Prepare to be toppled by Black riders on horses — especially the majority of people claiming to know the complete culture and history of equestrians in the American West.

Often, public awareness and scholarly education about cowboys, rodeo riders and professional, competitive horse riders is blindingly white. Or, if it includes people of color at all, it tacks on brazenly racist depictions of war-painted Native Americans that demean Indigenous people.

The presence of Black equestrians in the West is largely overlooked or forgotten. Only within the last 10 years have Black cowboys gained attention from the likes of BBC Newsand Smithsonian magazine.

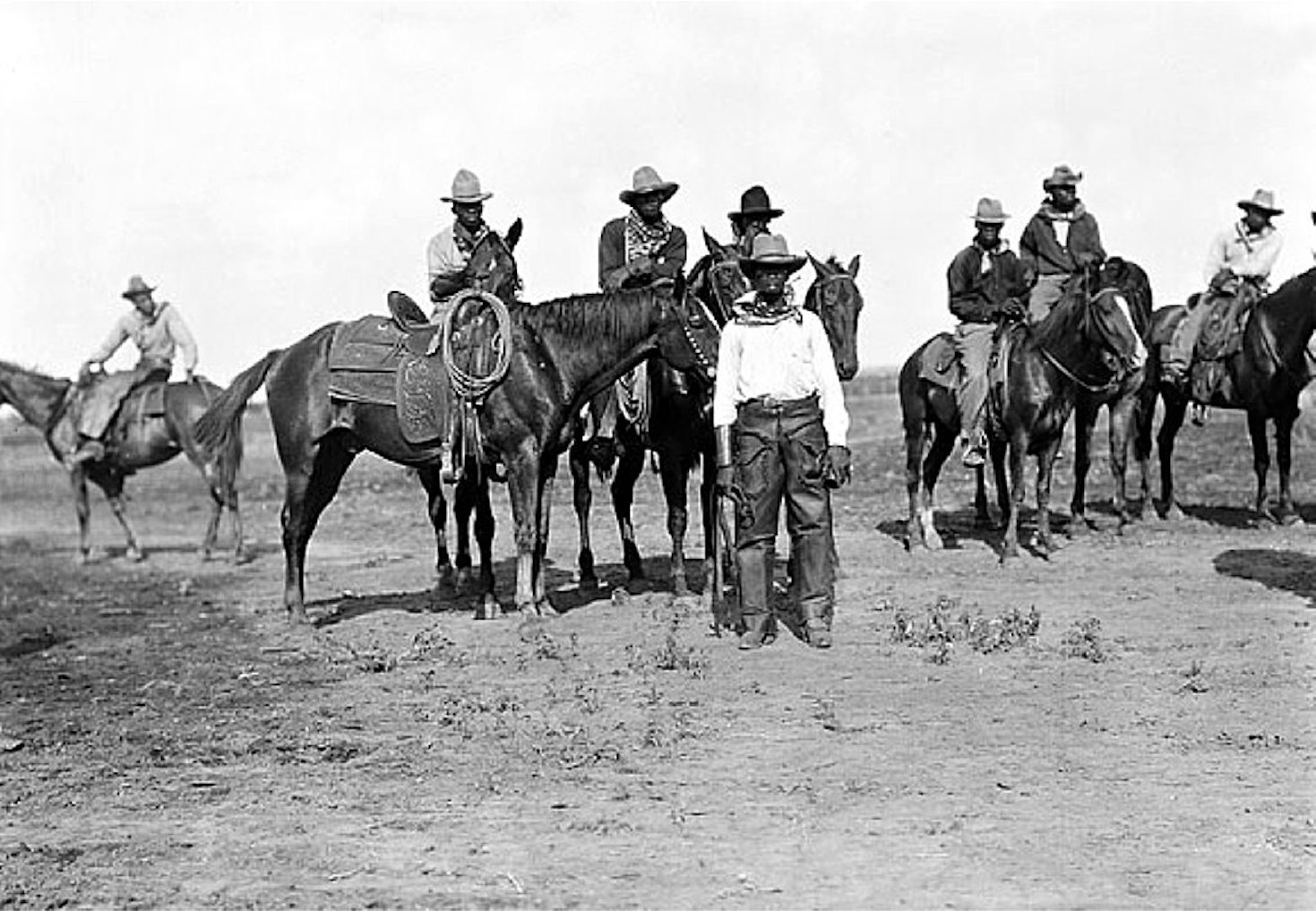

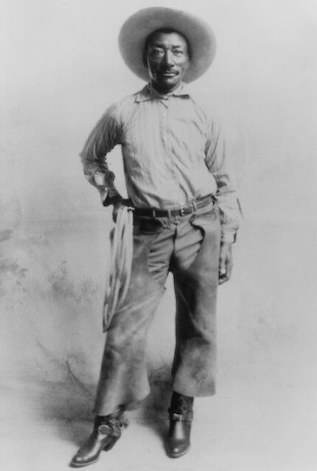

It is estimated that in the mid-1800s, 25% of the Old West’s 35,000 cowboys were Black.

