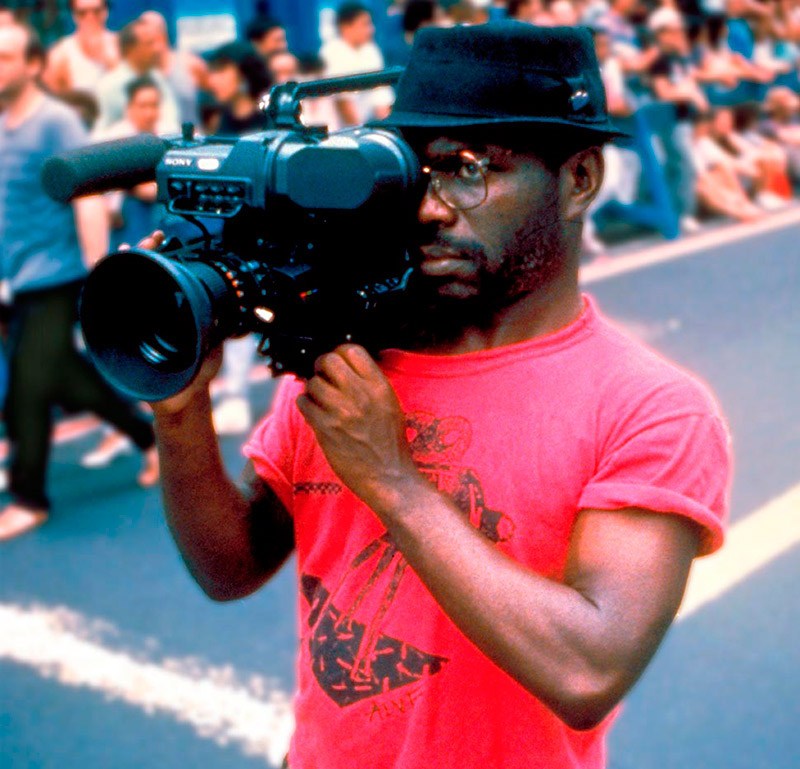

With a nation embroiled in racism, there’s no better time to revisit the vibrant works of Marlon Riggs, the late, great gay Black filmmaker who lived and died in Oakland.

A surge of revived interest in Riggs work is evident with audiences and scholars getting reacquainted or viewing for the first time the award-winning filmmaker’s informative, daring and often experimental documentaries, all of which unapologetically related the Black experience in America.

This week, our Pass the Remote column plays homage to the UC Berkeley School of Journalism graduate, professor and activist whose legacy as a bold artist continues to grow in prominence.

To understand why his works resonant with such power today, you can check out what two streaming services are offering.

The relatively new Ovid.tv recently released seven of the Texas native works. In October, the esteemed Criterion Channel will pay tribute to Riggs, whose “Tongues Untied” got Pat Buchanan’s dander up after it aired on PBS in 1989 and then became a talking point in the “Culture Wars.”

It will spotlight nine features in their “Race, Sex & Cinema: The World of Marlon Riggs” program, including a documentary on his life along with some shorts that were influenced by him.

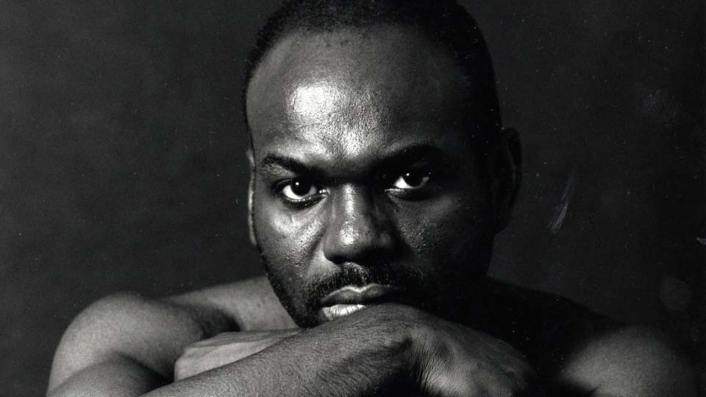

Throughout his short 37-year-old life, Riggs — who died due to AIDS complications in 1994 — blazed numerous trails and stayed true to his creative, rebellious spirit.

Riggs worked closely with producer Vivian Kleiman of Oakland via his East Bay production company Signifyin’ Works. Kleiman, who is now president of the business, related that the company’s mission from the start was “to create media exploring the history and culture of African Americans.”

The title of Riggs’ company illustrated what Riggs sought.

“The term ‘Signifyin’’ refers to the trickster archetype in African folklore —the man, woman or spirit who disobeys societal rules. So, I think that captures Marlon’s goals as an artist, educator, and activist who sought to challenge the so-called norms.”

Of his films, “Tongues United” is perhaps his best known. In 2019, 30 years after its release, Kleiman and Ashley Clarke, artistic director of the Brooklyn Academy of Music, teamed up for a popular retrospective of Riggs work along with the works that filmmakers influenced by him. Clarke worked with Criterion on their program.

“Even the additional late-night screenings of ‘Tongues Untied’ were sold out,” Kleiman recalls. “I was quite surprised and deeply moved to find that Marlon’s work was as impactful today as it was 25 years ago.”

Riggs has been praised for his work, but Kleiman remembers and admires her friend and collaborator for his tenacity and kindness.

“Marlon had both a mind of steel and a heart of goal,” she recalls. “He was a visionary artist who valued teaching over his own work, and who taught graduate students at UC Berkeley from his hospital bed when too weak from HIV infection to teach in person.

