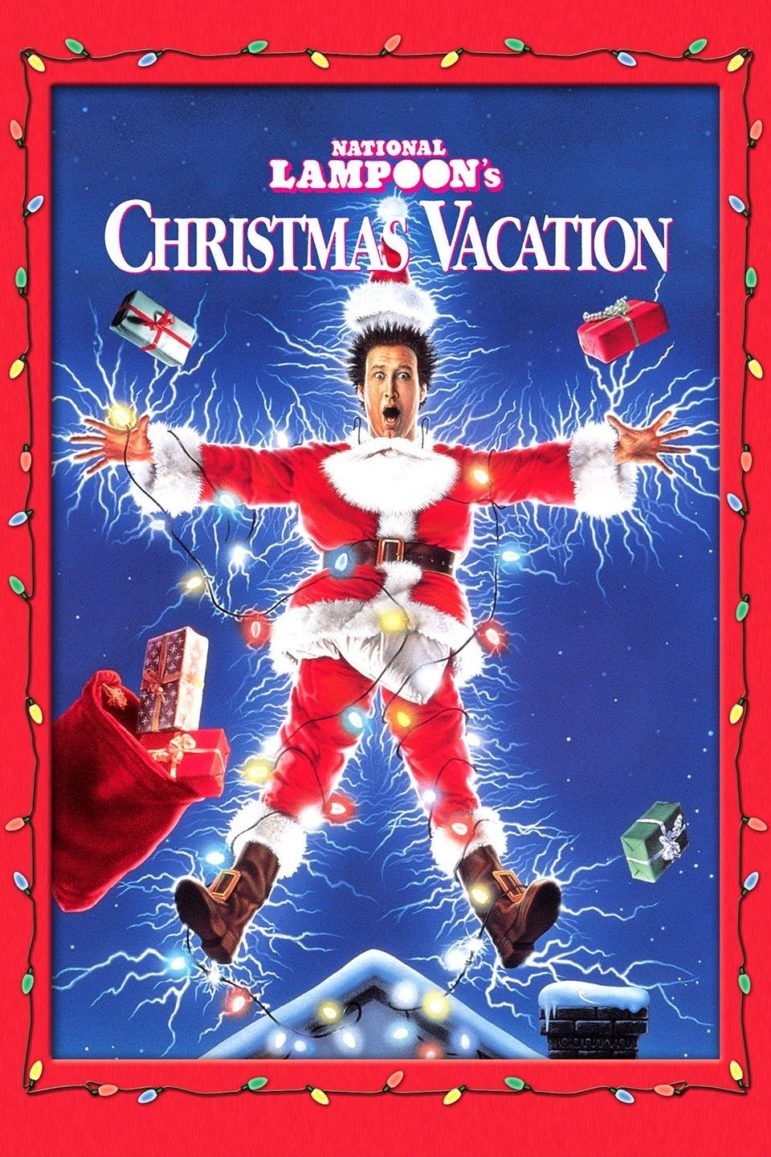

One of my favorite movies of all time is National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation. Often, I feel like I’m married to Clark Griswald, with his obsession with the outdoor twinkle lights and relentless optimism about the perfect family Christmas. One of my favorite lines from the movie is when Clark’s teenage daughter, Audrey, complains about sharing a bed with her “perverted” little brother. Her mother Ellen says to her, “I don’t know what to tell you. It’s Christmas; we’re all in misery!”

Christmas is miserable for many people. The stress of buying all those sweaters, hauling out bins of smashed decor, attending the dreaded cookie exchange with your store-bought or generally inedible baked goods. None of this compares to the psychological stress inherited from generations of dashed holiday expectations and torturous meals with dry turkey and family fights. This goes to a larger issue rattling around my egg-nogged brain lately: Even smart, thoughtful adults inherit, and then act out, their own parent’s shortcomings, problems, and neurosis. Do they get overwhelmed and scream during the holidays? We scream, too. At other times, do they pretend everything is perfect and bottle up their real feelings? We bottle up our feelings, too. Our parents, of course, inherited their holiday traditions and most of their other personality defects from their parents. And so it’s incumbent on us, especially the parents among us, to stop the madness, or to at least mitigate the misery.

In my mother’s family, Christmas was always a time when her dad got really drunk, yelled at everyone, and then threw plates of mashed potatoes at the wall. My mother and her siblings carried on these great traditions in their own ways. My mom dropped so many f-bombs while hanging the lights on the Christmas tree, she eventually gave up having a tree altogether. One year when I was in my early teens and my sister was in late toddlerhood, we begged for a Christmas tree so relentlessly that my mother screamed “FINE,” dragged in a potted pine from the back porch, and threw it in the corner of the living room. To call it a “tree” is quite generous. It was a twig, really, with a few branches, skinny and askew. It could only withstand the weight of a solitary strand of lights which greatly reduced the swear words but made it an even more pathetic reminder of how far my family had fallen from the joyous holiday moments we saw on television.

My mom’s sister is famous for announcing her first bi-polar episode in her standard Christmas letter to friends and extended family. She also threw a bowl of peas at Christmas dinner one year. I am pretty sure there was an f-bomb in that episode too.

I remember another Christmas when I got into a fight with my uncle about affirmative action. I (of course) defended it as he spewed Libertarian tirades my way. Sure, I had clogged his garbage disposal with potato peelings, causing a massive backup in the sink and dishwasher, for the second year in a row, but I was a 19-year-old sophomore at Cal. Did he really have to call me names like “crazed daughter of hippies” and “birkenstock-wearing idealist”? We fought until he made me cry. That really shut him up. In hindsight, my uncle probably struggled with his own stress of the holidays, financial or personal, inherited or circumstantial.

I have no real reason for holiday blues. Except for the worry about the inevitable liver transplant that I’ll need after too much holiday cheer, I have all the makings of a joyous season: A husband that loves twinkle lights, money to buy presents for my family, a warm home to decorate. I’ve even trained my kids to hang the tree lights while I mostly watch, direct and sing along to Mariah Carey. And still, I feel dread at times during the holidays. To be honest, I get overwhelmed by it all. And usually when it’s over I feel exhausted and dissatisfied. Which I’m sure is how my mom felt as a single mother with barely enough money for gifts and even less bandwidth for stocking stuffers and separate wrapping paper for “Santa’s” gifts. (They were just thrown under the tree, unwrapped.) My holiday dread and all of my other default modes of reacting and interacting happen automatically, as if my mother were shoved inside me, forcing me to yell and drag pathetic potted trees inside. My default modes are deep ruts created by my parents, my grandparents, and their parents … and I easily fall into them.

My attitude around Christmas is actually one of the easier ways I have broken away from familial customs. It’s not too challenging for me to buy a tree, sip the nog, and enjoy it. It’s harder to share difficult emotions without anger or to believe that what I’ve done is good enough. It’s harder for me and that’s how I know where to focus my efforts. Of course, it’s a lifelong project to correct deeply ingrained and inherited behaviors or to rewrite those negative stories in my head that were formed in my childhood. Yet the holidays provide endless opportunities for personal development. Family traditions and gatherings provide so many chances to practice patience, humor, mindfulness, and generosity.

This year, I’ll be practicing joy and family connection rather than misery. So like Clark says, “When Santa squeezes his fat [backside] down that chimney tonight, he’s gonna find the jolliest bunch of [us] this side of the nuthouse!”

We’re all in this together! Merry Christmas!