Twenty-eight of the 38 California counties with surging cases of COVID-19 report that they are attempting to investigate everyone infected and trace everyone they expose. But at least seven counties aren’t, and another one is asking all people with the virus to notify their contacts themselves.

A CalMatters analysis of contact tracing in California shows that the scope varies considerably from county to county, from thorough to minimal. Contact tracing is considered an essential tool in reducing the spread of COVID-19 by notifying people who have been exposed.

Most of the 38 counties on the state’s watch list, including Los Angeles, San Francisco, Fresno, Kern and San Diego, told CalMatters that they are interviewing all infected people and attempting — often with limited success — to notify everyone they’ve exposed.

But seven counties — Orange, Riverside, Contra Costa, Santa Cruz, San Joaquin, Sacramento and Yolo — said they are triaging their efforts because they have so many cases and testing lags behind. Collectively those counties have almost 100,000 residents infected with the coronavirus.

Six of those seven counties aren’t interviewing all people with the virus, only those who are considered high-risk or recently tested positive. Four are only notifying some contacts of infected people, such as the elderly or people with health conditions.

Two counties, Kings and Mendocino, did not answer CalMatters’ questions about their contact tracing.

One county, Merced, has the least amount of tracing: Since late June, its health department hasn’t notified contacts except the infected person’s workplaces and health care providers. Instead the county asks all sick people to tell their own friends and others that they’ve been exposed.

Orange County also is telling most residents with the virus to warn their own contacts.

What Merced and Orange counties are doing “is by no means contact tracing,” said Perry Halkitis, dean of the School of Public Health at Rutgers University and the principal investigator for New Jersey’s contract tracing program

Halkitis said that while it’s polite for infected people to inform their own contacts, it cannot replace trained staffers notifying them.

Local contract tracers are like coronavirus detectives: They interview infected people to collect the names of friends, relatives and others who have been within six feet of them for more than 15 minutes. Then they request their phone numbers and emails, and advise them to get tested.

Under the Newsom administration’s orders, counties are required to investigate positive cases and then trace and notify their contacts when they reopen businesses. But as infections surge and counties are overwhelmed, state officials are not cracking down on them or telling them to improve their tracing.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that among the “core principles” that “must always be adhered to” in fighting COVID-19 outbreaks are “work(ing) with a patient to help them recall everyone” they’ve been around and then “warning these exposed individuals of their potential exposure.”

But seven counties told CalMatters that they are not trying to inform contacts of all infected people because their resources are stretched thin. Their efforts also are hamstrung by delays of a week or more in virus test results, which means they are notifying people too late.

“Even a very robust contact tracing program in every single county will have a hard time reaching out to every single case,” given the rate of transmission, said Dr. Mark Ghaly, the state’s secretary of health and human services.

What counties are doing

Reaching 38 on Tuesday and growing weekly, the state’s watch list contains counties where cases and hospitalizations exceed state benchmarks.

Despite being the nation’s most populous county, Los Angeles County is attempting to trace contacts of everyone infected. Since April, its tracers have interviewed 110,000 infected people and 38,000 close contacts, according to the county’s dashboard.

The county reports that it’s reached practically all positive cases and around 80% of their provided contacts. But only two-thirds complete the interview process, so the county is offering $20 gift cards to anyone who does.

San Francisco County, with more than 6,000 confirmed cases, also is attempting to notify all infected people and their contacts. According to its dashboard, San Francisco is reaching 81% of cases and 84% of their contacts.

Glenn County, a rural county in the Sacramento Valley, has a population of about 28,000 and 280 coronavirus cases. A spokesperson said its 15 case investigators and contact tracers enable them to reach every case and close contact.

San Francisco, Glenn and at least 22 other California counties are meeting the requirement they agreed to in order to qualify for reopening — 15 contact tracers per 100,000 residents, according to a CalMatters analysis of county agreements.

However, at least 11 counties have not achieved the requirement for tracers, including Merced, Fresno, Orange, Sacramento and Santa Clara counties.

Ghaly said counties in May had to demonstrate credible plans to build up. “This was an opportunity to prepare around contact tracing, not necessarily to have it all there,” he said. The state says it has about 10,000 tracers who can help counties but many have not been deployed.

But some counties still aren’t meeting those requirements.

