Amid the backdrop of coronavirus, issues are being raised around the world on the viability of arts institutions, the survival of businesses, and the racist systems that limit people of color. Nothing is as it was, or will be.

On June 8, a band of theater professionals of color calling themselves The Ground We Stand On released a list of demands and a statement addressed to the white theater world in New York. The letter described collective marginalization, tokenism, racism and exploitation of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and people of color) performers, directors and all levels of crew positions in spaces long dominated by old, white people.

The letter was signed by the likes of Issa Rae, Viola Davis and Sterling K. Brown, and the demands, not requests, reflect systemic issues that prevent BIPOC, and theater itself, from thriving.

The Bay Area is home to literally hundreds of theater companies, dance troupes and art collectives representing the experiences and cultures from all over the world. The convergence of the coronavirus and #BlackLivesMatter has borne many conversations, articles and political discussions on the disparities in this country.

While employment, health care, racism and immigration remain at the top of the list, the theater world has also been called out for its flawed approaches, or lack of approaches, to diversity and equity. In early July, a Bay Area theater leader decided to step up by stepping down.

Last month, the San Francisco Chronicle reported that Jon Tracy, the artistic facilitator of the Berkeley-based company TheatreFirst, was looking for a successor. Tracy, a white man, “demoted” himself, the article states, to purposefully create a space for BIPOC leadership in a field where those opportunities are perpetually lacking.

Lacking is generous. Multiple coalitions over the years have published statistical reports on the representation of BIPOC and gender disparity in the performing arts.

The Dramatists Guild of America has published two reports, called The Count, that survey the demographics of playwrights with plays produced across the United States. The most recent one, The Count 2.0, was published in 2018. It examined six seasons from 147 established theaters across all 50 states, dividing results up into regions.

Nowhere in the U.S. did women or BIPOC playwrights dominate or even break 50%. In some regions, representation for BIPOC writers was as low as 8%.

For over a decade, the Asian American Performers Action Coalition has published the “Ethnic Representation on New York City Stages” report, which “tallies the ethnic makeup of cast members from every Broadway show” from that annual season, in addition to “productions at the sixteen largest non-profit theatre companies in New York City,” as stated on the coalition website.

Data from the most recent report for the 2016/2017 season indicates that 66.8% of roles were performed by white actors, with African Americans representing 18.6%, Latinx performers 5.1% and Asian Americans 7.3%. The remaining 2.3% are distributed among Middle Eastern, American Indian and Indigenous actors. This is actually an improvement from the first report from 2006/2007, where white actors filled 85% of roles.

“That’s literally why we started this company,” said Rodney Earl Jackson Jr. Jackson and Marcelo Javier Pereira are the co-founders and co-artistic directors of the San Francisco Bay Area Theatre Company, or SFBATCO (pronounced Ess-Eff Bat-Co) for short. Both grew up in San Francisco and attended what is now called the Ruth Asawa San Francisco School of the Arts. They both went on to prestigious performing arts colleges (Carnegie Mellon and Syracuse, respectively), and moved to NYC after graduation. And both found that eking out a living in the theater world as queer men of color was less glitzy than Broadway would imply.

“Bay Area boys gone off to school to the East Coast to get BFAs and live the Broadway dream. But whose dream is this? We don’t see a lot of opportunities that aren’t aligned with Black or Latinx leadership,” Jackson said of his auditions in the Big Apple. “We either gotta have Lin Manuel up there, or a fierce black female playwright. Or it’s gonna be a jukebox musical.” Jackson has performed in, among others, productions of “Book of Mormon” and “Motown: The Musical.”

Pereira, who identifies as mixed race, changed his major from musical theater to acting after being told the theater world would only see him as a Latinx performer.

“It was exactly what I expected,” he said. “You’re either in a play about the systemic oppression of your people, or it’s about a Latin pop star. There are no stories of BIPOC joy or BIPOC people falling in love, or maybe the fact they’re just people. ‘You look like that, so I’m gonna send you to these pigeonholed things.’ Any story that has BIPOC in it — that is a good thing, that is technically progress. Having our faces [in a production] makes tons of profit, but the ones making money are not us.”

