Schools are facing a complicated array of health considerations as they decide whether and how to reopen this fall.

On one end, groups of pediatricians have recently urged districts to open schools to meet the important needs of children, as it relates to their socialization, nutrition, physical activity and mental health.

At the other end are parents who fear their children — particularly those who are medically vulnerable — will become ill or contract the coronavirus and sicken other family members.

Because so much is unknown about the coronavirus and a new syndrome, called Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children, schools need to take extra precautions to ensure students, teachers and staff remain healthy, according to an article signed by 17 pediatricians and researchers published last month in the Journal of Pediatrics.

“It’s a very challenging situation. We’ve never been through a virus like this before, and we don’t know how it’s going to act,” said Dr. Dan Cooper, a pediatrics professor and researcher at UC Irvine and one of the lead authors of the article. “There are issues schools need to address before they can plan for what school will look like on Day One.”

The authors raise several considerations schools need to address as they plan to reopen, and suggest they consult with public health experts to solve some of the challenges:

- How realistic is social distancing?

- What if students are asymptomatic carriers of the virus and bring it home to their families?

- How will teachers and school staff be affected, especially those who are older or have underlying health conditions?

- If schools decide to monitor students’ contacts as a way to trace the virus spread, how will families react to the perceived violation of privacy?

- What are the equity implications, considering some students live in small quarters with many people — conditions where the virus could spread easily?

- What will happen to students who are medically fragile? Will districts allow parents to keep those children and their siblings at home?

The Southern California chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics also issued a statement last week, saying many students — particularly those who rely on school for meals and other services — would suffer more from continued school closures than from the risk of contracting the coronavirus.

“Children rely on schools for multiple needs, including but not limited to education, nutrition, physical activity, socialization and mental health,” according to the organization. “Prolonging a meaningful return to in-person education would result in hundreds of thousands of children in Los Angeles County being at risk for worsening academic, developmental and health outcomes.”

The organization urged a balanced approach to re-opening schools, allowing schools flexibility to create different protocols for students of varying ages and needs.

Throughout the state, districts are navigating these and other issues with guidance from county health departments, the California Department of Education, teachers’ unions, the Centers for Disease Control and other groups. But conditions are changing daily and so far, few districts have devised concrete plans.

“The challenges of schools reopening are many and myriad,” said Dr. Nathan Kuppermann, a pediatrician and chair of the Department of Emergency Medicine at UC Davis who signed the article. “The idea of returning to school is a major challenge but so far it hasn’t been investigated well.”

The good news, researchers said, is that Covid-19, the illness caused by coronavirus, is rare among children. Fewer than 2% of Covid-19 cases in the U.S. have been among people under age 18, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

But, as with adults, children with underlying health conditions such as obesity or a compromised immune system are more susceptible to getting sick. And some children are contracting MIS-C, a rare but serious illness related to Covid-19.

Similar to Kawasaki disease, MIS-C causes a rash, fever and organ inflammation that can result in patients spending days in intensive care or on a ventilator. Symptoms begin appearing six to eight weeks after infection by the coronavirus, although in many cases the children had few, if any, symptoms of Covid-19.

And unlike Covid-19, most of the children who’ve contracted MIS-C so far have not had underlying health conditions.

MIS-C was first noticed by physicians in Britain and Italy in April, and since then it has been spreading. Hundreds of children in the U.S. have contracted the illness and some have died (exact numbers are unavailable because some cases and deaths may have been classified as related to Covid-19). In May, the Centers for Disease Control began tracking the illness and posted recommendations for parents and an advisory for clinicians.

“It’s still evolving. It’s hard to say what will happen,” said Dr. Behnoosh Afghani, a pediatrician and associate professor at UC Irvine who specializes in infectious disease. “We’re still studying it. As lockdowns end, there’s a potential the rate will increase. We should know more in a few weeks.”

Some parents of medically vulnerable children aren’t waiting for more research about MIS-C or Covid-19. They’ve already decided to keep their children — even the healthy ones — home from school this fall. Too much is unknown and too much is at stake, they said.

