While educators across the state are struggling over how and when to bring students safely back to school in the fall, teachers in at least one California classroom have already figured it out.

San Jose Middle School

At San Jose Middle School, located in Novato in Marin County, Cindy Evans’ class for special education students has been in session for ten days. Educators interviewed by EdSource say they know of no other similar effort in the state.

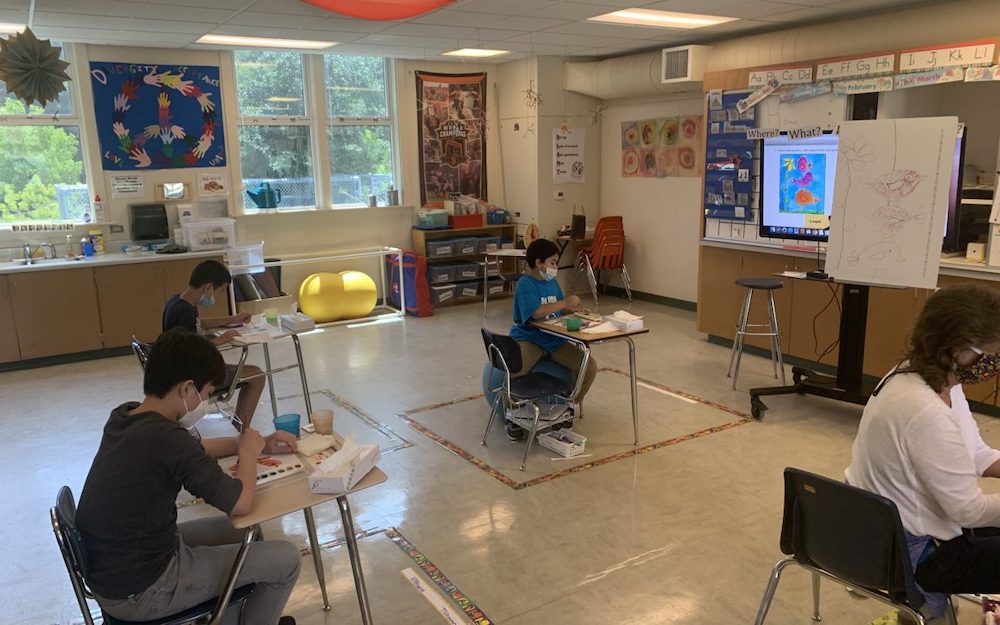

The students in the classroom, which is overseen by the Marin County Office of Education rather than a single district, come from throughout the county. As of now, five students are in school for a regular full day of instruction from 8:30 a.m. to 2:30 p.m., while three of their classmates join in via distance learning.

It is a hardly a typical class. There are four adults in the classroom: a teacher and three teacher assistants, known as paraprofessionals, who are assigned to work full-time with a student — as they were doing before the pandemic struck.

The classroom provides clues to how special ed classes might work this fall for students with the most severe disabilities. If the experience of this classroom is any guide, it suggests that social distancing is possible — but not without a great deal of effort and adult oversight.

The classroom experiment, done in close consultation with local health authorities, was triggered by the difficulties that many special ed students have had in adapting to distance learning during the pandemic. A survey of parents of special ed students in the county showed that over 90 percent were ready for their children to come back to school.

“The bottom line is the knowledge that what we have been providing hasn’t been working,” said Mary Jane Burke, Marin County’s superintendent of schools. “These are the kids that the system has not been able to engage.”

Cindy Evans said her students’ disabilities vary greatly, she said. Two are autistic, another has Down Syndrome. “I have everybody in my classroom.” Now in her 15th year as a teacher, she has not lost her enthusiasm for the profession despite taking on one of the most challenging classroom assignments.”I feel so blessed,” she said. “I love my students.”

When students arrive each morning, they go to a table outside the school entrance where their temperature is taken by a heat sensing thermometer. Parents are also asked a handful of questions — about whether anyone in their families has had a cough, fever or been diagnosed with the coronavirus in the previous two weeks, or experienced vomiting, diarrhea or other similar ailments in the last 24 hours.

Backpacks are wiped with disinfectants at the beginning of the day. Evans said they are “constantly” using hand sanitizer amd wipes, and students’ temperatures are taken again during the day.

In the classroom students desks have been placed at least six feet apart. All but one of the students wear masks. But with so many adults in the classroom, students’ movements can be monitored and they can be mostly kept apart from other students.

“It’s been running so much more smoothly than I thought it would,” Evans said.

For Laurie Carvajal, being able to bring her daughter Caroline back to school could not have come soon enough. Carvajal has three other children who are in seventh, ninth and 10th grade. Eleven year old Caroline, who is nonverbal, has a chromosomal abnormality that has resulted in significant developmental delays. For her, distance learning was a disaster. At the best of times, her mother says, Caroline showed no interest in television, or material delivered online or via Zoom. That hasn’t changed during the pandemic.

“She went two months with only having me as a teacher, and I felt I was failing,” she said. “I tried everything to make it work, I was tearing my hair out, it was so stressful. I was worried that she would go for six months without any true learning opportunities.”

That’s why the program at San Jose Middle School has been so transformative. “It is such a relief that she is getting her education in,” she said. “It was terrible when the entire burden was on me to do it.”

What makes going back to school possible is that Caroline has the support of a fulltime assistant in the classroom who monitors her throughout the school day, as she has during the school year.

Caroline is probably at higher risk of contracting the coronavirus, Carvajal acknowledges. “She likes to touch things, and she likes to touch her mouth, so she is a prime target (for the virus),” she said. In addition, it is impossible for her to wear a mask because she simply removes it.

The school also doesn’t serve meals (she brings her own lunch), and instead of a regular recess, students just walk around the school. ”So being in close proximity to other kids is not really a problem,” Carvajal said. “My comfort level comes from knowing that they are taking precautions, and that she has someone standing next to her all the time, making sure she is not exposed to anything and the kids are kept far apart enough.”

Marc McCauley said his 13-year-old son Willie, who has been diagnosed with what is referred to as an “autism spectrum disorder,” actually did fine with remote instruction but returning to his school was so much better.

He says he worried unnecessarily that changes in the school environment his son had gotten used to, like going to school by bus and eating in the cafeteria, might be a problem. “He really seems to enjoy being back,” he said.

“Yeah, I enjoy being back in Cindy’s class,” Willie interjected in the background while his father was being interviewed for this article.

Marin Community School

The county has another pilot program underway about 15 minutes away at the Marin Community School in San Rafael. It serves just over 50 middle and high school students who have a range of behavioral problems that have made attending regular schools difficult, if not impossible. Since last week, each day a different group of about 10 students comes to the school for four hours of in-person classes. It too has a very high student to adult ratio, with a teacher and a full time “learning coach” overseeing each class.

Co-principal Katy Foster says the effort to get students back to class for even just a day was based on the school’s guiding philosophy that teachers’ relationships with students are the key to their success.

The Marin County experience suggests that it is possible to provide in-person instruction to some of the most challenging students in special education classes. Whether it is generalizable to the general population is another question. Carvajal doubts that it is. “We drop students off in a small parking lot, with parents providing transportation,” she said. “I stand with her until it is her turn to check in.” And she notes that just a few students are taught in a classroom the same size as her son’s seventh grade class, which has 27 students.

County superintendent Burke said that the experience underscores the fact that serving many special education students “will require a great deal of individualization and different models.”

“These are kids that the system has not been able to engage,” she said. “We hold the belief that the miracle-making process of school is interaction with kids. That is where you see the magic.”