You know that saying, “The more things change, the more they stay the same.” Few might agree right now, given the Bay Area, the United States and the whole world have been impacted over the last six months by the coronavirus pandemic.

Masks of varying materials, designs and cleanliness are everywhere; the tan lines this summer are going to be insane. Millions of Americans are fed up with stifling their breathing with N95s and avoiding their loved ones — to the point that angry, maskless citizens have shown up at state capitols with guns to demand the freedom to show their chins to the world, and also get a haircut. This is an unprecedented, spontaneous disease out of nowhere! Or is it?

It, in fact, is not. According to Brian Dolan, a professor at UC San Francisco School of Medicine with a Ph.D. in history and philosophy of medicine, a flu outbreak has been anticipated by experts for over a decade. The medical world just didn’t know it would be this virus.

“When you hear claims in the media that we didn’t know, that nothing was done — a lot of the stuff coming out of the White House — you look to see if that’s true,” Dolan said. “[Dr. Anthony] Fauci was working on this 25 years ago, was warning of this 15 years ago. None of the people in medicine think that this is an unexpected or new thing,” Dolan said.

In Dolan’s paper, “Unmasking History: Who Was Behind the Anti-Mask League Protests During the 1918 Influenza Epidemic in San Francisco?” published in May, Dolan draws on archival documents and research from the board of health, the San Francisco Chronicle and the Board of Supervisors to identify and analyze significant parallels between the pandemic we are living through and that of 100 years ago, when San Francisco was devastated by the Spanish influenza and more than 3,000 residents died. For comparison, a total of 500,000 Americans died from the disease between 1918 and 1920.

Back in 1918, San Francisco was a bustling West Coast city with a population of about 500,000. President Woodrow Wilson was dealing with the ending and aftermath of World War I when the first cases of the influenza were reported in the United States in mid-1918. San Francisco reported its first cases that October.

PBS speculates the postwar euphoria and the collective desire to party in the streets contributed to an infection sprawl, much like the dozens of music festivals, parades and outdoor events citizens would have attended this spring and summer had measures not been taken.

The city would not be caught with its pants around its ankles or masks around its neck and, with recommendations from San Francisco City Health Officer Dr. William C. Hassler, acted as swiftly as it did this March.

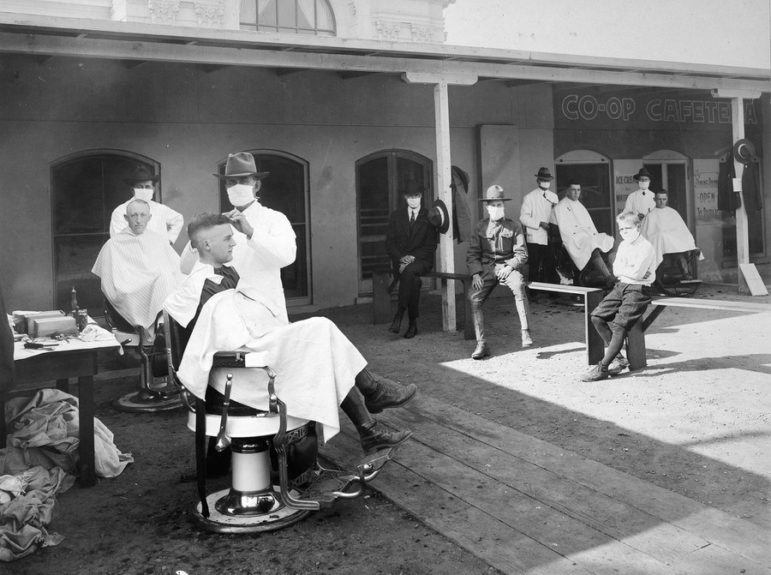

Many of the measures currently in effect were put into place in 1918: San Francisco closed bars, restaurants, theaters, churches and schools (with no Zoom alternatives). Social distancing was in effect, in practice if not in name. And of course, the harbingers of sweaty upper lips and bad breath arrived: the masks.

