Lea este artículo en español.

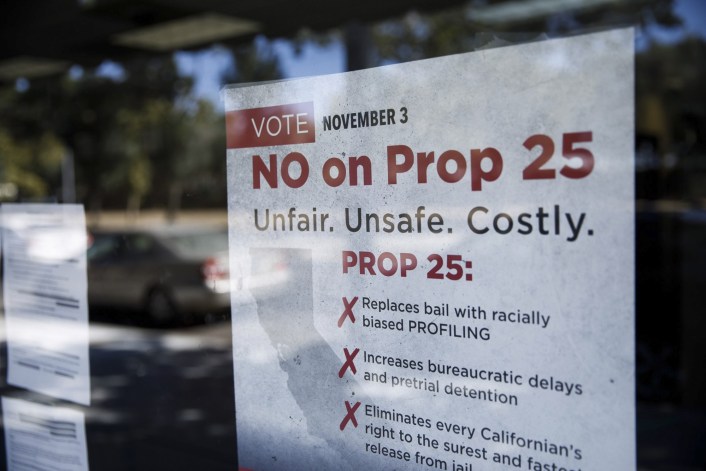

Proposition 25 would have made California the first state to end cash bail by allowing each county to use an algorithm to assess a person’s flight risk or likelihood of reoffending while awaiting trial. Supporters pitched the referendum as the Legislature’s best plan for advancing racial justice by upending a system that preys on communities of color and the poor for profit.

But opponents, including the bail industry fighting for its survival and law enforcement groups, argued the existing system could — and should — be reformed. They were joined by a small but vocal number of civil rights advocates who opposed or refused to endorse the measure.

Voters agreed. The unofficial count had Prop. 25 defeated, 55%-44%, leaving more work ahead for lawmakers and racial justice advocates to broker future changes.

“What I think they did say that this was not well thought out and needed work,” said John Lovell, a longtime lobbyist who has worked for law enforcement groups in Sacramento. “I think you’ll find general consensus that yeah, something needs to be done about bail schedules. But that fundamentally, the notion of having some incentive for someone to return for trial, is a sound notion.

“Now, is that exclusively money? Perhaps yes, perhaps no.”

The proposition would have affirmed a 2018 law, SB 10, signed by then-Gov. Jerry Brown to end cash bail by allowing a judge to decide whether to release suspects awaiting trial by consulting an algorithm that ranked defendants from low- to high-risk of flight or danger.

But civil liberties advocates were split. Some worried the passage of the proposition would have instituted a new system that came with the same racial and socioeconomic problems as cash bail, or worse. The Southern California branch of the American Civil Liberties Union opposed Prop. 25 while its northern counterparts remained neutral.

High among their concerns was the proposed expansion of the probation departments in each county, which would have been necessary to keep up with the proposition’s mandate that judges begin in most cases with a presumption of releasing a defendant.

“This proposition really looked like it was moving toward sort of the new frontier of criminal justice, which is mass surveillance,” said Alicia Virani, Associate Director of the Criminal Justice Program at the UCLA School of Law.

“We’re fighting a system that, through any which way it will reconstitute itself, is targeting people of color, is targeting communities of color, is targeting LGBTQ individuals, right? And so we have to look at the long game.”

In the aftermath of Tuesday’s defeat, supporters of Prop. 25 have their own rationales for its failure: the split within the civil rights community, the measure’s place on the bottom of the ballot (where fatigued voters are more likely to ignore or vote no on their options), confusing ballot language and a year of controversy over the algorithms used for pretrial risk assessment.

Democratic state Sen. Bob Hertzberg, who authored SB 10, said he was disappointed and worried about what it means for non-violent defendants locked up simply because they can’t make bail — the very people who would likely be released under the law he wrote. He said years of work went into brokering SB 10.

“We had hundreds, thousands of hours of meetings and calls,” said the Van Nuys legislator. “The legislation passed both houses. The governor signed it. We took guidance from the working group established by the Supreme Court of the State of California. And we passed the law.

“And then, you know, the bail industry comes along with millions of dollars and goes out and collects signatures and puts this on the ballot.”

Hertzberg said it’s too simple to call Prop. 25 a rift between progressives and more center-left liberals in California. Instead, he said, it was a divide between those who endured the wrenching process of compromise in 2017 and 2018, and a new batch of doubters who came along in 2020.

If anything, the map of how California voted on Prop. 25 captured the electorate’s mixed feelings in a year filled with protests over racial injustice.

In the Bay Area, which Democratic presidential challenger Joe Biden won handily, Prop. 25 passed. In traditionally Republican counties that went for President Donald Trump, including far northern California and the Central Valley, the measure failed.

But in every other blue or blue-leaning county, with the exception of Alpine on the Nevada border, Prop. 25 also failed.

In some of the most populous counties, it failed big.

Los Angeles County voted 55%-44% and the same pattern played throughout the rest of Southern California.

“It’s less of a celebratory feeling and more of a feeling of relief,” said Lex Steppling, co-chair of the Committee Against Pretrial Racism, which opposed Prop. 25. “What went from a flawed but decent bill turned into something, in our opinion, that was horrific and represented a potential crisis for communities in California.”

The Yes on Proposition 25 campaign vowed to return to the fight. The measure’s supporters outspent its opponents, $15 million to $8 million.

“As the bail industry continues to deepen racial inequities by preying on communities of color for profit,” the campaign stated Wednesday, “justice reform and civil rights advocates will not back down in the fight to build a justice system that treats every single Californian equally under the law.”

CalMatters reporter Laurel Rosenhall contributed to this report.

This article is part of the California Divide, a collaboration among newsrooms examining income inequity and economic survival in California.