In a 2017 article titled, “The Lesser-Known History of African-American Cowboys,” former Smithsonian reporter Katie Nodjimbadem’s subtitle reads: “One in four cowboys was black. So why aren’t they more present in popular culture?”

That question posed in a phone interview to Oakland Black Cowboy AssociationPresident Wilbert McAlister, draws immediate response: “Caucasians, Black people, Asians and all others don’t even know the original meaning of the word ‘cowboy.’ I want the public to know the word cowboy is a slave term.”

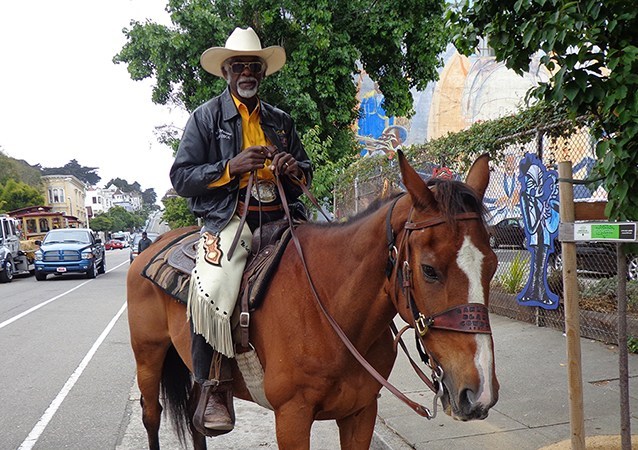

McAlister, 79, has been involved with the Oakland Black Cowboy Association since 1999. The nonprofit organization is best known for the annual Black Cowboy Parade and Festival and community outreach to educate people about the contributions of Black cowboys in Oakland and Western American history.

A native of Madera, McAlister takes special pride in his grandfather’s legacy as a rancher. He says history left out of books and films fails to teach about Black cowboys who built towns, moved cattle, respected mankind, rarely carried guns — or thrilled rodeo enthusiasts with impressive skill and style.

It wasn’t until 1972 that a posthumous tribute came to renowned rodeo athlete Bill Pickett, 40 years after his death, when he was made the first Black honoree in the Rodeo Hall of Fame at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City.

“During slavery — which I’ll have you know didn’t end in the 1860s and continues today — they had house boys and field boys,” McAlister said. “They had another boy to take care of the horses they called a ‘cowboy.’ Black cowboys couldn’t marry or go to church with the white folks.”

Which doesn’t mean McAlister resists the term. He remembers four young white boys taunting him by yelling racist words. “I was dressed in my finest cowboy clothes and they yelled (the N-word) and ‘cowboy’ at me,” he said. “They were trying to insult me, but I was going to tip my hat to them in a country way because they had said ‘cowboy.’”

Leaping forward in time to 2020, McAlister says canceling this year’s parade because of the coronavirus pandemic was devastating.

“It’s affected our budget 100 percent,” he said. “That’s the biggest day we have of the year to produce revenue. That’s when we do our mission to provide educational information to the public about Black cowboys and Black cowgirls.”

The relevance of the missed opportunity intensified after the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis on May 25. “After George Floyd got killed — well, growing up, we knew about Emmet Till,” McAlister said.

“That 14-year-old boy was lynched in 1955 by a mob after talking to a white woman in a store. We were told as Black kids how to talk, who to talk to. Yes sir, no sir, hold your head up. I had to teach my kids. As an adult, I had to watch my p’s and q’s; tiptoe on the line; not speed on the highway.”

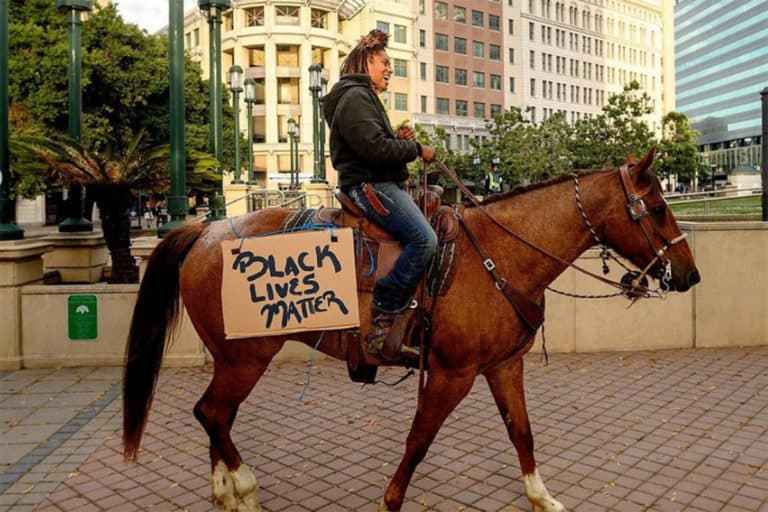

The tiptoeing is over in 2020. That fact is known to anyone awed by the site of professional equestrian and business owner Brianna Noble astride her 17-hand horse, Dapper Dan, while leading a massive crowd of Black Lives Matter protesters through downtown Oakland on May 29.

