How do you put 40 million people and the world’s fifth largest economy on virtual lockdown? Gradually and then suddenly, it turns out.

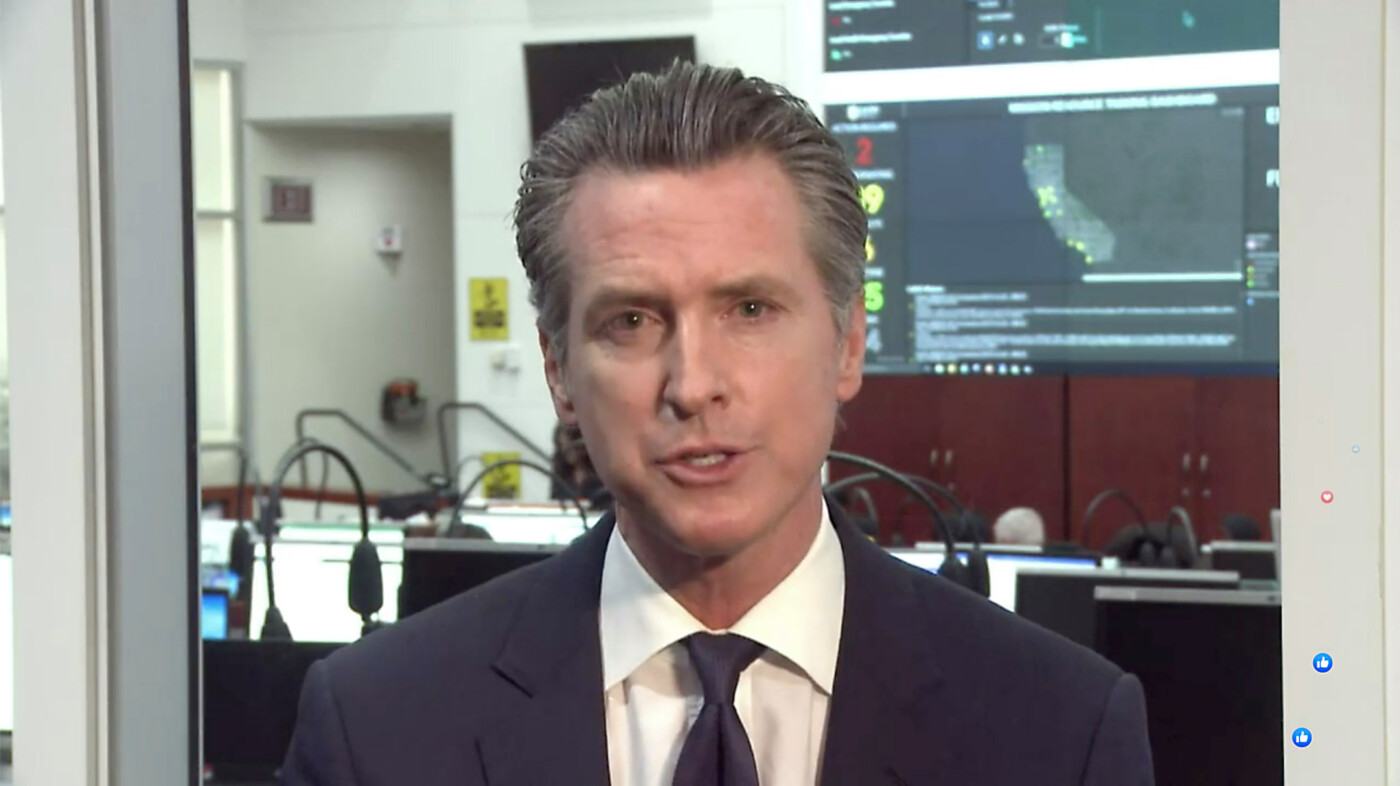

Bit by bit, first in large gatherings, then in restaurants and bars, then theme parks and schools, then city by city, Gov. Gavin Newsom managed to slow walk a thousand public school districts, a state full of restaurants, Disneyland and even L.A. and San Francisco into voluntarily shuttering and sending people indoors.

By the time Newsom issued a mandatory order to stay at home on Thursday, it was obvious that, for a week, this was where things had been inexorably heading.