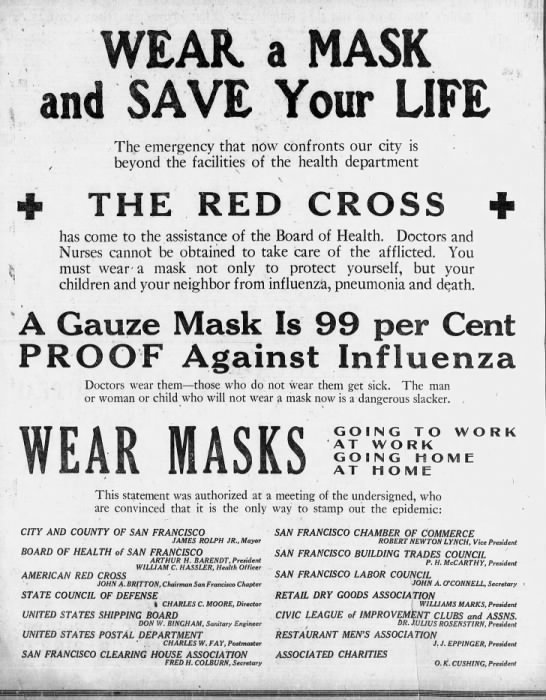

Unfortunately for citizens at the time, masks in 1918 were, if you can believe it, even worse. Rather than Area 51-level gas masks or repurposed dish towels, people had to make do with what was essentially a wad of medical dressing. Four layers of gauze couldn’t have been comfortable to wear all day, and we know now gauze is far too porous to mitigate much.

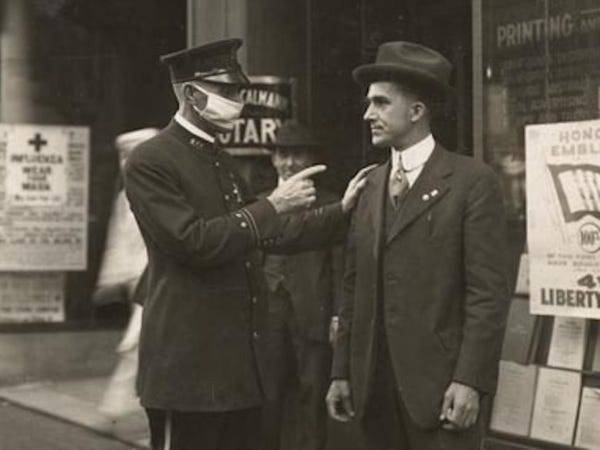

The Red Cross, in a public-service announcement from the time, called anyone who didn’t wear a mask a “dangerous slacker.” Apparently, hundreds of San Franciscans were jailed and fined for free-nosing it, and one man was even shot by a health inspector for his ruddy-cheeked rebellion.

It would seem all was well in the City by the Bay, as cases and deaths following these “stay at home” measures dwindled significantly. After four weeks, on Nov. 21, 1918, Mayor James Rolph Jr. decided the coast was clear, and the masks could come off.

Archival reports from the San Francisco Chronicle detail a jubilant scene of noses breathing the open air. They even compiled a collage of locals beaming and unencumbered by their “muzzled misery,” as the paper phrased it. As happens today, conflicting information was rampant.

“You look at medical journals of the period,” Dolan said. “And you start to see sources of controversy, people citing opinions, selective misreading. You start with medical opinions, then Board of Supervisors’ publications, then the newspapers. It depends on what you want to believe or the position the person wants to defend. Masks can be effective; the problem is that they’re hard to enforce. It’s a behavioral issue.”

Birthday parties, bar-hopping and barbecues may not sound like behavioral issues, but spikes in cases have been linked to activities like them. This July has been a testament to the perils of reopening prematurely. In the weeks following masks off in 1918, more than 2,000 cases were reported. The hubbub of holiday shopping was no help, and a week before Christmas, the Board of Supervisors voted in favor of reinstating the masks.

