At this unique point in history, American society is at the intersection of a global pandemic and an uprising against racist police brutality.

The pandemic and the federal government’s response to it have exacerbated inequality, as more than 20 million Americans are currently unemployed, 28 million are facing evictions, and a disproportionate number of marginalized people, more likely to be low-paid and high-risk essential workers, are coming down with the virus.

Activists say it’s time for real reform, such as reallocating taxpayer funds used for militarized police forces into health care, housing and education.

In the meantime, they are setting up mutual-aid programs both to help demonstrators — with safety supplies and bail money — and to help the most vulnerable people in the pandemic, providing food and medicine, and organizing to protect tenants from eviction.

In that way, 2020 is not too different from the late ’60s: Today’s Black Lives Matter movement is standing up against police brutality like the Black Panther Party (BPP) did more than 50 years ago. The BPP’s Ten-Point Program demanded “full employment,” “decent housing,” “bread,” and “education.”

Behind the scenes, thousands of Black Panther volunteers ran 60-some social programs that fed poor children breakfast, gave away bags of groceries to hungry families, transported sick and disabled people, provided free health care, offered legal aid and drug counseling, and more. Even though much of the reverence, and controversy, around the Black Panther Party centers on its often-armed male leaders — Huey P. Newton, Bobby Seale and Eldridge Cleaver — the hard work of unsung women was the lifeblood of its “survival programs.”

One woman doing such work was Judy Juanita, a playwright, novelist, and poet who currently teaches at Laney College in Oakland. She met Newton and Seale while attending Oakland City College between 1963 and 1966, and joined the BPP at age 20 after she transferred to San Francisco State University.

In 2013, she published “Virgin Soul,” a novel incorporating her experiences as a Black Panther. Her protagonist, Geniece Hightower, has a lot in common with her younger self, and her novel is a fascinating inside look of the early years of the Black Panther Party, as told by someone close to the organization’s center but never in the spotlight. Juanita chatted with me over the phone in 2016 for a Collectors Weekly interview in honor of the 50th anniversary of the Black Panthers.

Here is an excerpt of our conversation:

The Black Panther Party started at Oakland City College in 1966, when you went to school there. What was campus like?

Juanita: It was a convergence of students from many different backgrounds. There was a great mix of ethnicity even then — white, Black and Chinese. The attorney general of the state of California during the Reagan (governorship) administration, Evelle Younger, called Oakland City College “a hotbed of radicalism.” And it was. All kinds of radical groups were there, from Students for a Democratic Society to the W.E.B. Du Bois Club. Young people would hang out on campus — then on Grove Street, which is now Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard — whether they went to school there or not. It was a very exciting scene, with tables lined up and tons of soapbox orators all along the way.

At the time, what was your personal experience of racism?

Juanita: Back then, the focus was on civil rights, like getting Blacks integrated into jobs and public accommodations, etc.

As a young woman, I knew that I faced walls and glass ceilings. While I knew that, I looked at racism as more of problem happening down South and ignored the reality that it was going on here in the Bay Area as much as any place else. Racism has been delineated much more clearly in the past, say, 20 or so years.

Looking back, I do see it in my life. When I was a high school senior, I got the top journalism student honor at my school, Castlemont. My college counselor was white, and her son, who went to school with me, was white. I visited her to ask about getting a scholarship to University of Southern California, which had a great reputation as a journalism school. She said, “You would never be able to get in there.” It was just cut and dried. Meanwhile, her son got into USC. I’m not going to disparage his abilities, but she made sure he got in.

The Bay Area was very integrated in many senses, but it was also very segregated in others. At that time, Oakland was William Knowland’s town. Knowland was a former U.S. senator who became the publisher of the Oakland Tribune newspaper. Thanks to Knowland, back then, East 14th Street was the real estate redline, and Blacks found it very hard to move above East 14th Street until the late ’60s, when there was white flight from the city.

However, the radical edge to Berkeley, Oakland and San Francisco cut into the status quo. You had all these different justice movements here in the Bay Area, like the drug-rehabilitation group Synanon. The Mattachine Society, the movement to prevent gay people from being arrested, started in San Francisco.

What led to the formation of the Black Panther Party at Oakland City College?