“We will look back at these kinds of decisions as pivotal decisions,” Newsom said. “If we’re to be criticized at this moment, let us be criticized for taking this moment seriously. Let us be criticized for going full force and meeting the virus head-on.”

The order marked the first time during the coronavirus pandemic that Newsom used his authority to make a demand on the state that carries the force of law — a shift from his earlier strategy to restrict activity through guidance instead of mandates. For days before ordering people inside, Newsom said he took the lighter approach because he had faith people would “do the right thing.”

Other governors, meanwhile, were issuing mandatory orders to close schools and shut down large events. (Or, in some cases, going to the opposite extreme.)

“Everyone has their own style,” observed Juliette Kayyem, a former assistant secretary for homeland security under President Obama.

“The challenge for the governors is there has been almost no federal guidance… so they each have become presidents unto themselves for their own jurisdictions.”

“There’s a science part of it. And then there’s the ‘getting everyone to go along.’ Because we’re going to ask people to do really hard things.”

—state Sen. Richard Pan

House GOP leader Kevin McCarthy criticized Newsom for taking such a drastic step, telling Fox News that Newsom could stem the spread of the virus “without shutting down the entire state.”

But state Sen. Richard Pan, who is also a practicing medical doctor, praised Newsom for taking a gradual approach, saying it makes sense for managing a public health crisis that requires buy-in from millions of people to stem the spread of a pandemic.

“If the first we hear about it is it’s a demand by the government, people tend to be less responsive,” the Sacramento Democrat said Friday. “We need to bring people along and have people own that decision and understand, ‘This is why this is so important.’”

Pan noted that Newsom’s approach recognizes the difficulty of getting a populace larger than Canada’s to drastically upend their lives and potentially devastate their incomes.

“There’s a science part of it,” he said. “And then there’s the ‘getting everyone to go along.’ Because we’re going to ask people to do really hard things.”

Newsom’s decisions during the pandemic also reflect two themes emerging in the new governor’s leadership style. The first is his deference to local government. Newsom — a former mayor of San Francisco — often emphasizes that the nation’s largest state includes vastly different regions that vary in their needs, from dense cities to sprawling suburbs to remote rural communities.

Before issuing a statewide order, Newsom let cities and counties issue the strictest rules, with several requiring their residents to shelter in place days before he told the entire state to do the same. This approach echoes Newsom’s predecessor Gov. Jerry Brown, who often preached the principle of “subsidiarity” — a fancy way of saying issues should be handled by the lowest level of authority possible. (Newsom uses different lingo: “Localism is determinative,” he says.)

The other emerging theme is that Newsom appears to follow a governing style made famous by President Theodore Roosevelt, who often said his approach to foreign policy was to “speak softly and carry a big stick.” It means he liked to negotiate peacefully for as long as possible, but prepare to take harsher actions.

Newsom made clear this week that he can, literally, call in the troops if Californians don’t follow his order when he announced Tuesday that he’s put the National Guard on alert.

“We have the ability to do martial law, things like that, layer new requirements and authority,” he said days before issuing the order to stay home. “If we feel the necessity to do that, we will do that.”

But for the most part, Newsom’s strategy has been less about demands than easing Californians, fast, into an increasingly urgent vision — with an expectation that they will comply, if he can make the stakes clear before the worst happens. In many instances, it worked.

When Newsom told the public last week to stop attending events of 250 or more people, for example, he didn’t mandate that large theme parks like Disneyland shut down. He did, however, make that exemption public and mention that he had spoken with Disney’s executive chairman and former chief executive Bob Iger. Within hours of his announcement, Disney announced it would voluntarily close its park, and other theme parks followed suit.

Newsom’s incremental touch echoes the approach he used as mayor of San Francisco, when he was known for a reluctance to deploy harsh mandates.

“He always tried persuasion first before cracking down,” said Nate Ballard, who worked for Newsom as mayor and recalled him trying to rein in chaos at rowdy Halloween gatherings without calling for totally shutting them down.

During the swine flu epidemic of 2009, “we were one of the counties that did not close schools” though many did, recalled Anne Kronenberg, who was Mayor Newsom’s director of emergency management.

“Gavin took flack for that initially,” she said. “But it was the right thing to do.”