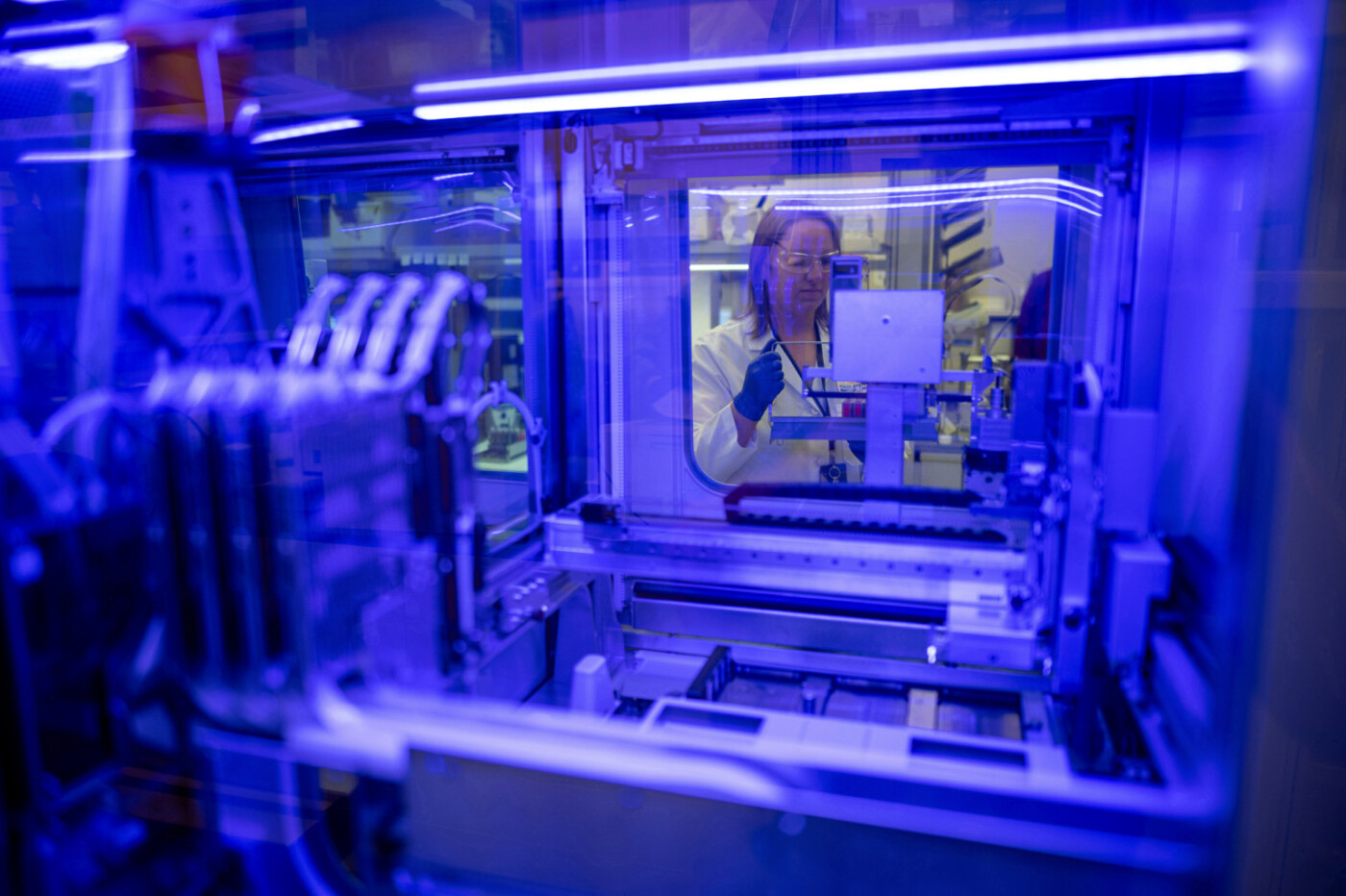

As California officials desperately try to slow the spread of the novel coronavirus, Chris Miller is coaxing a sample of the virus to grow in a secure laboratory at UC Davis.

