A group of researchers at University of California at Berkeley and UC San Francisco on Monday announced a joint study of more than 120 available antibody test kits to examine potential immunity, temporary or otherwise, to the COVID-19 coronavirus.

The researchers have already found that some tested for coronavirus antibodies have developed antibodies, particularly around two weeks after the initial infection. However, several of the test kits the research team has examined have significant false positive rates, meaning those testing positive for antibodies may have never contracted the virus in the first place.

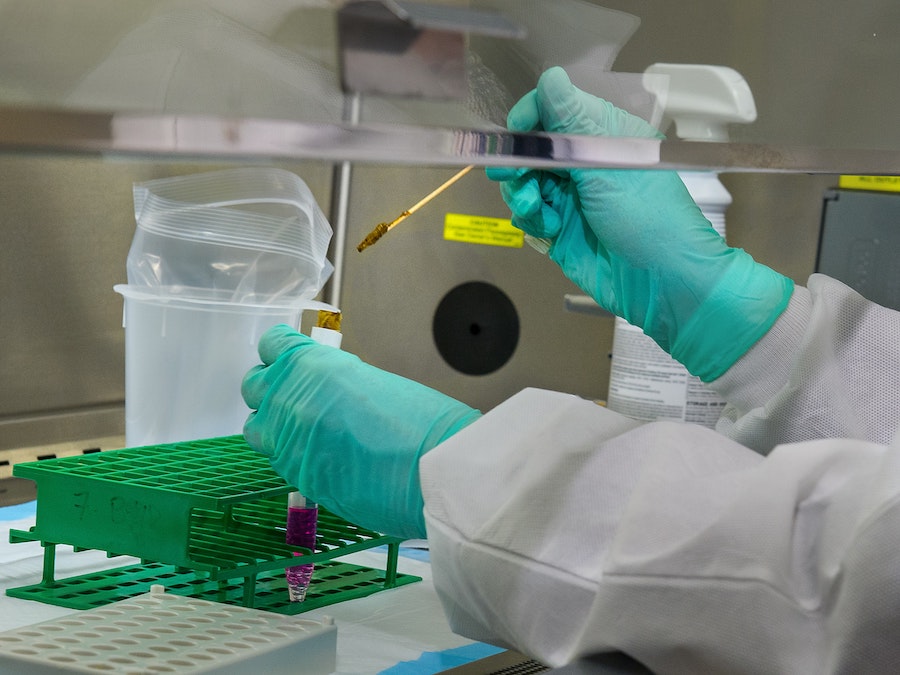

While nasopharyngeal tests for the virus can determine whether a patient is currently infected, blood tests for antibodies can compliment the standard swab test and determine whether a patient is in the early or late stages of the infection.

The researchers cautioned, however, that the antibody tests are not yet able to determine the chances of future infection and how long immunity to the virus lasts.

“These tests are widely available, and many people are buying and deploying them, but I realized that they had not been systematically validated, and we needed to figure out which ones would really work,” said Patrick Hsu, an assistant bioengineering professor at UC Berkeley and an investigator at the school’s Innovative Genomics Institute. “This is a huge, unmet need for public health.”

The research team has, to date, studied 10 point-of-care tests similar to home pregnancy or HIV tests and a pair of laboratory detection tests. Many of the samples the researchers have targeted have not yet received emergency use authorization from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

The dozen antibody tests were analyzed next to about 300 blood samples, many of which were from coronavirus patients at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital or the UCSF Medical Center. About one-third of the tests were taken before July 2018 and theoretically should not include any coronavirus patients.

But the team is not limited just by the number of tests at their disposal, according to UCSF associate professor of microbiology and immunology Alex Marson.

“One of the cornerstones of lab medicine is that a new test is compared to a definitive reference or gold standard,” Marson said. “We do not have a gold standard yet for COVID-19 serology testing, so we are amassing data on a standardized set of blood samples and really looking at how each of these tests performs in relationship to all the others.”

The researchers posted the first results of the study at covidtestingproject.org prior to peer review and submission to a medical journal. As such, the researchers cautioned that while the preliminary results can help inform state and federal officials seeking to buy antibody tests, they should not be taken as established, medically accurate data.

“This is a huge, huge community effort,” Hsu said. “A lot of people really came together. One of the things I think is cool about this study is how many people repurposed themselves from what we normally do to respond to this pandemic.”