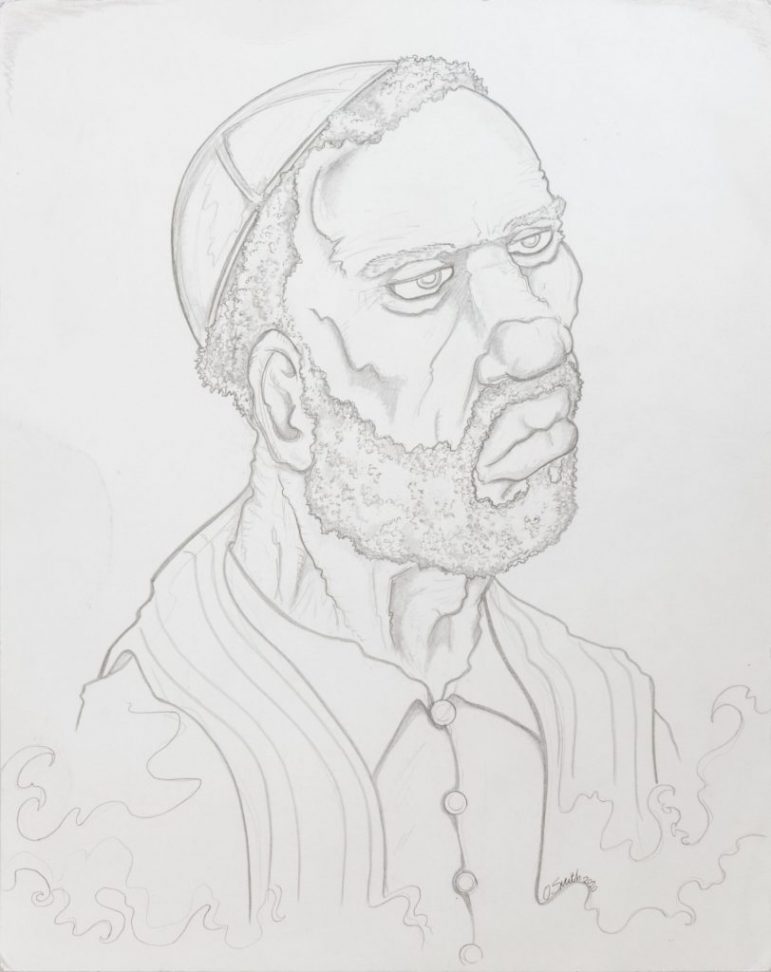

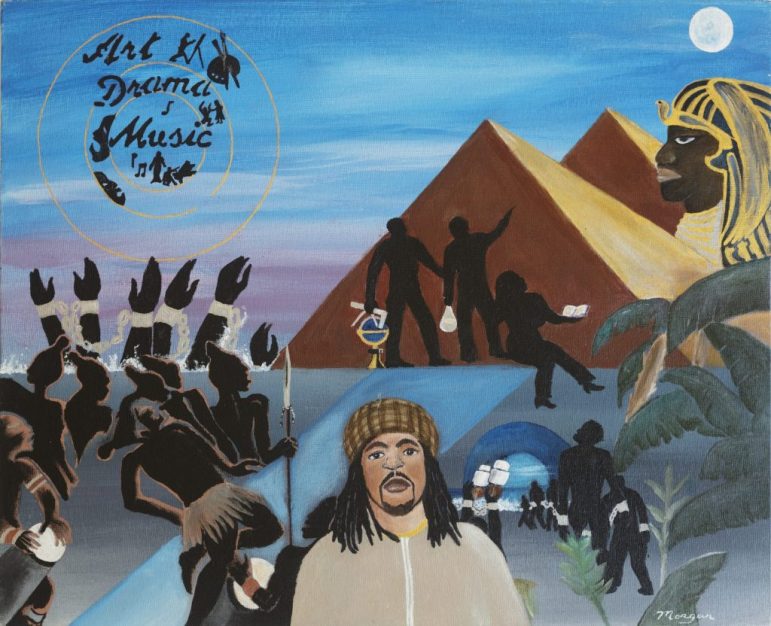

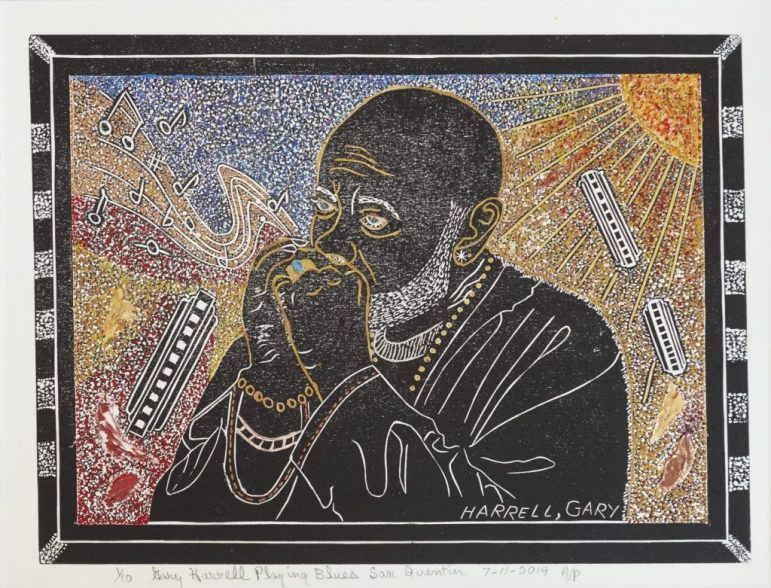

The eclectic exhibition includes linocut prints, acrylic paintings, ink drawings and collage, with at least one painting honoring Aaron Douglas, the African American muralist, illustrator and portraitist who emphasized social issues linked to race and segregation — and who was a major figure in the Harlem Renaissance.

Believing a joint effort could unite Black and Jewish people and simultaneously strengthen the call to curtail mass incarceration, Thomas had jumped at the chance to collaborate — along with MoAD — with Jo Kreiter, founder of San Francisco’s Flyaway Productions who choreographs apparatus-based, mid-air dancing.

Unfortunately, COVID-19 hit San Quentin hard last summer. Thomas — who co-hosts and co-produces “Ear Hustle,” the Pulitzer Prize-nominated podcast, from inside the prison — contracted it, and it forced Kreiter to cancel her dance portion. She hopes to reschedule it as part of a follow-up exhibition that Thomas is planning for July.

Meanwhile, Prison Renaissance, an organization Thomas cofounded, sponsored an online auction of the works in “Meet Us Quickly: Painting for Justice From Prison,” with roughly 85 percent of proceeds going directly to the artists, 15 percent to work that might lift up the incarcerated.

Money isn’t the reason exhibited artists do what they do, though.