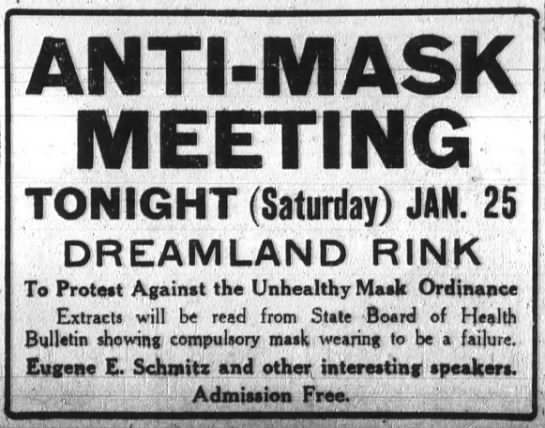

This decision would further the political legacy of Mrs. E.C. Harrington, the founder and president of San Francisco’s Anti-Mask League.

Harrington was, unlike many anecdotal anti-maskers in the news, highly educated and accomplished. She was a staunch suffragette, to the point she essentially strong-armed her way into being the first woman registered to vote in San Francisco. She advocated for labor unions and legal representation for the poor.

Despite a sexist law school environment and unfairly grueling exam, she passed the California bar and became a successful lawyer with growing political ambitions. These ambitions included a seat on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, which she never attained. The rest of her league’s cabinet were also women, though it is difficult to speculate on the optics of this gender divide and if it meant anything at the time.

By no coincidence, Harrington had long been a political ally of Rolph’s predecessor, Mayor Patrick Henry McCarthy. Dolan believes the priorities of either side were not entirely about public safety.

“If you were to imagine who was anti-mask at the time, you imagine business people or skeptics of medicine,” Dolan said. “There isn’t one perspective on why masks are a problem: It’s medical, it’s economic, it’s personal freedom. When the second mandate came, this very specific group formed. The people like Harrington represented laborers. They were a voice that was on the opposite side of the spectrum of the business leaders, different unions. The group was less concerned about masks and more anti-mayor. There were personal political agendas involved.”

Co-opting an arbitrary symbol for a partisan issue? Unheard of.

By the time Mayor Rolph publicly asked citizens to re-don their masks on Jan. 12, 1919, dozens of people were dying a day from the flu, according to figures from the San Francisco Examiner. But as we know today, facts are not enough sometimes.

Hundreds would gather to protest the masks later that month while denouncements of the masks and, the flu itself, continued. We can only wonder what kind of memes would come out of that time. Hassler, like Fauci, was discredited and criticized, and even received a bomb threat for his faith in the odious face muzzles.

Mayor Rolph ultimately backed off from social distancing and mask measures, and repealed Ordinance 4758 in February 1919. This decision, based on Dolan’s research, appears to be more based on civil unrest and the actions of neighboring Oakland and other California cities rather than concrete medical evidence that masks were ineffective.

Political agendas are still being wielded today even after the deaths of almost 140,000 Americans and surges overwhelming hospitals from coast to coast.

“It’s how you turn a public health campaign into a political campaign,” Dolan said. “It devalues it as a simple device to control a situation that’s out of control. Instead of letting it do its job, it becomes an ideological term. It’s having an impact on how this pandemic is being framed. We are doing a much worse job now than we were in 1918. Part of it is down to a lack of scientific literacy. You’re listening to the wrong person on the risks” — i.e., the host of the “Love Connection,” or anyone in Florida right now.

When your president openly disagrees with and undermines the nation’s leading medical experts, when your secretary of education all but condones the deaths of thousands of children for the sake of classroom learning, and when the victims are disproportionately from Black, Latinx and immigrant communities, the pandemic does take on political urgency.

This is about so much more than a sweaty bandana or tye-dyed cotton covering.

Now, as back then, political agendas have been foisted onto a symbol of public health that is simply there to prevent the transmission of airborne germs.

In San Francisco, however, we seem to have gotten the message; our mayor has remained steadfast in keeping masks on and gatherings closed, and has yet to be seen at a boxing match barefaced like Mayor Rolph was. We have had far fewer deaths and cases overall, and have blessedly avoided any spikes like most of the country is experiencing now.

At the time of publishing this article, the city has reported 53 COVID19-related deaths and more than 5,300 cases. Sometimes (like now) a mask is just a mask, and you should wear one.