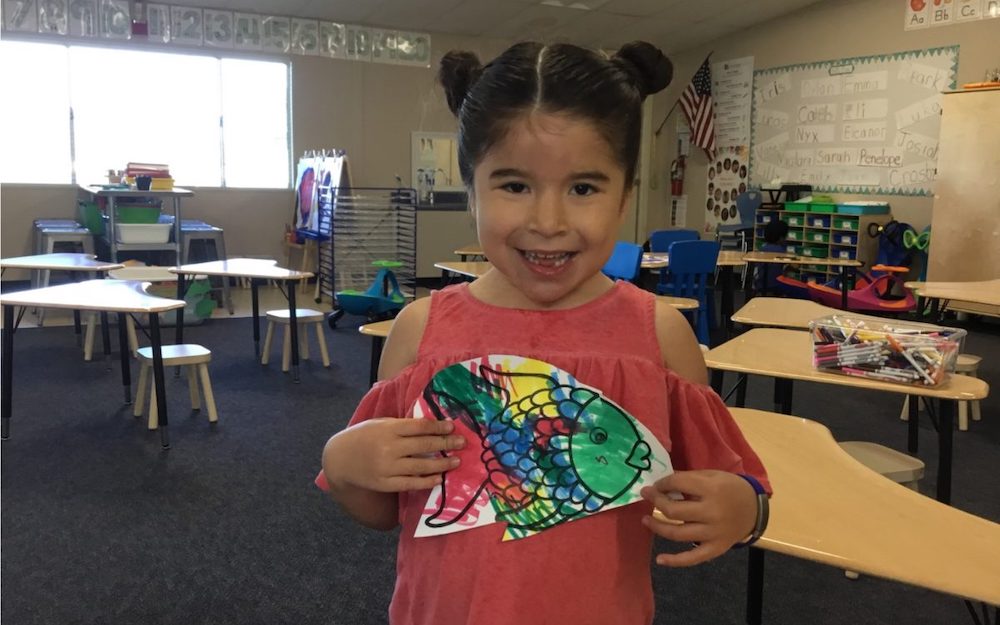

One of those parents is Aimee Ramos-Martinez, who’s opted to keep her 6-year-old daughter Alivia, who has a rare genetic disorder, and Alivia’s older sister home from their elementary school near Monterey if it reopens this fall. No matter how vigilant the school is about social distancing and disinfecting classrooms, the risk is too high, she said.

Born with Pitt-Hopkins syndrome, Alivia has intellectual and developmental delays, as well as a compromised immune system that leaves her highly susceptible to illness. Last year, she was in the hospital three times for breathing problems, and would have been there more if she wasn’t at risk of picking up more infections in the hospital environment, her mother said.

“I worry about her constantly,” Ramos-Martinez said. “A common cold for Alivia turns into pneumonia. … Personally, I can’t even think of sending a medically fragile kid like her back to school. Until there’s a vaccine, I don’t know how safe they can make it, realistically. And a vaccine is only the starting point.”

The decision was hard on Alivia and her sister, both of whom love school and miss their friends and teachers. Alivia’s older sister, who is 7, was especially upset.

“At first they had a hard time, but they’ve gotten better,” she said. “My older daughter is sad, but she understands the severity of the situation. She understands that she could be healthy but bring something home to Alivia.”

County health departments contacted by EdSource and the California Department of Public Health said the risk of MIS-C is among the many factors they’re considering in deciding whether to re-open schools this fall.

About 800,000 children in California public schools are classified as disabled, which includes those with cerebral palsy, Down syndrome and other disorders that may affect a child’s immune system.

But even some parents of healthy children are hesitant about sending their children back to school. Kathleen Cervone, an elementary teacher near Santa Rosa who has two sons in local public schools, said she knows first-hand the difficulty schools will have sanitizing classrooms, especially amid budget cuts.

“I know how hard custodians work already. But with funding cuts, it’s sort of the elephant in the room — if they cut custodial services, how are these classrooms going to magically get cleaned?” she said. “The bathrooms alone are a huge concern.”

Still, her sons miss school and miss their friends, so Cervone feels OK about sending them back if they agree to social distance on campus.

“I can teach them to be careful,” she said. “But I hope the schools can meet people halfway and provide realistic guidelines.”

The National Down Syndrome Society, among other groups, has issued advice and resources for parents who are weighing whether to send children to school.

“My biggest fear is that schools aren’t going to take the needs of disabled students into account when they decide whether to reopen,” said Kandi Pickard, the group’s chief executive. “Disabled students are so often overlooked.”

Especially concerning is that some parents might not have the resources to continue home-schooling their children in the fall, or the time to advocate for their children’s safety at school, she said.

“It’s a real equity issue,” she said.

Pickard and her husband have decided to keep their 8-year-old son, Mason, who has Down syndrome, as well as his three siblings, home from school in the fall. Even though distance learning has been a struggle, Pickard feels they have no choice.

“We can’t tell Mason, ‘You can’t hug this person,’ or ‘You can’t go down the slide with your friend.’ He wouldn’t understand,” she said. “We’ve had some really tough conversations with the whole family about what could happen, how one of them could accidentally infect their brother. It’s just too soon. We don’t know enough yet.”