Gary Harrell, a 64-year-old who’s been incarcerated 42 years, contends that he paints to hold onto his humanity. He says of his lino print on paper self-portrait, “Gary Harrell Plays Blues,” rather than Black men or white men, “we are all people of color searching for justice.”

Bruce Fowler, whose acrylic-on-canvas portrait “Ruth” is one of the exhibition’s most striking works, says, “My inspirations come from internal struggles that haunt me, places I dream of escaping to, and people I admire, which led me to paint [Justice] Ruth Bader Ginsburg [who] conquered unimaginable odds.”

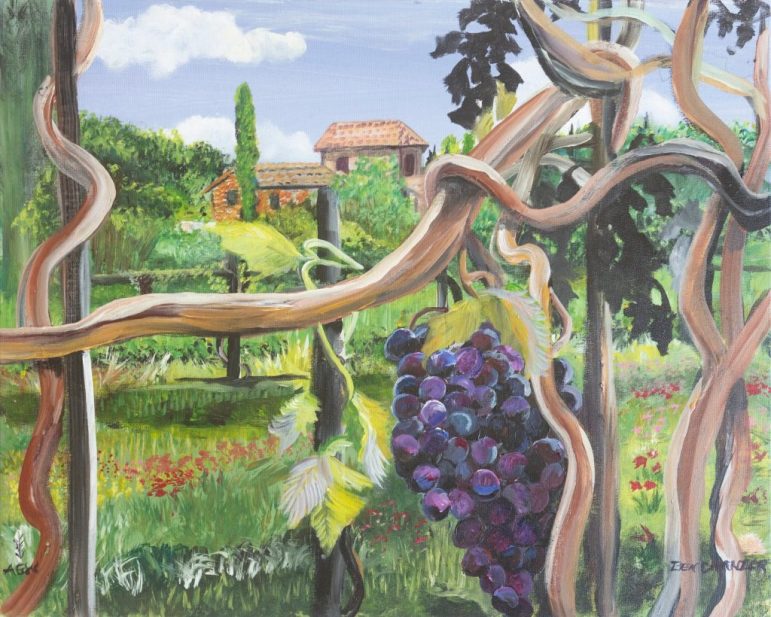

Ben Chandler, who says he paints “to keep my sanity and commitment to my children,” says he’s “a passionate and creative soul who loves to give back to communities as living amends for all the bad energy I have created throughout my life.”

Angela Davis once asserted that penitentiaries don’t eliminate social problems as much as they make human beings invisible. Thomas undoubtedly believes this exhibition — digital because the physical MoAD facility at 685 Mission St., San Francisco, is closed because of the pandemic — can help make imprisoned Black artists and their talent visible to the public.

Sadly, the convicts are no longer invisible — because the COVID-19 outbreak in the prison has made headlines. Well over 2,200 inmates have been infected, and at least 28 have died, including several on death row.

*To visit the exhibition, go to https://www.moadsf.org/