We like to say the 19th Amendment gave women the right to vote.

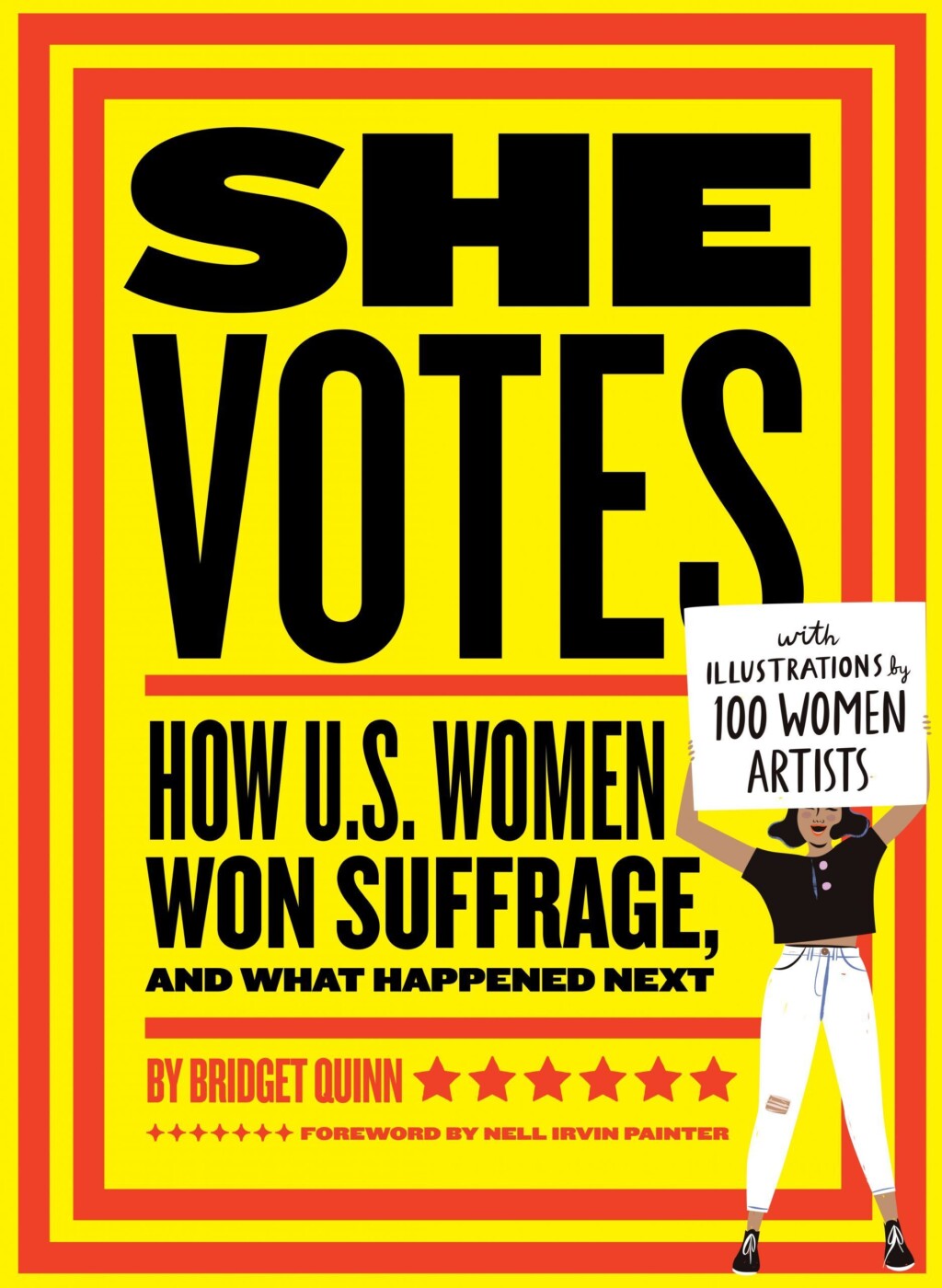

But Bridget Quinn, the San Francisco-based author who wrote “She Votes: How U.S. Women Won Suffrage, and What Happened Next,” has a different way of looking at the amendment that passed in 1920.

