That Mother Nature has the power to nurture our Covid-shaken spirits these days is undeniable – witness, if you will, the mass flocking of solace-seeking humans to the hills, parks and forested trails of the greater Bay Area.

Many of us are also prompted to wonder as we wander about some of the mysteries the natural world harbors – what is that strange-looking plant, which bird is behind that shrill trilling, how is it that a puffy cloud amassed so suddenly in that stunningly blue sky?

One of the upsides to the pandemic is that it has left so many of us with time enough on hand to let our curiosity take us exploring – in books that have something revelatory to tell us about our natural surroundings.

Unsurprisingly, the publishing world stands ready to satisfy our cravings: Here are some recently released works of nonfiction that shine new light on some aspects of our outdoor environment.

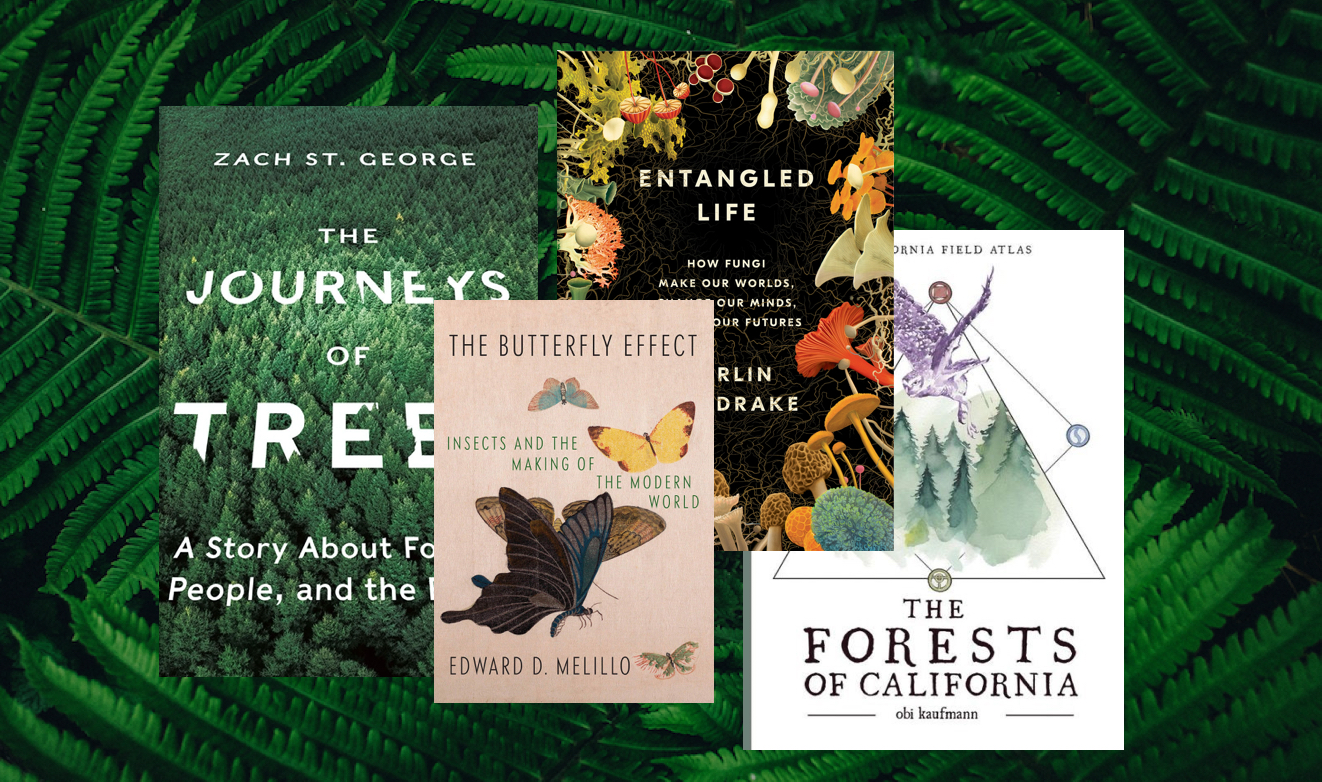

Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds & Shape Our Future

by Merlin Sheldrake

(Random House, $28, 380 pages)

Released in mid-May from British tropical mycologist and first-time author Sheldrake, this book achieved almost instant best-seller status among the multitudinous books about mushrooms, over which it currently resides at No. 1 on Amazon. Among its chief virtues, besides its depth of research and its often startling revelations, is the lush quality of its prose. The Bay Area’s own Michael Pollan, author of “The Botany of Desire” and “An Omnivore’s Dilemma,” was featured in conversation with Sheldrake at a virtual book festival event in July and calls him “a scientist with the imagination of a poet and a beautiful writer,” adding that “this book, by virtue of the power of its writing, shifts your sense of the human.” Sheldrake’s thesis that the fungi beneath our feet possess communication superpowers we can learn something vital from makes for riveting reading.