So rather than waiting for someone to make space for them, they took it. Still in NYC, they filed the paperwork for their San Francisco theater company and applied for grants. After receiving a three-year incubation grant from San Francisco’s African American Art & Culture Complex, both men moved back to the Bay Area in 2015 and got started.

Pereira calls the early years “rough and crunchy,” with pained laughter. They focused on winter shows because that was when their performing peers would be home for the holidays. They received a bad review in the San Francisco Chronicle for a play they produced called “One Googol and One,” a take on Scheherazade’s many tales. The mantra of their “crunchy” days: beg, barter, steal. They pressed on.

Besides the 10 board members (Jackson and Pereira are two of them), the company core comprises of six people, and every one identifies as a person of color. The company’s most well-known show is “I, Too, Sing America,” which Jackson describes as “BIPOC excellence.”

The issues don’t stop at downstage, or in the wings. Audience demographics also show that plays and musicals that are predominantly cast with white people are mostly attended by white people. Pereira describes even attending “Hamilton” as an audience member as being “one of the only ones of me.”

“At the end of the day, we’re talking about systemic issues that run so deep in our country,” Pereira said. “Part of the bigger problem as it relates specifically to the arts, though not exclusively, is exposure. Black and brown children in this country are not exposed to the art we do. It’s not because they’re dumb, it’s financial.”

In 2015, Theatre Bay Area, the local authority in performing arts coordination, commissioned and released the “The Arts Diversity Index: Measurement of and Impacts on Diversity in Bay Area Theatre.” The index examined “500,000 attendance records of theatergoers in the San Francisco Bay Area from 2006 to 2012” and the demographics of 25 local theater companies across size, age and diversity to further examine theater participation and audienceship.

The index also cross-referenced the general population, by income, age, gender, education and even political party using statistical data from five Bay Area counties. The saying goes “nobody goes to the theater.” According to the index, the nobodies still attending are mostly old white guys.

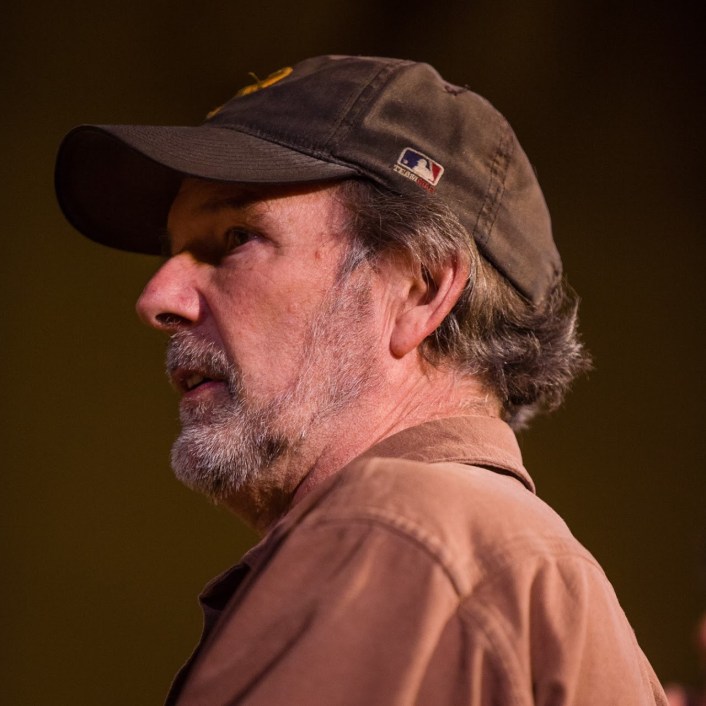

David Parr currently serves as the chair of City College of San Francisco’s Theatre Arts Department, and he is well aware he is an old white guy. He’s taught at CCSF for decades and has witnessed how theater can enrich the lives of his students. But with classes going virtual, he worries students can’t contract the theater bug via Zoom, or understand how to bring it to a stage, once theaters are open again.

“We can’t teach what we teach right now,” Parr says over Zoom. “We can’t give students the experience of learning theater. Theater is ephemeral; it exists in the moment. When there’s no public, it’s an arthritic approach to the craft.”

Parr has taught full time at CCSF since 1999, after years of part-time teaching and pursuing his dreams as a stage actor, thinking teaching was “not really what I wanna do.”