“The 19th Amendment did not give women the right to vote,” she says. “Women fought and died for it.”

The difference between women being given the right to vote (by men) and women fighting and dying after decades of being marginalized, ridiculed and abused is an important distinction — it’ll push your buttons as you flip the pages of “She Votes.” Quinn spent two years writing this primer on U.S. women’s history that bridges the stories that many of us know about suffrage leaders like Susan B. Anthony, with the little-known struggles that women of color endured before they could cast a ballot. Through it all, Quinn, a history buff and art history professor with a penchant for sports, lets loose with a witty writing style that’s entertaining and edgy.

Published by Chronicle Books in 2020, “She Votes” celebrates the 100th anniversary of women’s right to vote and includes images from 100 women artists. It takes readers from 1776, when Abigail Adams wrote to her husband, future U.S. President and then-Continental Congress delegate John Adams, asking him to give women a voice in American democracy, to the 2017 Women’s March on Washington that followed Donald Trump’s inauguration as president. We meet the women behind the fight for equality — from Boston Marathon runner Kathrine Switzer, to lesbian poet and activist Audre Lorde, to the “third wave” feminist riot grrl community.

Why create a book on suffrage that delves into the century after women won the right to vote? Because we’re not done fighting, Quinn says.

“Women told themselves, ‘We have the vote. We’re done; the fight’s over,’” Quinn says. “But there were other fights.”

This list is long. In the 1850s, women were expected to wear whalebone corsets and heavy, layered dresses that cinched their waists and made it difficult for them to breathe and move freely. Feminists popularized bloomer pants that made it possible for women to ride a bicycle and exercise. (In Chapter 5, Quinn quotes Susan B. Anthony in 1896, who said, “Let me tell you what I think of bicycling. I think it has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world.”) Another fight was to make the vote accessible to Native American, immigrant and African American women, not just white women. And then there were multiple voices shouting about having a career, and how that would kill a woman’s chances of marrying.

There have been many barriers to women’s equality. And there is still so much we need to do, Quinn says.

The best way to fight for women’s rights? Know your history. And VOTE.

“There is a lot of darkness in the past, and there is also joy,” Quinn says. “We have to know our history. We have to face it. We cannot know where we will go unless we know where we have been.”

The inspiration for “She Votes” came out of the 2017 Women’s March on Washington. Quinn was there, pussy hat in tow, and was amazed at the artwork and signage she saw in the crowds. Art was everywhere, and it was creative and bold, funny and poignant. She had just finished her book “Broad Strokes: 15 Women Who Made Art and Made History (in That Order),” and she was watching in real time how art was informing women’s history at the march. A few months after the march, her editor offered her an opportunity to write a book that celebrated the 100-year anniversary of women’s right to vote.

Chronicle Books commissioned art from 100 women artists. And Quinn dove into research and writing, using art as a lens to look at women’s history.

In the book’s introduction, Quinn tells us: “This is a true story. An adventure story.” It’s historic, about people who are long gone, but it’s also personal. We learn about Quinn’s journey, too. Prepare to be surprised by her research and narratives — and maybe a little heartbroken. Early in the book, we read about suffrage champion Elizabeth Cady Stanton lashing out with harsh, racist language after the Fifteenth Amendment gave African American men the right to vote, but not women. Could these heroines, who worked so hard for the rights women have today, have been less than perfect?

“These people did amazing things,” Quinn says of suffrage leaders like Cady Stanton. “But they were very flawed, too. My job as a storyteller is to be clear-eyed, and not be a cheerleader.”

https://youtu.be/O2CINq2MXWU

You can check out a great conversation with Bridget Quinn, Nell Irvin Painter and Tabitha Soren from Litquake’s festival in October.