At 78, Navy veteran Robin Roberts has a place to call home again thanks mainly to the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs. His life is far from perfect, but he has come a long way from where he was two years ago when he had no place to live after losing his business and being evicted from his home in Mountain View.

He slept in a car in the driveway of a friend’s home in Fresno for about a month, taking showers in the house when the children were in school. Roberts contacted the VA, which told him about an arrangement with a shelter operated by HomeFirst Services of Santa Clara County, a first responder for homeless people in the county. He went there because he needed to go back to the county where he once lived.

But after cutting his foot in the shower and going to the hospital, he left the shelter after four months and moved into a one-bedroom apartment in San Jose. Many homeless people whose health is compromised on the street need to first get housing so that their illnesses can be treated, a San Francisco doctor and expert who studies homelessness said.

“We need to get people housed,” said Dr. Margot Kushel, a UC San Francisco professor of medicine who directs the school’s Center for Vulnerable Populations. “Then get them access to treatment for those illnesses.”

People who are chronically homeless are dying 20 to 25 years, possibly even 30 years younger than people who maintain their housing, according to Kushel and data collected by Bay City News Foundation. And, unfortunately the number of people who are dying homeless on the streets and in the hospitals of Santa Clara County is growing, up 350% between 2000 and 2018.

“If we really cared, we would be getting the housing,” Kushel said. “Everything else follows.”

The “housing first” approach is widely recognized as an effective response to chronic homelessness, but may be having just limited success here for a variety of reasons. The numbers dying are alarming. Between 2000 and 2018, more than 1,200 homeless people died in Santa Clara County. Most die in poorer areas of the county, many in close proximity to or in hospitals, which many cycle in and out of to get emergency care, according to data analyzed by Bay City News Foundation. Eight-five percent of the homeless people dying are men or boys. Children are not immune. At least six infants died.

Kushel, who’s also a professor of medicine at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, said that the obvious most important thing is housing and then other needs can be addressed.

“There’s lots we can do” and it’s easier to do those things when people are housed, Kushel said.

Perhaps it’s obvious that the solution to homelessness is housing, but it’s “housing first” that appears to be effective, instead of waiting until people have stopped using illicit drugs, recovered from a mental illness or started to work again.

A “housing first” approach appears to be working to end homelessness in Finland where the numbers have dropped steadily since 2007, according to the World Economic Forum.

Other successful efforts in the U.S., according to the Coalition for the Homeless in New York City, are federal housing assistance and permanent supportive housing, which pairs housing with case management and other services, and appears to help people who are chronically homeless.

Santa Clara County’s “housing first” approach was adopted back in 2010 and was reaffirmed during its “2015-2020 Community Plan to End Homelessness” development process, but the homelessness crisis doesn’t seem to be getting much better. For every person who gets housing, another person becomes homeless, data show.