The powerful image of a Black woman rider on a large Appaloosa gelding — a handwritten “Black Lives Matter” poster pinned to her saddle — garnered national attention from The New York Times, Vogue, The Guardian and major radio and television outlets.

A GoFundMe campaign launched to support Humble, a program she founded and operates that offers equine programs to underprivileged and marginalized communities, has raised nearly $64,000 toward a $100,000 goal.

McAlister says he does not know Noble personally or professionally, but is well aware of the iconic imagery her urban ride represents. “I know about this sister, and I’ll say that horse had to be really well trained because they get nervous around big crowds,” he said.

“I’m glad they made note of her, although there’s nothing new about a Black horse rider. White folks just have to wake up. More people are conscious, but when that policeman killed that boy [George Floyd] on that camera, he had his hand in his pocket and he looked like, I don’t give a damn. Now, more caucasian people know what’s going on, but they should have known ages ago.”

Noble says she’s not as well-versed as experts on the history of Black riders and therefore chooses her words carefully. “I’m a believer in people sticking to what they’re good at,” she said.

“I’m passionate about and have a good understanding of the need and ways of finding a safe space for young people of color in the equestrian community. It can be hard and challenging to go into a world where no one looks like you and everybody stares at you. What do I believe I can do to change that? I want to bridge the economic gap for those kids so we can see more brown faces in the equestrian world.”

As a girl at 5 or 6 years old, Noble aimed to become the first African American to show jump at the Olympics.

Beezie Madden was an early heroic figure that helped Noble look past the singularity, otherness and outright stares she endured as a person of color while training at Skyline Barns in Oakland.

After attending Oakland School for the Arts as a teen, she jumped to enroll in junior college courses in veterinary technology. Today, as a 25-year-old mother married to professional rider Adolfo Gutierrez, Noble says the childhood Olympic dream dissolved, but a passion for bringing inner-city youth into the horse world remains.

“If you gave me $30,000 right now I’d put it into my program with Humble,” Noble said. “I’m in Briones, and it’s 20 minutes from Oakland, but I want to go into Oakland and Richmond and make the program more accessible.”

Noble mentions locations she plans to or would like to hold programs: Oakland City Stables, a 7.2-acre equestrian property off Skyline Boulevard owned by the city of Oakland, and Sequoia Arena, a corral in Joaquin Miller Park.

With funds to provide transportation, and thinking long term, she allows her vision to expand: “I had a 130-acre ranch in El Sobrante that I lost after I asked the landlord if I could run the program there. He didn’t like the idea of kids running around. He tripled our rent and gave me 30 days to sell everything I owned and get off the property. I’d love to get that actual property back. I hope with the recent notoriety I can go to the land’s actual owners in China and buy it from them.”

Horseback riding, Noble says, fosters leadership skills, provides a sense of family and puts up a mirror to a person’s soul.

“This beautiful creature allows you to look within yourself and make a change,” she said. “If I tell a child they need to calm down, that the way a child is behaving is inappropriate, they say ‘Huh, who are you?’ But if I say — when they’re around a big, powerful animal — to go touch it, that teaches self-control without human judgment. Horses are an amazing teaching tool.”

Asked if her ride can be a teaching tool to reach adults and inspire the dismantling of systemic racism in the United States, Noble says hope is hard to find. In recent interviews, she has said Black people experience racial hostility every single day — in the workplace, society, classrooms and basically, everywhere.

“There’s not much you can do about it,” Noble said. “This is the first time in history I’ve seen where you can even have this conversation and not get your ass burned. You associate with an idea or say something on a ranch and — it’s messed up, but you won’t get work. You won’t be invited back to work at ranches. People have come up and tried to pet me like I’m an animal. If I say ‘No, that’s not appropriate,’ I may not be asked back to work there. There’s no governing body in the equine world. All you can do is suck it up. Things are changing, but there’s no place to report a violation in the horse world.”

Following Floyd’s murder, frustration finally roiled Noble’s usual calm, steady state. The response to her ride after photos and videos went viral on social media was a surprise.

“There’s nothing that could have prepared me for this attention,” she said. “The night before, I was just pissed off. Ten years after Oscar Grant happened; here we are again. I just thought I’d get notoriety in Oakland, with local papers. I thought it might change the narrative in Oakland. It’s gone to every large publication and magazines in France, Germany, Australia, everywhere. I don’t like the fame, but it’s put me in a place where I can brush aside the attention and say ‘Hey, here’s what we can do for society and the kids.’”

What Noble can do if large companies begin to fund her programs is make the horse world more accessible to people of color.

Importantly, Humble will also launch a study into the impact of equine experiences on inner-city youth who have suffered trauma.

“I want measures and data we can share,” Noble said. “To grow the programs, companies we ask for support will want impact statements and measures they can see. To have a few years of statistics, we hope the study will support ours and other programs in other parts of the country so they can do what we want to do.”