Forty years from his first class, he’s still there, for now. Besides Parr, the department has two other faculty members. All three are white, but many of their students are not. Equity in theater education is a preliminary step to equity on the stage, but the process to change this, unlike Tracy’s self-demotion, is much slower.

“It’s a very ponderous process.” Parr said. “I’ve been there for 40 years, and until I step aside, there isn’t room. We can’t just say, ‘I’m gonna retire, and let’s find a young Black woman to replace me.’ There is no affirmative action for that right now.”

But as budgets and revenue (Broadway not included) dwindle year by year, so do these kinds of positions. A white leader creating space is a step in the right direction, but what if the space isn’t there?

“CCSF is shrinking, they won’t replace me when I retire,” Parr says.

Before Parr retires, he is also stepping down from his extracurricular activity as the creative director and stage director of California Revels, a 100-strong performance company best known for their holiday pageant shows that invoke cultures from mostly the British Isles and parts of Europe.

Parr, not unlike Tracy, will have stepped out of his role July 31, with the expressed desire to have someone young and non-white carry the theatrical torch. While the company did have a number of BIPOC performers and had performed shows around non-white religious celebrations and rituals, they are few and far between.

“Revels need to reimagine itself,” Parr said. “It needs someone much younger to come in and move it forward. Ideally that is someone sensitive to equity, willing to risk more than I was, not invested in what it has been. Someone ambitious enough to move it forward. It’s not about another me.”

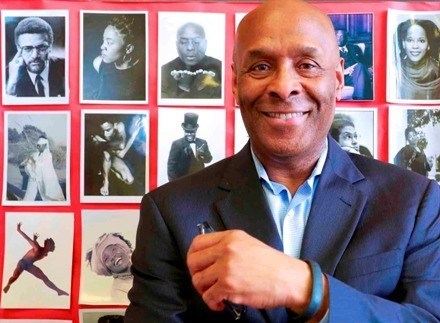

Thomas Robert Simpson started his theater and performing arts company, AfroSolo Theatre Company, because of a birthday party.

The Nashville native had studied for a master’s in psychology, but the theater bug’s infection was too much, and he looked toward bigger cities where he could pursue more opportunities. He flew to San Francisco on a now-defunct airline special: $49 from Atlanta to San Francisco. When he arrived, the weather was terrible (it was January). But after three days, the fog parted, and Simpson saw what every other San Franciscan sees: the misfits, the bold creatives, the inexplicable meteorological shifts.

He returned to Nashville and started planning his move to S.F. — just for a year, then maybe on to Los Angeles. He never left, and in 1991, he threw himself a birthday party with a group of Black artists and performers. It was so popular, his friends wanted another in 1992 — and 1993. By 1994, these coordinated “festivals” of solo performers across multiple mediums had become AfroSolo.

“The whole world is a stage. When I started, there was not a Black theater company doing what I was doing,” which according to Simpson was to “showcase Black artists telling our stories from our points of views: male, female, gay, straight, old, young, disabled.”

In its 26th year, AfroSolo’s original 2020 plans have been canceled. Simpson had planned to produce a show with formerly incarcerated men in April. Now, the plan is to collaborate with artists in home-studio settings for a fall show, maybe in October.

“We’re just figuring that out,” he says. “This whole COVID thing just threw us all.”

Simpson has seen The Ground We Stand On’s “We See You, White American Theater” document, and appreciates the demands and sentiments within. He’s been around too long for doe-eyed optimism to say whether it, or the actions of people like Tracy, will change things.

“The proof is in the pudding.” he said. “It’s too early to tell right now. I don’t know if it’s the flavor of the moment or if it’s gonna be a baked cake. I hope it’s gonna be a baked cake. I don’t know if this is real. It sounds like a good step if power is really changed.”

Parr is of a similar mind.

“We’ll know in a year or two how successful this transformation has been when productions begin again, if there are diverse ensembles and productions and if the diversity is comfortable for them, not just ‘checking off the boxes,’” he said. “The time of COVID is a luxury because no one can be busy doing what they do, they can [practice] self-analysis.”

The future doesn’t look good, but then again it never did. Parr laughs before musing, “Anyone optimistic about the future of theater is a fool; it’s always dying.”