Orange County needs 477 contact tracers to meet its requirement, according to its May agreement, but currently has only 182. Jessica Good, an Orange County Health Care Agency spokeswoman, said that state officials are aware of its situation.

With 34,833 cases of coronavirus, Orange County “frequently” relies on infected people to reach out to their own contacts, said Mark Meulman, acting director of the health agency. He said Orange County is focusing on notifying work and household contacts, and usually asks the infected person to inform others outside their home.

The current “level of staffing is not sufficient to keep up with the current level of disease transmission,” Good said. An outside contractor was hired last week to help.

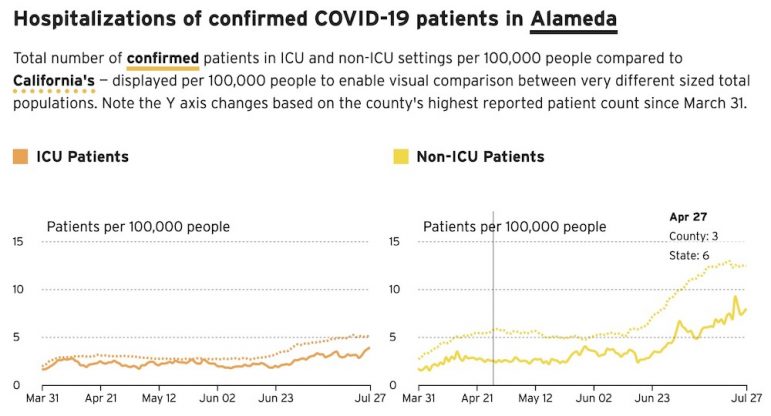

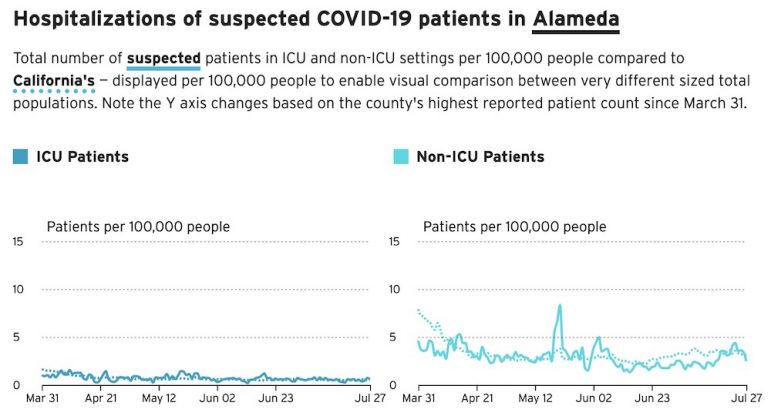

Alameda County in depth

The three other counties that have adopted partial, targeted tracing said they are only informing contacts they consider high risk, such as those over 65.

Halkitis of Rutgers said he is concerned that health officials are using an array of factors to determine who is “high-risk.”

It’s like “you’re measuring a room with twenty different rulers,” he said. In order for contact tracing to work, he said, it has to be uniform.

But when asked about some counties’ minimal efforts, Ghaly said that reaching out to only high-risk people is a wise approach with limited resources, and asking people to notify their own contacts is a “novel and important” tool because it could mean more people get tested and quarantined.

Carolyn Cannuscio, an epidemiologist at the University of Pennsylvania, said contact tracing is not as effective when testing is delayed, so she understands the counties’ dilemma. Someone tested 10 days earlier already exposed many people.

“We should think of contact tracing as just one component of the entire prevention portfolio or cascade,” she said. When one element of the cascade fails, she said, the entire system will no longer be as effective.

Merced County and residents disagree

Merced County Supervising Epidemiologist Kristynn Sullivan said by the end of June they stopped trying to notify infected people’s contacts because of surging cases, understaffing and a high level of general exposure among residents.

While county officials said they are still interviewing all infected people, they only notify their workplaces and health care providers — no friends, relatives or others who were exposed. It has not met its requirement of 42 tracers, but is hiring more.

Merced County Director of Public Health Rebecca Nanyonjo-Kemp insists that what her team is doing qualifies as contract tracing, even though it doesn’t include warning contacts, which the CDC calls a “core principle.”

“We do, for clarity’s sake, do contact tracing. Maybe not in the germane way,” she said.

