Our country has just lived through the highest stakes trial our democracy can muster — the trial of an impeached president.

Although many lessons could be found in the gory political smack-down, one of the most essential is the importance of a fair, unbiased jury.

Most people hate jury duty (including most senators, apparently). As a veteran criminal defense lawyer and professor of public policy, I am often asked what people can say to get out of it. Here is my advice: do what you can to get in it.

Jury service is a front-row seat for real-life “Law and Order,” a chance to impact someone’s life, and a rare opportunity to get involved in our democracy.

Most people — especially in the East Bay — avoid jury service. Alameda County has some of the lowest participation rates in the state. Last year, Alameda County Superior Court executive officer Chad Finke told the East Bay Times that, on a good day, the Wiley W. Manuel Courthouse gets a response rate of 20% to 30%. On a bad day? Eight percent.

The California average, in contrast, is a 46% jury yield. Even at the highest rates, it’s astonishing how many people miss out on this bucket-list experience. Especially in this age of attack on public institutions, disregard for constitutional principles, and a growing sense of injustice (and even tyranny), there is no better time to be a juror.

Diverse jury pools and juries reinforce the legitimacy of the judicial system. They also support the constitutional right to a fair trial and the right to be represented by a “jury of your peers.”

Yet the racial makeup of those who serve on Alameda County juries is worrisome. According to research from a decade ago, unfortunately the most recent available, there is substantial underrepresentation of African Americans in Alameda County jury pools. They represented 18% of eligible jurors, but only comprised 8% of the people who appeared for jury duty. The same was true to a lesser extent for Latinos.

The impact of the jury pool on conviction rates is straightforward and striking: The presence of even one or two African Americans in the jury pool results in significantly higher conviction rates for white defendants and lower conviction rates for black defendants.

Diverse juries directly reduce bias in the criminal justice system. They also create feelings of empowerment for groups that have been historically excluded from civic institutions. Ultimately, diversity in juries shows that constitutional principles matter and that democratic institutions are legitimate.

Unlike dropping your ballot in a mailbox, with jury service, you experience real-life drama. This is not televised, scripted “reality;” it’s real. You decide whether the woman accused of a robbery was at her friend’s house the night of the crime, you decide whether the young man intended to cause sustained fear in his co-worker when he texted those threatening words.

One friend told me her experience as a juror in a death penalty case was so intense that all the jurors kept in touch for years afterwards. Nothing compares to first-hand experience of the justice system. Not even binge watching “Making a Murderer.”

Of course, none of us have the luxury of taking days out of our lives to sit in that plastic chair, waiting around and getting paid $2.14 per hour. But, rather than focusing on the negatives of jury service, remember that justice isn’t a principle etched in stone above a courthouse door, justice is what can happen in thousands of cramped, nondescript rooms across the country when 12 people get together to decide someone’s fate.

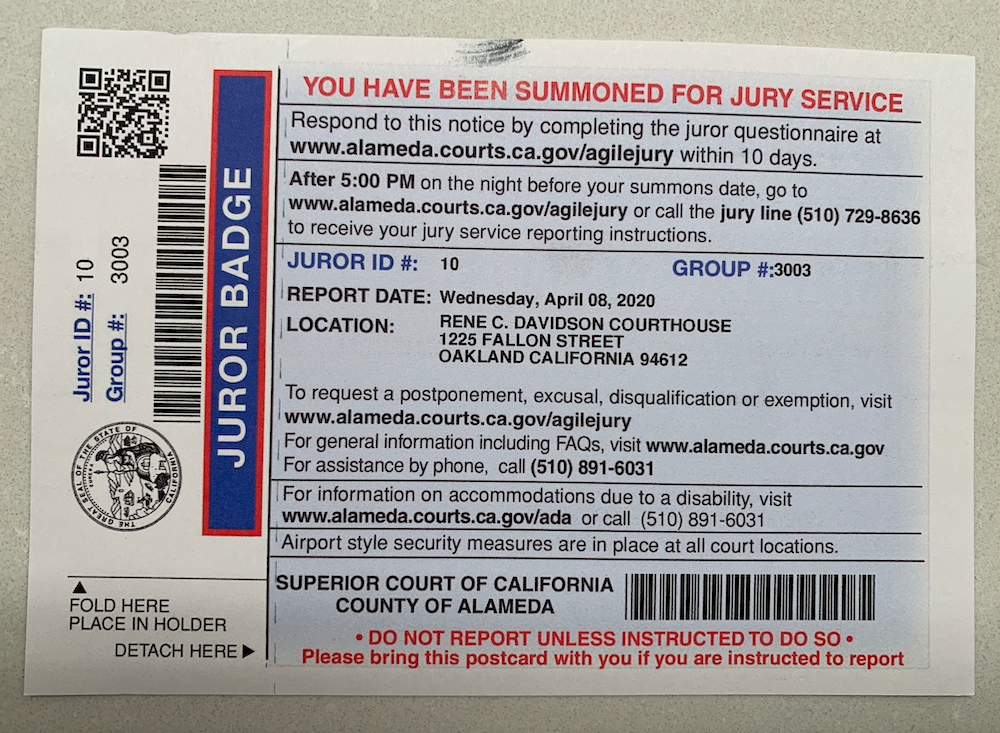

With all of this in mind — the unique aspects of the experience, the positive impact you can have, and the desperate need of our democracy for your fair and unbiased participation — consider that summons not as a burden, but as an invitation to change our community and our country.

This commentary first appeared in the East Bay Times and is reprinted with permission of the author.