With maybe a week to go before a “wave” of novel coronavirus infections slams California, health care professionals are warning that steps need to be taken to protect immigrant populations and communities of color, which face a greater risk of being exposed.

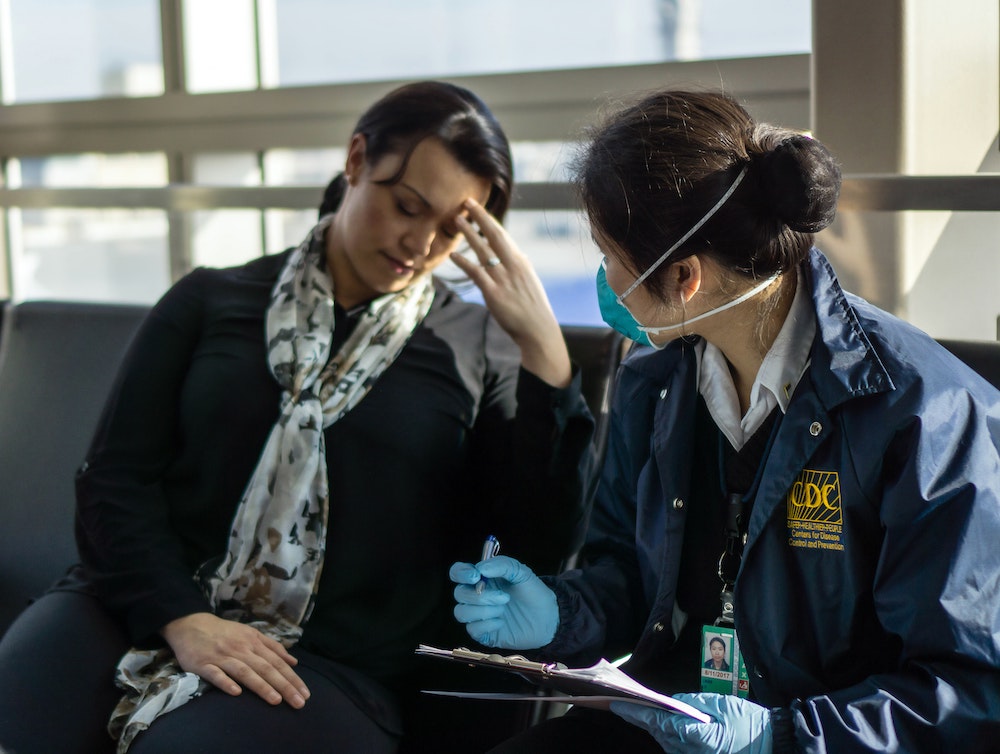

As the virus continues to spread at exponential rates and millions of Americans shelter in place, health care systems around the country are pleading for additional resources in order to contain COVID-19 and treat patients stricken with the disease. These resources are particularly critical for communities of color and immigrant populations, where low incomes, employment patterns, immigration concerns and lack of adequate health insurance coverage could combine to have devastating impacts on the state’s ability to fight the virus.

“The wave is about a week or two away before it comes to California,” said Dr. Daniel Turner-Lloveras, a professor and researcher at Harbor-David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles.

One of the reasons that immigrants and people of color are at higher risk is that they tend to have limited access to health care, since large parts of these populations are either uninsured or underinsured. For example, 43 percent of undocumented immigrants don’t have health insurance at all, said Turner-Lloveras, who discussed the pandemic Friday as part of a panel of health care professionals and civil rights leaders during a video conference call sponsored by Ethnic Media Services.

Turner-Lloveras said state and federal officials need to ensure that everyone, regardless of immigration status or insurance coverage, is getting the information and resources they need to stay safe. “One cannot contain a virus outbreak by providing care to only some of the population,” Turner-Lloveras said. “And we can’t successfully contain a virus outbreak if there are some among us who are afraid to seek care.”

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents should stop detaining people who seek health care, eliminate overcrowding at detainment centers and end the practice of forcing people awaiting asylum to remain in Mexico while their cases are pending, he said.

Communities of color and immigrants face an increased risk of not only being exposed to and contracting the virus, but they also face a higher risk of being stricken by the health and economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, according to Dr. Rishi Manchandra, CEO of HealthBegins, a health care consultancy.

While millions of Americans are being asked to stay home and avoid contact with people outside of their households, many immigrants and people of color who hold down low-wage jobs with little or no sick-leave — and for which telecommuting is not an option — are being forced to make the choice between going to work or sheltering in place. “They also face an increased risk of exposure because of the type of work that communities of color and immigrant communities are engaged in,” Manchandra said.

For example, many work as grocery store cashiers and delivery drivers and in various parts of the nation’s health care industry — all of which require close contact with customers and patients. Also, these populations tend to live in dense urban areas, many in tightly packed public housing facilities with larger families all living under one roof, and also tend to experience homelessness at higher rates, Machandra said.

Additionally, language barriers are preventing many people from receiving and understanding vital public health messages, he said. Communities of color and immigrant communities also face greater risks of having to deal with more severe complications if they do get sick, since they tend to suffer from higher rates of chronic illnesses.

For example, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander groups have twice the risk of diabetes than the population overall, Machandra said “We know that the ability to absorb the costs of both the health impacts and economic impacts is limited among people of color,” he said, noting that the median white family has 41 times more wealth than the median black family and 22 percent more than the median Latino family.

Asian American and Asian immigrant groups also now face increased rates of COVID-19-related hate crimes, according to Manju Kulkarni, executive director of the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council.

Kulkarni’s group recently helped build a website dedicated to recording incidents of hate crimes related to the pandemic. “We have received almost 700 reports of incidents of hate across the nation in seven days,” Kulkarni said. “This is something that individuals and families are experiencing across the country.” Most of the cases involve verbal harassment at grocery stores, big box retail chains, on the street and on public transit, Kulkarni said. “All of these things are preventing Asian American families from getting groceries, from getting prescriptions and even going on a short walk around their neighborhoods because they are worried for their safety,” she said.

The Stop AAPI Hate webpage can be found here: http://www.asianpacificpolicyandplanningcouncil.org/stop-aapi-hate/