California urges other states to go its way: Let citizens, not politicians, draw district maps. But the state’s having a bit of trouble attracting a diverse, qualified pool of citizens willing to do the job.

Ask Cynthia Dai what she’s been up to in her spare time, and she’ll say “saving democracy.”

Nearly a decade ago, she discovered that applications were about to close for citizens willing to serve on a new California commission that would redraw new congressional and legislative districts. The stakes were enormous. The state’s politicians previously drew lines to protect their jobs and maximize their party’s seats — one late Democrat called the resulting maps “my contribution to modern art.” But by 2010, the state was creating a citizen’s commission to do the job more fairly.

Dai held degrees in electrical engineering, computer science and an MBA from Stanford. She decided to go for it. Why, when it required her to conquer an application process that she likened to applying for grad school?

“Gerrymandering is evil!” she said.

She regards her work on the 2010 commission as one of the most meaningful things she’s done in her life.

“Gerrymandering has led to extreme partisanship, which we are seeing all over the country right now, and it means that government can’t get the work of the people done. I feel that we played our part in fixing that, in California at least.”

Today she’s often on the road to other states evangelizing the value of independent redistricting commissions. Her last stop was Pennsylvania, a state so plagued by gerrymandering that the contours of one district earned the nickname “Goofy kicking Donald Duck.” (The state’s congressional map has since been redrawn by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court.)

But even while California touts its commission approach as insurance against partisan shenanigans, the state’s second crack at trying to field a panel of anti-gerrymandering gurus hasn’t been so easy. The shrunken pool of applicants for the next panel, which will draw lines after the 2020 census, skews more white and male than the state. Latinos are particularly underrepresented.

In pursuit of a diverse, qualified pool, the state extended the first deadline. Then it extended the second deadline.

“We act like ‘Oh my gosh, the problem is the deadline. The problem is people didn’t know’,” said Mike Madrid, a GOP consultant. “We should not fool ourselves into believing that that’s going to solve the problem because it’s not.”

Madrid called the extensions a patchwork solution to a larger problem: Latinos aren’t civically engaged because they tend to have limited access to economic mobility. It’s not surprising, he said, that an ethnic group that typically loses in California’s political system would not be engaged. If the system does nothing for them, why participate at all?

“They’ll extend the deadline and they’ll do outreach and they’ll throw some money at trying to cover up the glaring problem and you know they’ll stumble towards getting something representative,” he said.

More than 17,000 Californians were considered tentatively eligible to be a part of the 2020 anti-gerrymandering squad. That means as long as their info was accurate once double-checked by the auditor’s office, they’ve reached the next level: a step that includes several essay questions and three letters of recommendation. The deadline has been extended to Oct. 13.

But here, things get dicey. So far more than 700 applicants have turned in their supplemental questions. But completed applications, which includes the letters of recommendation, have dropped to less than 400.

From the final applicant pool culled by a panel of auditors, State Auditor Elaine Howle will randomly select eight commissioners by July 5, 2020. Then those eight choose six more.

Margarita Fernandez, a spokesperson for the State Auditor’s office said she expects a surge in applicants the final week before the deadline. The office has led online workshops to help applicants through the process. She said hundreds of viewers have tuned in to navigate the next step.

Political consultant Paul Michell of Political Data Inc. acknowledged that the process can be daunting. Nonetheless, he likes it better than the alternatives in other states.

“The process does make it hard to game the system. It would be nearly impossible for you to get any kind of significant number of commissioners in there that just happen to be the brother-in-law of the Speaker of the Assembly, or the sister-in-law of the president of the Senate or the cousin of the fundraiser for the governor,” said Mitchell. “That’s the kind of thing we see in commissions around the country. The way the process works and the independence of it from our politicians in California is kind of the greatest feature within this process.”

To Mitchell, the drop in applicants was to be expected, especially as the novelty of a brand new, shiny commission wears off. And the state’s extension of the first deadline, he said, triggered a domino effect that made an extension necessary for the second phase.

“YOU JUST CAN’T LET POLITICIANS DRAW THEIR OWN LINES.”