A heap of Piedmont white truffles (Tuber magnatum) sat on the scales on a check-patterned rag. They were scruffy, like unwashed stones; irregular, like potatoes; socketed, like skulls. Two kilograms: e12,000. Their sweet funk filled the room, and in this aroma was their value. It was unabashed and quite unlike anything else: a lure, thick and confusing enough to get lost in.

from Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds & Shape Our Future

Copyright © 2020 by Merlin Sheldrake, Random House, all rights reserved

The Journeys of Trees: A Story About Forests, People, and the Future

by Zach St. George

(W.W Norton, $26.95, 256 pages)

Science reporter St. George, who earned his journalism degree at UC Berkeley, brought us this lucid investigation into the migration of forests (and yes, they do indeed move, sometimes faster than you might realize) in mid July, focusing on five particular species: the Monterey pine, the ash, the giant sequoia, the black spruce and the Florida torreya. His research crossed continents, bringing him into contact with numerous foresters, biologists, conservationists, ecologists and passionate advocates for the preservation of the environment. It is a study on the impact our changing world has on the relationship between trees, the land they root in and the humans whose lives they support. J.B. McKinnon, author of “The Once and Future World,” hails it as “a fascinating, eloquent and often surprisingly funny journey into the troubled relationships between people and trees in a future that is now.”

More than any other living thing, trees define their surroundings. They break up the horizon, mark the trail, soften hard edges. You can pick them out one by one, a single thread, or as a texture, the whole cloth. Entire scenes can be conjured by the presence or absence of trees: the forest; the field; the house on the corner with the maple in the yard. As a tree is a rooted thing, so a tree is also a place.

from The Journeys of Trees: A Story About Forests, People, and the Future

Copyright © 2020 by Zach St. George, W.W. Norton, all rights reserved

The Butterfly Effect: Insects and the Making of the Modern World

by Edward D. Melillo

(Knopf, $27.95, 272 pages, illustrated, released Aug. 25)

Melillo, a professor of history and environment at Amherst College, opens his book by introducing an 18th-century brigadier general in the British Coldstream Guard, a 19th-century Ottoman sultan and a ground-breaking American jazz singer of the 1940s – and challenging us to ponder what might connect them. As it turns out, the secretions of tiny, six-legged critters went into products that either adorned these three humans or contributed to their achievements. Melillo’s point, of course, is that even if insects give some of us the willies, we humans are all intertwined with and even dependent upon them, oftentimes in fascinating ways. Pulitzer Prize-winning author Elizabeth Kolbert observes: “Insects turn up everywhere, including throughout human history. Lively and engrossing, (Melillo’s book) shows that bugs matter every bit as much as generals and emperors.”

When we bite into a shiny apple or enjoy a spoonful of strawberry yogurt, listen to the resonant notes of a Stradivarius violin or watch fashion models strut down a runway, receive a dental implant or get a manicure, we are mingling with the creations of insects.

from The Butterfly Effect: Insects and the Making of the Modern World

Copyright © 2020 by Edward D. Melillo, Alfred A. Knopf, all rights reserved

The Forests of California

by Obi Kaufmann

(Heyday, $55, 640 pages)

I’m practically drooling over an advance copy of this thick, lavishly illustrated tome from Oakland’s own writer, artist and naturalist Kaufmann, whose “California Field Atlas” spent many weeks atop the Bay Area best-sellers charts in 2018. To be published Sept. 8 as the first of a trilogy on California lands, this marvelous, idiosyncratic exploration of our forests past and present, jammed with charts, diagrams and stunningly beautiful watercolor drawings of trees, birds and forest wildlife, is by turns lyric poetry and crystal-clear, fascinating science. In a series of notes to readers on how to approach the book, Kaufmann says it is neither a tourist guide nor a textbook, but a “field atlas” of his own invention, an activist guide designed not to give us the “what” or the “where” but the “how” of things. His aim is to raise our level of “geographic literacy.”

I’ve come to realize there is a sublime experience that is revealed when the artist and the scientist alike come to nature with acute perception and invested passion. What is revealed is a delicate process of communication from the more-than-human world. This communication, this story, has within its mystery the solutions to unraveling some of the problems that are affecting every ecosystem, globally, regionally, and locally. The key to the mystery may be understanding not only the information itself, but how humans process information at all.

from The Forests of California

Copyright © 2020 by William Kaufmann, Heyday Books, all rights reserved