Working in a laboratory nestled inside containment rooms and cut off from the world by filters, scientists dressed in space suit-like protective gear are feeding cells to a virus isolated from a COVID-19 patient at UC Davis Medical Center.

The goal is to create a supply of viral genetic material to help the clinical pathology team develop new tests. Without these viral samples to provide an unequivocally positive result, researchers can’t tell if a test is truly working.

It’s a new mission for Miller, who, until about two weeks ago, was studying HIV and working to develop a pandemic flu vaccine. “Flu, at the time, seemed like the virus that was going to kill us all and was going to be the big pandemic,” Miller said. “But it seems like coronavirus has other plans.”

Miller’s flu research meant he had the right facilities to join the fight against the novel coronavirus when Nam Tran, professor and senior director of clinical pathology at UC Davis, recruited him.

“When I got the call, my reaction was, ‘Drop everything,’” Miller said. “I’ve never been asked to directly contribute to an emerging health emergency that had to be addressed in days and weeks. And so I was just grateful that I had the expertise to be able to help the hospital.”

With California Gov. Gavin Newsom’s order for Californians to shelter in place, university campuses across the state began gauging the risk of letting research continue. And scientists are finding their work, plans and lives upended by the spread of the novel coronavirus.

Some, like Miller, are switching gears to fight the virus — but for others, research is grinding to a halt, including critical medical research. Still more are caught in limbo, waiting to find out if they can continue important studies without endangering themselves, or others.

William Ota, a second-year graduate student at UC Riverside, has put his research on ice — and hopes it stays frozen.

Ota studies a fish native to southern California called the Santa Ana sucker, including what eats it. That’s why he has 1,500 stomachs from invasive species of fish divided between a freezer in his lab, and a freezer at the Riverside Corona Resource Conservation District.

He’d planned to start dissecting the stomachs and looking for traces of the Santa Ana sucker in the contents last week. Now that the UC Riverside campus has shut down to all non-essential personnel, Ota will have to wait. At first, he worried that if power to the freezers went out, he wouldn’t be able to catch it. “Which is scary,” he said.

Now, he’s found out that the university will allow people on-site to check on equipment and do maintenance, he said — but he’s not allowed to start cutting into those fish stomachs. So even if the freezers stay on, and those stomachs survive unscathed, Ota worries that the delay will cost him time and money if his work stretches beyond the five years he has funding guaranteed.

“There’s no guarantee that if you fall beyond that five year period that you’re actually going to get any teaching money, any grants or support from the university,” Ota said. “That’s something that I know myself and other students in my program whom I’ve talked to are worried about.”

Lynn Sweet, a plant ecologist and research specialist at UC Riverside, also is grappling with shutting down some research as she waits to hear what the agencies funding it still expect from her. “We don’t know how our funders will respond to this crisis. We don’t know the degree to which we’ll be given any leeway due to this. We have agreements we write, and deliverables that are due,” she said.

Sweet already has pressed pause on one study aimed at protecting stands of Joshua Trees from wildfires because it would have been conducted by volunteers through environmental non-profit EarthWatch. She was especially concerned about volunteers over age 65 who would be traveling to the park and living in close quarters. “As much as we want to get the research done, it’s not worth risking folks’ lives,” Sweet said.

Another project out in the Mojave desert is continuing, for now. From her home office hastily constructed in a closet, Sweet is supervising a four-person crew as they keep their distance from one another and survey desert tortoise habitat in a stretch of the Mojave owned by the Department of Defense.

The desert tortoise is a federally threatened species, and the goal is to find out how well its home and food sources are holding up to environmental disruption like climate change and off-road driving. The study is time-sensitive — scheduled to match data collected 20 years ago. “We don’t get good years to study plants all the time,” Sweet said. “If we miss this year, next year could be a drought … That’s why it’s really important.”

