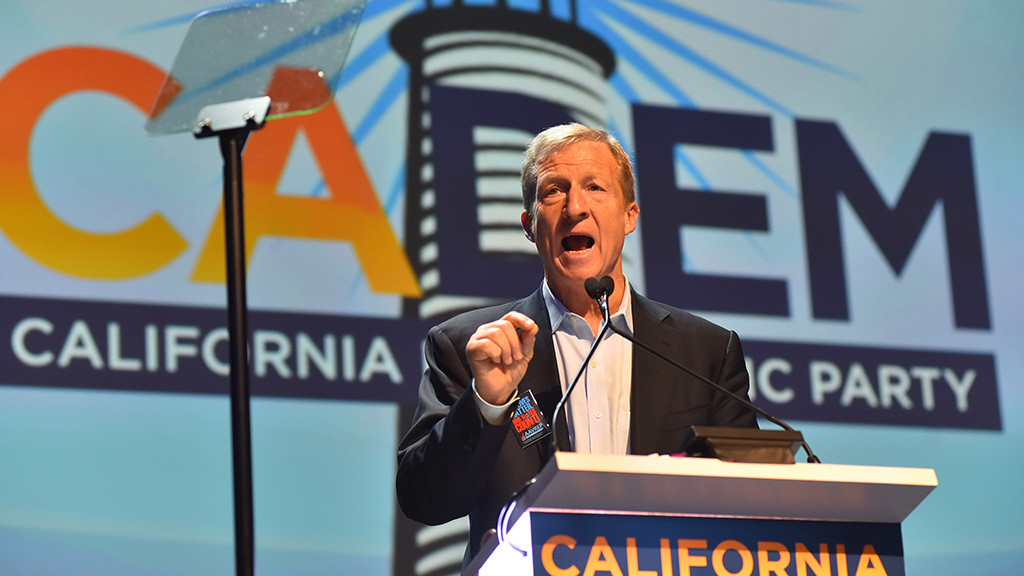

The newest (and 26th) declared Democratic presidential contender Tom Steyer—a billionaire hedge fund manager-turned-impeachment pushing money faucet for progressive causes—has a plan to fix our nation’s politics.

Ballot referenda, term limits, voting by mail. In short: make Washington D.C. look more like California.

In a new video released the other day, Steyer, who lives in California and has spent millions in support of Democratic candidates and progressive causes in the state, introduced a “Democracy Agenda” to combat the disproportionate political influence of corporations by giving voters “the tools they need to fix our democracy.”

These new tools include:

- A national referendum system that would allow voters to directly weigh in on two major policy debates each year

- Term limits for members of Congress

- Allowing every voter to vote by mail

- A push for more independent redistricting commissions tasked with drawing congressional electoral maps, as a way to end partisan and racial gerrymandering.

If that all sounds familiar, you might be a Californian.

Though the Steyer campaign has not yet responded to a request for more information about these proposals, many would require changes to the U.S. Constitution and dramatically alter the country’s system of governance. They also are staples of how things work here in the Golden State.

California votes have been setting state law via the ballot box since 1911 (though as our multi-page ballots attest, we are not limited to just two each year).

Likewise, the current district map for state Assembly and Senate races was drawn by an independent commission, state lawmakers have been term-limited since the mid-1990s, and more than half of California voters vote by mail.

That raises the obvious question: how have these worked out in California?

Ask most voters and the answer is, “pretty well.”

“California voters, every time we ask about the initiative process, have a very favorable response,” said Mark Baldassare, president of the Public Policy Institute of California, which regularly surveys the state. “They overwhelmingly say it’s been a good thing and an important check and balance to the governor and the Legislature.”

(Citizens of California can gather signatures to place two types of measures on the ballot: referenda, which allow them to affirm or reject existing law, and initiatives, which propose new laws. It’s not entirely clear what form Steyer’s proposal would take.)

Term limits are more of a mixed bag. Voters first placed a cap on how long members of the state’s Assembly and Senate can serve in 1996, but then lengthened the maximum tenure in either house in 2012.

Still, generally speaking, said Baldassare, “they’re favorable towards the idea of placing limitations on legislative power given their sense of distrust of government.”

The adoration for these approaches isn’t universal. Voter-enacted caps on the state’s ability to tax, spend or make budgetary changes have made “ballot-box budgeting” unpopular with many progressives.

There’s an irony to that, said University of California San Diego political scientist Thad Kousser, given that Steyer is one of the country’s most vocal supporters of impeaching President Trump.

“If you ask the people who he’s out at dinner parties in San Francisco with what they love about California, these would not be the top items,” he said. “These would be the things they complain about.”

The push for term-limits, for example, typically comes from the right. Former House Speaker Newt Gingrich included that in his “Contract for America,” the policy agenda he introduced before he led Republicans to a sweeping victory in the 1994 Congressional elections. President Donald Trump also endorsed term limits during his 2016 campaign.

Asked how she felt about being on the same side of a political issue as Tom Steyer, Harmeet Dhillon, Republican National Committee member from California, said the proposal “ignores our U.S. Constitution and tramples over states’ rights.

“I don’t think there’s any method to this madness except getting attention, which he’s clearly getting,” she said.

Would they accomplish Steyer’s goal of limiting the political influence of corporations?

Kousser noted that term limits do reduce the ability of special interests to develop longstanding relationships with lawmakers—but they also limit lawmakers’ ability to gain expertise, making them more dependent on outside experts, often lobbyists.

And when voters are asked to consider ballot measures, corporations and unions often have the loudest voice in those campaigns.

“The undeniable reality,” Kousser said, “is that there are hundreds of millions of dollars of corporate money in ballot campaigns in California now.”

Many of those millions have come from Steyer himself. In the lead-up to the 2016 election, for example, Steyer spent $13.2 million of a total of $22.4 in total political spending that year. He also gave $3 million to his political funding committee, NextGen California.

In today’s ad, he cites his experience bankrolling campaigns to raise taxes on millionaires (Prop. 39 in 2012) and hike taxes on cigarette sales (Prop. 56 in 2016), as well as his effort to preserve the state’s cap-and-trade program by funding the defeat of Prop. 23—all proof, he contends, that “together the American people can fix anything.”

The ability of monied interest groups to make use of a national referendum system could be tempered by capping the amount that corporations and rich individuals can spend on campaigns. That proposal made it into Steyer’s “Democracy Agenda” too.

But strict campaign finance caps—along with term-limits and a national referendum—would require amending the U.S. Constitution. And even for a man with Steyer’s resources, that’s a gigantic undertaking.