She added that “we are not doing that (warning contacts) directly” but “there’s a script that we work off of, advising the individuals to advise individuals that they may have been exposed to.”

She said state officials approve of their process but she refused to provide documentation. State health department spokeswoman Ali Bay declined to comment about Merced County.

At least four Merced County residents said in interviews that the county did not ask them about their contacts.

Nancy Valladolid was suffering a severe headache and other symptoms, so she was tested for the coronavirus on July 8 and received her positive results on July 19.

Valladolid said she only received communication from Merced County on July 28. She said they asked where she went, where she worked and what her symptoms were, but not for the names or phone numbers of those she was in contact with.

She chose to quarantine and informed WalMart, her employer, herself. But she thinks the lag and lack of communication could be costing lives.

“If (the county) contacted us, it would help other people not get exposed to the virus,” Valladolid said. “I feel like as soon as you go get tested, they should somehow contact you and see where you were, so people know you were there and they can go get tested, or just have a heads-up.”

Isabel Ayala, also from Merced, said when she tested positive in March, the county placed her under strict quarantine orders. Her family and her sister’s family, as well as her parents, also came down with the virus.

Ayala said the county did not ask her about her contacts.

“I was only asked who I live with,” Ayala said. “Not even where I work. I was never asked for phone numbers, anything. Nobody was asked where we work or if we’ve gone out. They just put us in quarantine.”

Brenda, 21, who didn’t want her last name reported because she fears losing her job, also said she was not contacted by Merced County. She was tested on July 19 after being exposed to someone at work and received her positive results on July 21. She quarantined herself immediately.

She said her mother, Ana, called the county repeatedly to confirm the positive test and ask what they should do. Ana said she finally reached someone at the health department who told them to quarantine but did not ask anything about the patient or her contacts.

“It’s like they aren’t giving this virus any importance,” Ana said in Spanish.

Another Merced County resident, Hugo Garcia, 38, got sick with the virus in mid-June, apparently at an almond processing plant where he works. His mother contracted it, too, and died on July 15. Garcia said county health officials did not ask where he worked, where he went or how he got sick, and did not contact his mother or other family members who were sickened.

Merced County’s health department disputes what the residents said.

Nanyonjo-Kemp said the county back in March had a contact tracing diagram for Ayala’s case, in which its tracers reached out to at least 10 contacts. She also said Garcia underwent an extensive interview on June 20 and submitted a clearance letter that he no longer had symptoms on June 30. She said she couldn’t provide evidence of either interaction due to privacy laws.

Nanyonjo-Kemp acknowledged a lag in reaching out to patients. She said test results due to the backlogs can take seven to 10 days, and then it could take up to three days for the county to learn of a positive case before interviewing them.

“We’re doing the same thing if not a little bit more than” what Fresno County is doing, she said.

But unlike Merced, neighboring Fresno, Madera, San Benito and Stanislaus counties — which all have increasing caseloads — told CalMatters their staffs are reaching out to all the contacts of infected people.

Monterey County has a similar caseload to Merced — 4,140 cases compared with Merced’s 3,763 — and is required to have a similar number of contact tracers. But unlike Merced, Monterey County says it has been tracing everyone’s contacts from its first case in March despite a big surge, and it meets its requirement for number of tracers, while Merced doesn’t. In the past week, it has traced up to 95 infected people per day, and up to 144 cases per day during a surge in early July.

“So far, we’re still at it,” said Karen Smith, public information officer for the county’s health department.

“State has a vested interest”

State Sen. Richard Pan, a pediatrician and Democrat from Sacramento who chairs the health committee, said he understands that counties feel inundated and that delays in test results complicate the process. But he thinks counties should still try to trace and notify as many contacts as possible.

“We are overwhelmed and we’re not going to contact trace everything, but contact tracing also gives us information to know where the infection is coming from,” Pan said.

There are some signs that the state will help local governments more. Gov. Gavin Newsom announced that eight Central Valley counties will receive $52 million in aid, in part for case investigation and contact tracing.

Considering how effective it can be, University of California, San Francisco epidemiologist Dr. Jeffrey Martin said tracing and notifying people’s contacts is absolutely worth the investment.

“The state has a vested interest in the health of all the counties,” Martin said. “It’s not just a local problem.”