Juanita: In Alabama, there was a political party, Lowndes County Freedom Organization, that was known as the Black Panther Party, because of its panther logo. An activist in West Oakland named Mark Comfort took a California delegation to Lowndes County to protect Black people exercising their right to vote after the Voting Rights Act passed in 1965, and he came back with permission to use that logo and name.

The Black Panther Party started in Oakland in October 1966 as an idea for a civilian police patrol. Throughout all the protests and race riots of the ’60s, rioters, civil rights activists, and militants were calling attention to the abuses of police power. The Black Panthers called attention to this abuse in a much more formalized way with their party platform, their activist movement, and particularly their appearance in Sacramento, when 30 Black Panthers carried guns into the state Capitol building on May 2, 1967.

Now, 50 years later, we’re seeing echoes of this sentiment as Black Lives Matter activists draw attention to police brutality.

Juanita: People are seeing we have given the police far too much power in this country. In other democratic societies, the police don’t have that much power. But in the U.S., there’s some sort of alchemy between police power and racism.

When you were part of the Black Panther Party, what were the group’s objectives?

Juanita: The objectives were very clear-cut — the Ten-Point Program. We learned in political education classes that one of the tasks of the Party, the vanguard of the revolution, is to show the people the way. It’s not as though the Black Panther Party alone could stand up and fight the police. It was to show the community we don’t have to let an occupying army come into our communities and take over and slaughter us.

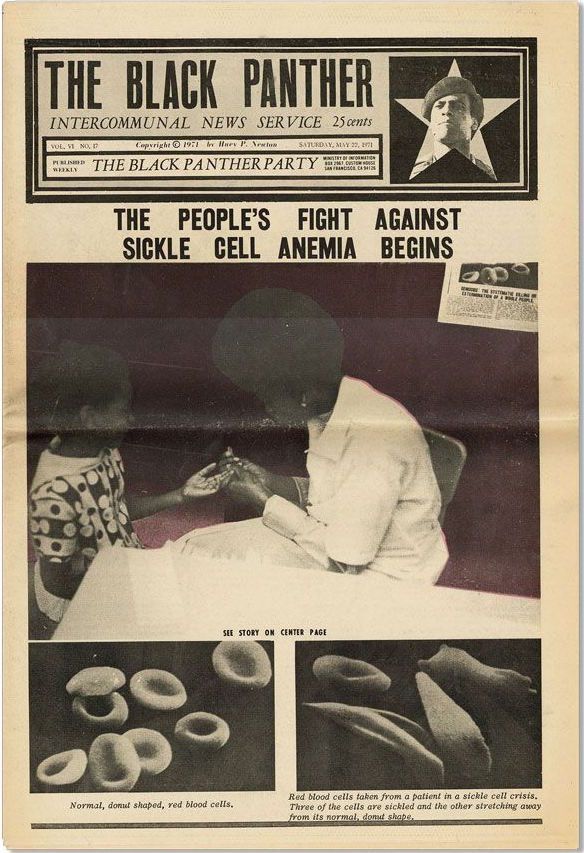

The media put a lot of emphasis on the guns, but there were many community-service programs, like the free health clinic and the Breakfast for Children program. The aim of these social programs was to show the community and the government, “This is what a just society should do.” In a just society, particularly one that is as wealthy as this one, no child should be going to school hungry. Now, the government funds breakfast programs in schools, but it wasn’t doing so back then.

We created more than 60 programs. You know how they would occur? People would go up to Bobby and say, “We have this problem where people can’t see their family in prison.” Bobby would say, “I think that we should have a visitor run. Go do it. You’re in charge of it.” That was incredible and empowering. So the Black Panther Party also started taking families to visit inmates in San Quentin prison.

In the ’60s, people were looking at end-of-the-world scenarios with the atomic bomb and the Cold War. Women who were graduating college were saying, “I’m not going to have any children because I don’t want to bring a child into this world.” That was the most popular type of valedictorian speech at the women’s colleges at the time.

People had a very anti-government sentiment. Instead of being frustrated, people had an attitude of resistance. The government was the antagonist. The American counterculture, we were the protagonists.

* To read the full, original December 2016 story about Judy Juanita’s novel, “Virgin Soul,” and her real-life experiences as a woman in the Black Panther Party, visit Collectors Weekly.