“The metaphor of gumbo in his final film ‘Black Is…Black Ain’t’ fits Marlon’s approach to filmmaking (stitching together all manner of filmic elements) as much as his personal community — a Jesse Jackson-like Rainbow Coalition of Inclusivity,” Kleiman said.

And that legacy only continues, from the filmmakers he influences, the awards given out in his honor (the annual Marlon Riggs Award from the San Francisco Bay Area Film Critics Circle) to the Marlon Riggs Papers stored at Stanford.

Here are short takes on the films you can now view at Ovid.tv: https://www.ovid.tv/marlon-riggs.

• “Tongues Untied”: Riggs’ best-known feature is an award-winning electrifying experience, one so unfettered that it fueled protests directed at PBS. Riggs ignores conventional nonfiction devices and creates a liberating template built around spoken word performances, historical footage and reflections from Riggs about being an out Black man in a most unwelcoming land. Most films, news shows and news stories at the time didn’t invite Black gay men to tell their full stories. Riggs raises their (and his) impassioned voices and it’s absolutely raw, real and liberating.

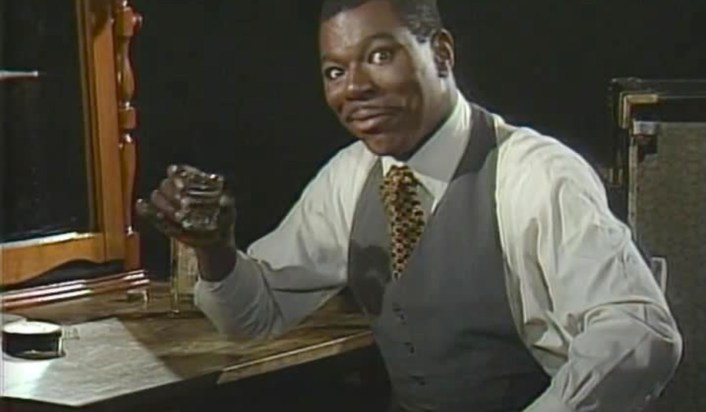

• “Color Adjustment”: Equally essential is Riggs’ update — a sequel of sorts to “Ethnic Notions” — that spans the early days of TV to the early 1990s. Here, he and producer Kleiman focus on how a post-WWII opportunity to fully integrate Blacks into American society failed to materialize while TV programs ignored Black characters or turned them into highly idealized notions. Particularly eye-opening are the forgotten TV series that ventured to portray Black characters and situations with more nuance. Sadly, both “East Side, West Side” and “Frank’s Place” lasted one season. Ruby Dee narrates with notable celebrities such as Rolle, Diahann Carroll, Tim Reid and TV producers offering insight.

• “Ethnic Notions”: Esther Rolle of TV’s “Good Times” narrates this Emmy winner, which contextualizes the racist stereotypes perpetuated in cartoons, movies and performances. Riggs adopts a more traditional approach for his first feature by showing examples and offering commentary from notable scholars such as the late Larry Levine of UC Berkeley. In one of its most powerful segments, Riggs takes to task the silent film “Birth of a Nation” (featured prominently in Spike Lee’s “BlacKkKlansman”) and links to the pro-Klan 1915 melodrama fueling hatred.

• “Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien”: In this candid, much-needed 38-minute documentary, HIV+ Black men share their feeling about a disease that was killing friends, lovers and perhaps eventually themselves, as well as candidly talking about their lives, dreams and sexuality. Released in 1993, it is a defiant revelation — a resonant patchwork of spoken word, performances and interviews with gay Black men. One interview is particularly affecting and haunting as a Haitian immigrant talks about finding out his diagnosis at the same time his mother had to put down the family dog. It’s crushing.

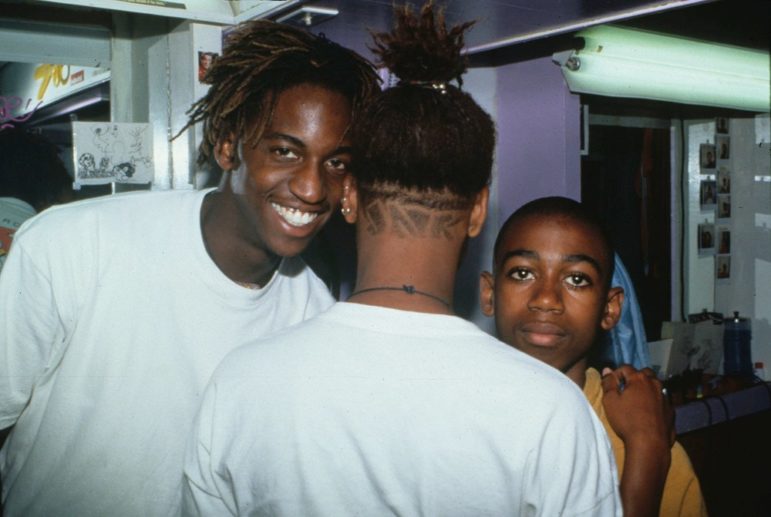

• “Black Is…Black Ain’t”: The most melancholy yet hopeful of Riggs’ features is also his final one, completed after his death in 1994. “Black” is a passionate document on what being Black in America was like throughout the years, intermixing interviews with Black leaders, activists, and teens in Inglewood, providing a dynamic, complex overview. “Black” is also personal and overwhelmingly sad with scenes of Riggs in the hospital as his T cell count plummets.

Short films

“Affirmations” (1990) and “Anthem” (1991): Both the playful 8-minute “Affirmations” and the riveting 10-minute “Affirmations” are more experimental in their approach in capturing the Black experience, fusing music, spoken word, interviews and images to do so. They’re frank, telling and at times sensual.