Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Suzan-Lori Parks (Topdog/Underdog) crafts a powerful, eviscerating, absurdist and timely play in White Noise, but one that leans too heavily upon a major plot contrivance and suffers from flagging energy at various points.

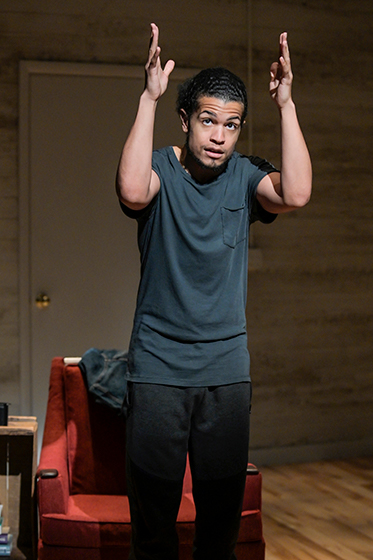

Directed by Jaki Bradley, with Adam Rigg (Scenic Design) and Mikaal Sulaiman (Sound Design), White Noise is haunting. The work’s inner groove burns like wildfire, exposing America’s great wounds and wickedness — slavery, racial profiling, blue-on-black violence, liberty and justice for some, not all. As the play’s central protagonist and catalyst Leo (Chris Herbie Holland) says, “Waking up is hard; staying “woke” is harder.” The pain of ongoing racism, alive, rampant and acknowledged within each of us, never ceases.

Leo is a 30-something-year-old painter who has suffered insomnia since age 5. His condition intensifies, especially after abandoning the “whoosh” of a white noise machine that helped him sleep but zapped his artistry. During a late-night “walk while black” in an upscale neighborhood, he is brutally beaten by police.

Leo seeks security from his three besties, who periodically meet up at a bowling alley. Girlfriend and do-gooder lawyer Dawn (Therese Barbato), offers to help him sue the police. Their college friends step up: Misha (Aimé Donna Kelly) the host of a vlog, “Ask a Black,” and Ralph (Nick Dillenburg), whose professional calling is can’t — can’t get published, get tenure, or get beyond his momentous self-pity — provides hackneyed bowling tips and chest bumps.

Photo: Alessandra Mello/Berkeley Rep

The plot turns on an improbable situation: Leo decides protection from police violence and “showing the world how far we have not come” will happen if his “bro” Ralph, now a rich white dude, having inherited a fortune from an estranged millionaire father, purchases Leo as a slave at a price of $89,000. (Covering Leo’s credit card debt and college loans.) Implausibly, convincing Ralph to participate is easy and Dawn jumps forward to notarize and Misha to sign as witness a thick contract for a 40-day slavery term. Credibility and audience empathy are lost — these characters are not friends or lovers anyone deserves.

Acquiring shades of a fever dream, Act II has Ralph relishing his role as master. He joins a “white club” of like-minded racists — an obvious mirror of the Ku Klux Klan — and places a punishment collar around Leo’s neck while having him hold a “genetically modified bonsai cotton plant.” Later, he tells the audience in elated tones during a monologue about ordering Leo to strip, so club members can bid on Leo’s physical prowess, among other atrocities.

But the choke collar: It is the visual moment that tugs most egregiously, yanking this viewer right out of the drama to think, “Wouldn’t Leo call off the deal? Wouldn’t Ralph? What did the real life African American actor think, say, or first do when asked to don the historically accurate device?” And most disruptive: “Why don’t we, the audience, stop this now? How far is too far, how much pain relived is too much pain, even in the name of “wokeness” and art?” Maybe not stopping the pain is the very reason White Noise should be seen and celebrated.