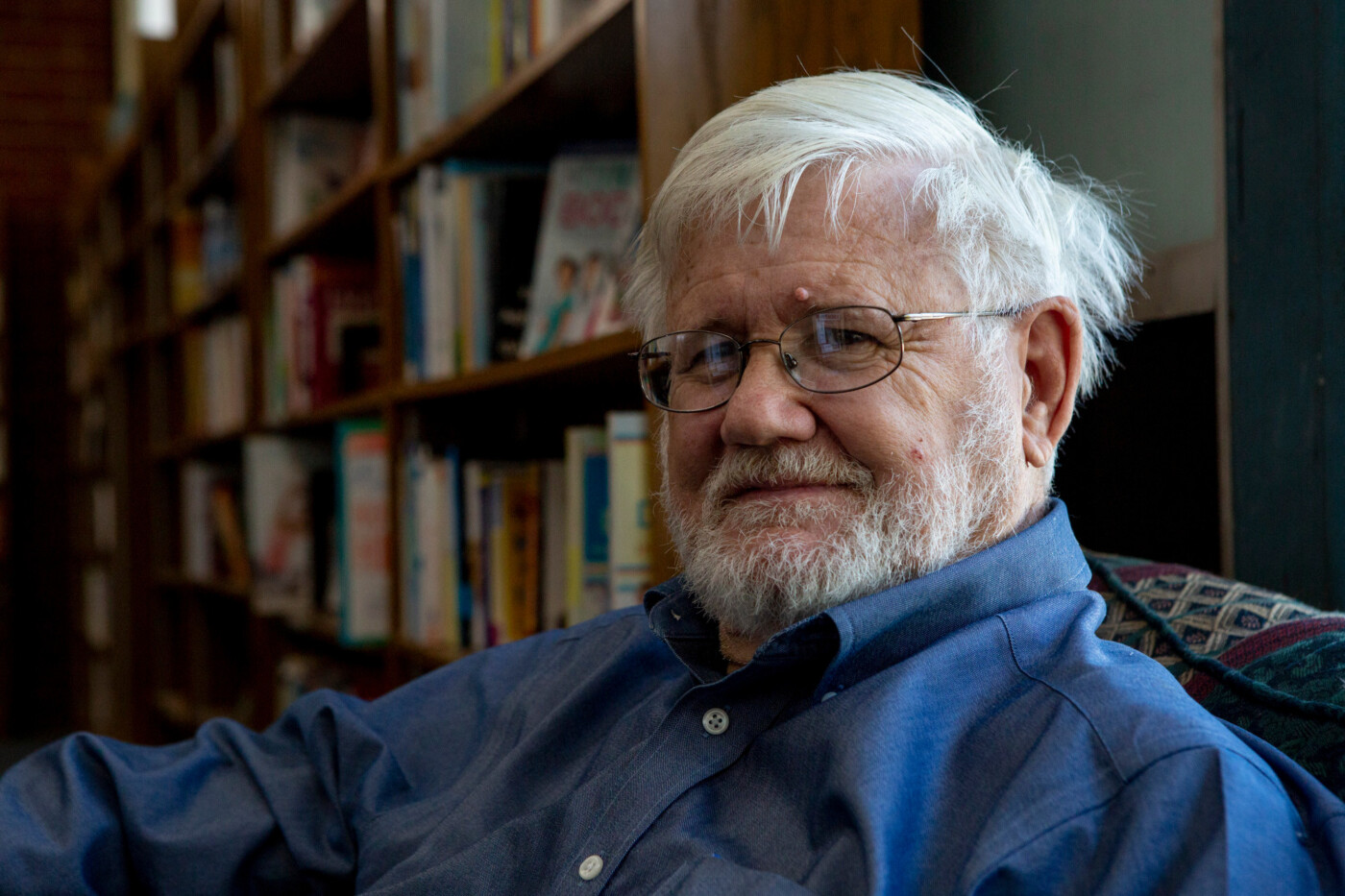

Stan Forbes

People now know what they’re getting into, said Stan Forbes, a Sacramento bookstore owner and member of the 2010 commission.

“If you have a paper due in college, how many people turned it in early? Nobody,” he said. “So when it gets to be two days before the deadline, then I might get more nervous. But at this point it’s just human nature.”

Forbes said his own cynicism about politics motivated him to serve on the commission, despite the fact that his day job forces him to work long hours seven days a week.

“You just can’t let politicians draw their own lines. There’s too much self-interest,” he said. “They’re simply incapable of not exercising that self-interest.”

He said he doesn’t have a party preference but that working with other commissioners from political parties members wasn’t a problem.

“It was fabulous,” he said. “You had a group of really like-minded individuals. They just wanted the system to work and they wanted the public to have a meaningful vote.”

Which was the goal all along. One of the biggest supporters of the commission is former Republican Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger. He pushed for a commission before California voters approved a 2008 ballot measure creating one. And he continues to preach its value. Last year, while filming for his recurring role as a T-800 cyborg, Schwarzenegger made time to share what he truly wants to terminate: gerrymandering.

“We all know this is not the sexiest subject in town,” he said in an interview with The Atlantic last year. “It’s always about showing your passion and fighting for it. The worst thing you can do is sit on your couch.”

While taking a break from filming a new Terminator movie last year, he visited Colorado and Michigan to campaign for ballot measures creating independent commissions there. In both states, the measures passed.

As independent commissions become more popular, there is evidence that they are having the desired effect. Christian Grose, the academic director of the USC Schwarzenegger Institute for State and Global Policy, has conducted research showing that states with independent commissions tend to be fairer and more representative.

In California, “the statewide votes matched the outcomes somewhat more proportionally than we see in these other extreme gerrymandering states so in that sense the commission had an impact,” Grose said. “Similarly, Arizona has an independent commission that’s like California and they also had some fairly proportional vote and seat outcomes.”

Eligible applicants for California’s commission must be registered to vote since 2015 and not have changed their party preference since then. They also must answer “no” to questions designed to ensure they lack any conflict of interest, such as whether they’ve worked for a political party or campaign in the last 10 years.

Phase two includes four essay questions:

- Why they want to serve and think the commission is important

- What it means to be impartial

- Their appreciation for California’s diversity

- Any relevant analytical skills they possess

Once selected, commissioners receive a $300 stipend for each day they conduct commission business, plus expenses related to their duties.

Applicant Caroline Farrell, a Green party member who lives in Bakersfield, has no complaints about the vetting process. As a Green Party member from a conservative part of the state, she feels she would be a fair representative of the Central Valley.

“The idea is to find people who can put partisan ideas to the side and think more about what districts make sense for the state,” she said. “Personally, I think it would be really interesting to learn more about the different regions in California, the different issues, the different communities, the different ways people identify themselves with the place that they live.”

Learn more about California’s anti-gerrymandering squad here and take a look at the 2010 crew here.