At first glance, it may appear there isn’t much opportunity in Piedmont for opening up housing to help increase diversity.

With the wealth gap favoring white families buying single-family homes — especially in tony communities like Piedmont — the city’s housing mix of more than 3,500 single-family homes and only 50 apartments may appear to ensure the city remains what Irene Cheng of Piedmont called “a wealthy white enclave, joined by a growing number of Asian Americans.”

But there are things the city and its residents can do to make their city more welcoming and attainable to people of color, according to Cheng, of the Piedmont Racial Equity Campaign (PREC), and two other panelists at a Thursday night Zoom presentation, “Racial Segregation and Housing in Piedmont: How Did We Get Here? What Can We Do About It?” organized by PREC and co-sponsored by the Piedmont Anti-Racism and Diversity Committee and the League of Women Voters of Piedmont.

At Thursday’s 90-minute presentation, panelists said Piedmont residents have the power to vote for ballot measures that call for building or preserving affordable housing in the region (and for candidates that support such actions).

“If you are not voting … you’re not doing the work,” said Gloria Bruce, executive director of East Bay Housing Organizations, which works to create affordable housing opportunities for low-income communities in the East Bay. She pointed to the passage in 2016 of Measure A1, a parcel tax measure to raise $580 million to produce and preserve affordable housing throughout Alameda County.

Piedmont voters could have done more four years ago, though, Bruce said – while Measure A1 passed with 73 percent of the vote countywide, only 52 percent of Piedmont voters said yes to it.

Added Cheng, “Most of us haven’t actively contributed to the segregation of our town, but neither have we acted to undo it.” One way to do so, she said, is for realtors who do business in Piedmont expand their networks to communities of color.

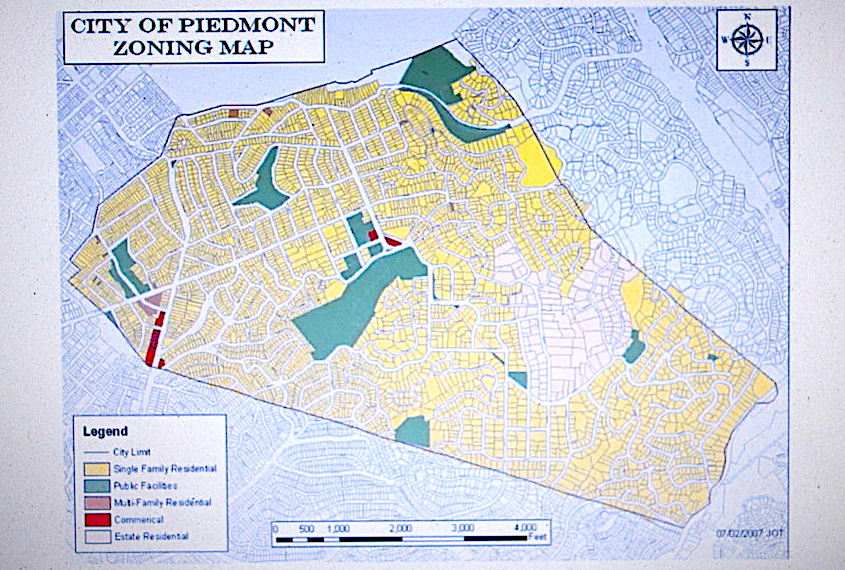

And while Piedmont is zoned almost entirely for single-family homes, new state laws make it easier for homeowners to create accessory dwelling units (also called “granny flats” or “mother-in-law units”) from converted garages, separate cottages or other residences on the same lot as a main dwelling. The laws are specifically intended to help increase the state’s stock of affordable housing, and therefore encourage a more diverse community.

The Piedmont City Council has had early conversations about increasing Piedmont’s ethnic diversity in general, and about accessory units specifically as a key way for the city to help get that done.

And in August, the council approved a formal repudiation of racism, what councilmembers saw as a beginning in an ongoing process to make Piedmont a more inclusive and equitable city. That came as the nation was undergoing a “racial reckoning,” as some have called it, a social justice awakening set off by the death in May of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police officers, and encompassing many other similar incidents of Black people dying at the hands of police. The nation is dealing with it again this week, with protests in several American cities after a grand jury indicted only one of three officers connected to the killing of Breonna Taylor in Louisville, Ky. in March.

Housing equity is one piece of the city’s ongoing response. But there are decades of housing segregation, both overt and nuanced, to overcome. Piedmont — like many other cities in the United States — has its own history of housing segregation.

Among the most blatant occurrences was the story of the family of Sidney Dearing, acknowledged as Piedmont’s first Black homeowner. He was forced to sell his Wildwood Avenue house to the city in 1924 after he and his family were mercilessly harassed and threatened; in that case, the city’s police chief aided and abetted the persecution.

Cheng said racial covenants and deed restrictions on homes, discrimination aided and abetted by local government and “redlining” (not offering loans to buy homes in areas deemed risky) have all been part of the city’s past.

Piedmont, Carol Galante said, was essentially built out by the 1920s with its overwhelming preponderance of single-family homes. And home ownership has been a key ingredient for middle-class families to build wealth, that has, she said, been mostly for whites.

While many of these subtle forms of segregation were put in place decades ago, “Most of us would agree that it still has an exclusionary impact,” said Galante, faculty director of UC Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation, and a Piedmont resident.

As for the more subtle forms of segregation, Galante said “racial zoning” has been practiced in many places in the United States. One form is approval by local governments of restrictions on where apartments can be built.

Given the limited number of buildable parcels in Piedmont, and goosed by state Regional Housing Needs Assessment requirements for future housing which regional officials expect will rise dramatically over previous cycles, Cheng said Piedmont leaders may need to reevaluate “sacred cows” about what housing will be allowed, and where.

“We just have to open up our minds and rethink things that seemed impossible before,” she said.

Contact Sam Richards at sam.richards4344@gmail.com