In summary

Forget the notion of a V-shaped recovery. Unemployment leveled off around 16% in May, but a retreat to isolation and the end of some relief funds could lengthen the state’s economic recovery — and deepen inequality.

In late June, it looked like California might be turning a corner in the coronavirus recession. Unemployment had leveled off at a jarring 16.3%, but thousands of waiters, bartenders and hair stylists were going back to work.

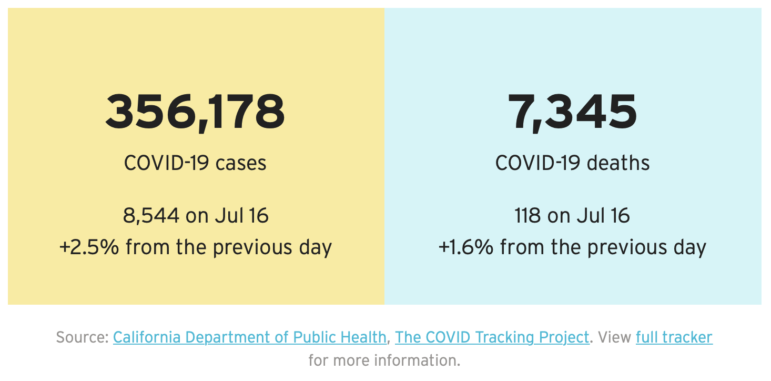

Then came the surge in infections that state officials have been dreading — a record 11,000 new cases on Tuesday alone — and with it, a new wave of business closures.

“We are so sorry,” began the email to customers from San Jose’s Limón Salon this week. “After being open for only one day, we learned that our reopening will be short lived.” With appointments back on hold, the salon said any donations and product sales will go to pay employee health care premiums for next month.

If the reality is harsh for business owners and employees seeking stability, the public health rationale for the retreat to isolation is clear. Outbreaks continue to spiral at San Quentin State Prison and workplaces such as meat processing plants. Coronavirus testing backlogs have led to rationing. In some regions, hospitals are approaching capacity.

As the health crisis unfolds, changing state and local health orders have combined with looming deadlines like the July 31 expiration of enhanced unemployment benefits to create false starts, intense financial anxiety and confusion about who is supposed to be enforcing regulations on the ground. Workers and businesses alike are left to wonder how deep the recession will go, how long it will last and how many livelihoods might be gone for good.

“The best word to describe it is chaotic,” said Kaya Herron, director of community engagement and advocacy at the Fresno Metro Black Chamber of Commerce. “There’s people that are grasping at straws, that are saying, ‘I’m down to my last dime, and I don’t know when I’m going to be able to allow customers back into my space.’”

The re-closures began before the Fourth of July holiday, when Gov. Gavin Newsom ordered bars closed in Los Angeles and a half-dozen other counties on a state “watch list” for elevated virus transmission levels. This week, he ordered a halt to all indoor dining and entertainment statewide, plus a ban in 29 watch list counties on fitness centers, places of worship, protests, hair salons, indoor malls and some offices.

It may be a final blow to business leaders who have latched onto hopes of a “V-shaped” economic recovery, or a quick bounce back from economic paralysis, said Jerry Nickelsburg, director of UCLA’s Anderson Forecast. In late June, the Anderson Forecast warned that fallout from the virus had already tipped California and the rest of the country into a “depression-like crisis” with a longer “Nike-swoosh-shaped recovery” likely to last through early 2023 — that is, if businesses could safely reopen this year.

“There was a sense that the public health crisis was moving in a direction that would allow the continuing opening up of the economy,” Nickelsburg said. “Though that has not been entirely dashed, there is certainly more uncertainty.”

‘A critical time’

Hopes of a quick recovery have also dimmed in recent weeks as hiring has stalled. On the career site Glassdoor, 35% of employers have reduced job postings since June 22. Economists say it’s unclear how many are being cautious because of uncertainty and how many may be in the throes of more severe hiring freezes or nearing bankruptcy.

“The next several weeks will be a critical time for the economic recovery,” Glassdoor senior economist Daniel Zhao wrote in the job report published Tuesday. “The question is whether the worsening public health crisis will completely drown out the fledgling recovery.”

In California, one area of concern is that the unemployment rate already lagged other states in rebounding as businesses reopened this summer, said Sarah Bohn, vice president of research at the Public Policy Institute of California. After an initial blow to hospitality, tourism and other in-person professions, she’s tracked a more recent surge in public sector and health care unemployment.

“How temporary are these temporary layoffs?” Bohn said. “Is it really going to bounce back? By how much? How fast?”

“The question is whether the worsening public health crisis will completely drown out the fledgling recovery.”

daniel zhao, senior economist at glassdoor

Time is of the essence because federal legislators have not reached a deal to extend an additional $600 per week for unemployment benefits set to end July 31 amid widespread complaints in California about backlogs and unreceived benefits. Longer term, Bohn expects that the state will have to grapple with the prospect of “this crisis worsening inequality.” State lawmakers already have enacted a bitterly contested new law extending benefits for freelancers and gig workers; voters will be asked whether to curb its provisions for ride-hailing drivers with Proposition 22 in November. Other debates concern how far to expand the safety net for struggling workers in other fields.

“A roller coaster of opening and closures seems like what we should be expecting,” Bohn said. “Unfortunately it’s hard to know how many cycles of the roller coaster we’ll be on.”

Other short-term relief such as federal Paycheck Protection Program loans have so far largely failed to materialize for small businesses in Fresno, Herron said, especially those with Black, Latino or Asian owners. Her team is wading through dozens of applications for $3,000 emergency grants and running extra financial literacy programs about managing debt. She worries that the coming weeks will make or break not only individual lives, but also the entire city’s fledgling revival.

“Our downtown and our business districts are at risk of losing their tenants, but also of losing their diversity and vibrancy,” Herron said. “If businesses don’t make it through this wave, a lot of them will never reopen.”