It’s not just environmental research that’s on hold; biomedical research that can’t be readily focused on the novel coronavirus is facing roadblocks, too.

Clarissa Araújo Borges, a postdoctoral scientist at UC Berkeley’s School of Public Health, is investigating new antibiotics to treat drug-resistant infections of the urinary tract and bloodstream. “Antibiotic resistance is one of the greatest global public health challenges of our time. New drugs are urgently needed,” Araújo Borges said.

It’s important research for people who find themselves in the hospitals, fighting not only what landed them there, but what they picked up in the hospital itself.

Araújo Borges spins out a hypothetical scenario: “You’re hospitalized, and then you’re weak, and then you get a bloodstream infection there through a catheter,” she said. “Sometimes they’re resistant to drugs available and there is nothing to do.”

She found a promising candidate and tested it in a dish. The next step was to test it in mice — but when UC Berkeley closed its labs except for essential activities, Araújo Borges had to appeal to keep her research going. “If you have research that you’ve been doing for months, and then you have to stop and lose it, it’s terrible because it’s a lot of money and time.”

Still, she said, she agreed with the university taking preventative measures, and said that others who aren’t collecting salaries during the shutdown have it worse.“People losing jobs, like waiters, Ubers, restaurants, small businesses — it’s terrible,” she said.

After waiting a week, Araújo Borges finally heard back from the university: she could go back to work.

For UC San Francisco graduate student Johnny Yu, the novel coronavirus pandemic chased him out of the lab, and out of San Francisco entirely. This academic year, UCSF set graduate student stipends at $40,000, according to the university, which Yu said is too low to afford to live in San Francisco.

That’s why he lives in a van — a tiny space with a chemical toilet where he can’t envision quarantining if he got sick or weathering an extended shelter-in-place order. “It’s suitable for sleeping at night. But for a two-month lockdown, it would be pretty impossible,” Yu said. He fled instead to a rented yurt in Grass Valley with his wife, where they’re digging into savings to pay for their stay.

Yu studies how a cancer evolves from a primary tumor to become a metastatic tumor, and looks for potential treatments. “You can treat a primary tumor, you can remove a primary tumor, but if you have a metastatic tumor, it’s pretty much the end of the game,” Yu said.

He’s had to abruptly end his experiments as he prepares to stay away from the lab for the foreseeable future. “I can’t do any of the experiments I had,” Yu said. “We killed everything. We killed all the mice, we killed all the cells.”

He estimates that stopping now will set his experiments back six months — and as other cancer research grinds to a halt, the search for new treatments could be delayed even longer. “If we can’t find the cancer drugs and cancer targets, industry can’t take it and develop it into a drug,” he said. “At least a year, I think it will set back the entire field of cancer.”

Yu’s Ph.D. mentor, assistant professor Hani Goodarzi (who is not responsible for setting Yu’s salary), said the same story is true for many of Yu’s colleagues. Half of Goodarzi’s lab studies cancer progression from the lab bench, like Yu; the other half models cancer computationally.

The experimental researchers, Goodarzi said, are at a scientific standstill right now. “We actually shut down the lab a few days before UCSF shut down,” he said. “So we’re focused on writing papers, and grants, and added a journal club discussion via Zoom — to keep everyone engaged while they can’t be at the bench.”

With no ongoing lab research and no way to pivot to studying the novel coronavirus, Goodarzi did what he could to help with the fight. He gathered up all the gloves and surgical masks his team doesn’t need now and donated them to UCSF Health.

“I wish we could do more,” Goodarzi said. “We kind of feel useless, to be honest …The way that we can contribute is really just like everyone else, just by staying home.”

Get the latest on coronavirus in California with our frequently asked questions, dashboard tracking the numbers and our latest updates.