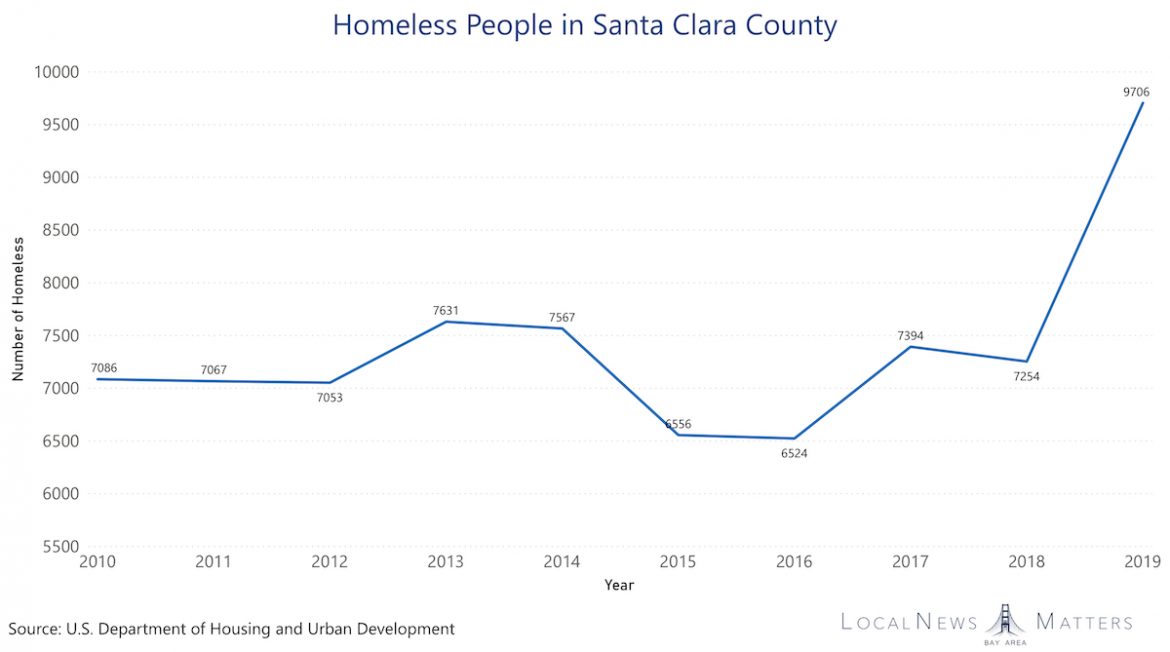

Nearly 10,000 people were homeless on any given night in Santa Clara County last year, according to the latest Point-in-Time count. That’s up from about 7,300 the year before and the most of any Bay Area county.

Since the reaffirmation of the “housing first” approach five years ago, the county has placed about 14,000 homeless people in permanent housing, a “good number” of those in permanent supportive housing, said David Low, spokesman for Destination: Home, a public-private organization to end homelessness in the county.

But even after homeless people are housed, at least those who most frequently use medical, psychiatric and other emergency services, they are dying at an extremely high rate of 17%, UCSF officials said following the announcement of a recent study conducted in Santa Clara County.

The study was a randomized control trial, a method where researchers use a test group and a control group to see if the intervention helped the people in the test group. The number who died in the control group was also about 17%.

“There were a lot of deaths because people were very, very sick when they were enrolled,” said Maria Raven, chief of the Department of Emergency Medicine at UCSF and a member of the advisory board of the Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative.

Raven is one of the authors of the study, along with Kushel and Matthew Niedzwiecki, an associate professor of emergency medicine at UCSF.

The study is promising in some ways. For example, the test group made less use of psychiatric emergency services and more use of outpatient mental health services.

“These people are so far down in their illnesses, you’re so far from primary prevention,” Raven said. “It’s an effective intervention, but it’s late in their life course.”

Roberts has medical problems, but they are minor. He said he has diabetes, nerve damage and trouble with his balance because “the gyroscopes in my ears don’t work.”

Eighty-six percent of the test group remained housed for several years. The study was published Sept. 17 in the journal Health Services Research.

The COVID-19 pandemic presents a different set of challenges to saving the lives of homeless people, but Project Roomkey, a collaboration of state and local agencies to put homeless people in hotels and trailers during the pandemic, offers some hope.

Homeless people are more at risk from COVID-19 because on-the-street access to sanitation and health care is limited, as are opportunities to isolate and quarantine.

In shelters, the virus can spread rapidly, so hotels, motels and trailers present an opportunity to give homeless people more of what they need to survive.

An even more promising initiative is Project Homekey, in which local public entities get money to buy and rehabilitate vacant apartment buildings, hotels, motels and other buildings to provide interim or permanent housing for homeless people.

The state is making $600 million available for the project. In the first round of disbursements by the state, $14.5 million was awarded to the city of San Jose to turn a 76-unit Project Roomkey project into permanent housing.

Like Kushel, Low said, “Housing is the true solution to homelessness.

“I would say that our biggest need is to continue to build more extremely low and supportive housing units,” he said. “This shortfall of affordable and available homes for our lowest-income residents remains the primary reason we see so many of our neighbors suffering on the streets.”

In fiscal year 2018, the Santa Clara County spent about $39 million to get homeless people into housing. That increased to $50 million last year and again the county will spend $50 million this fiscal year.

A review of the academic evidence around “housing first” strategies shows that “financial assistance and comprehensive housing support programs improve housing stability and prevent homelessness,” said Krista Ruffini, who holds a doctorate in public policy and co-authored a working paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research on reducing and preventing homelessness.

But she said, “There is still a lot we need to learn about what works and for whom.”

* This story was reported with support from the California Fellowship through the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.