On the verge of retirement after years in the Central Valley, Bay Area native Daphine Lamb-Perrilliat just wanted to come home. Struggling with medical issues and the loss of a house she had purchased in Stockton, Lamb-Perrilliat was longing to return to the comfort of friends, family and the place she grew up.

It was during the last big recession, after the housing market crashed, when foreclosures were as common gridlock on state Highway 99. Eventually in 2014, Lamb-Perrilliat was able to move back to the Bay Area, where she stayed with a friend in West Oakland for a year and a half while she searched for a permanent, affordable home.

“I did not want to spend over half of my retirement on housing or rent, and because of my situation and where I am in my life today, I did not want to be in a position where I rent somewhere and investors come in and buy the property and I have to move or the landlord raises the rent too high,” Lamb-Perrilliat said.

“I wanted to establish myself,” she said. “To stabilize myself in housing.”

[Finding stable housing is] easier said than done, especially for Oakland’s low-income residents, people on fixed incomes and, disproportionately, people of color.

The lack of affordable housing in the city seems cruelly ironic, given the recent development boom in Oakland, where large construction cranes dominate the skyline and many streets are a confusing warren of building-related detours and closures.

And while housing and tenants rights activists say Oakland is doing more than many Bay Area cities to plan for and build affordable housing, data shows that it’s lagging far behind when it comes to filling the need.

“The city of Oakland is a relatively good actor when it comes to producing affordable housing but it’s been extremely reluctant to get in the way of market-rate developments, and we find that frustrating.”

Gloria Bruce, the executive director of East Bay Housing Organizations

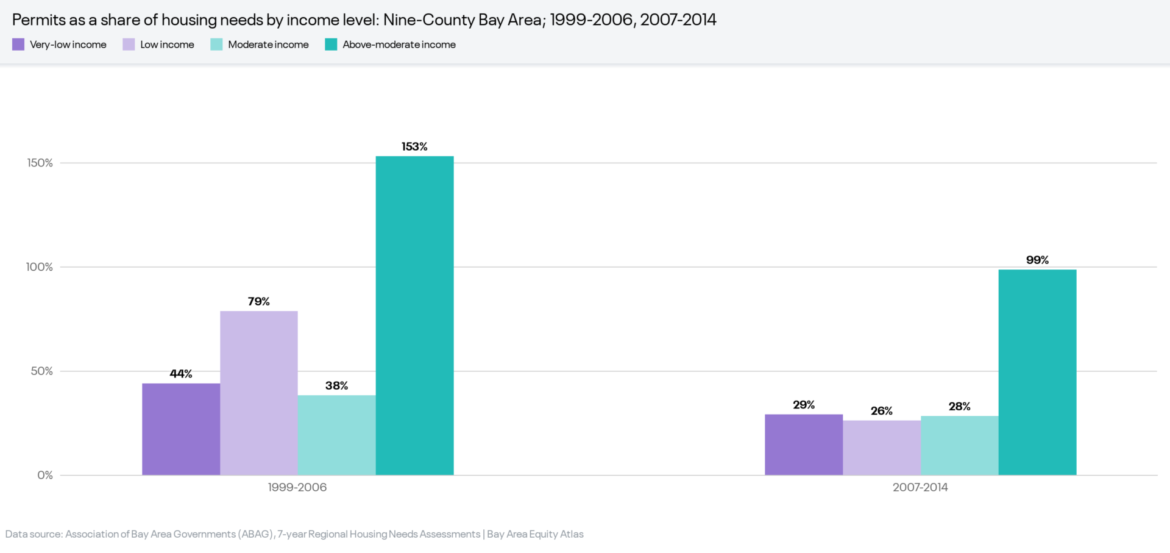

For example, between 1999 and 2006, Oakland issued building permits for a whopping 267 percent of the above-moderate income housing it needed as projected by the Association of Bay Area Governments, according to data compiled by the Bay Area Equity Atlas, an Internet database that tracks the state of inequality across the Bay Area.

During that same period, the city also issued permits for just 27 percent of the very-low income housing it needed, 71 percent of the low-income housing and 8 percent of the moderate-income housing, according to the atlas.

“Under Jerry Brown [Oakland mayor from 1999 to 2007], there was an explicit agenda to bring in higher income people and market rate housing,” said Gloria Bruce, the executive director of East Bay Housing Organizations, a non-profit group dedicated to helping provide affordable housing to low-income communities in the East Bay.

At the time, Oakland didn’t charge developers fees that the city could then use to build affordable units and, unlike many cities in the region, it has never had an “inclusionary housing” ordinance, which requires market-rate developers to include affordable housing in their projects as a condition of city approval.

“There was a concern that an inclusionary housing policy would scare away development in a city that desperately needed it,” Bruce said.

Still, over the next seven years and in the wake of the collapse of the national housing bubble, the city issued a greater percentage of its needed affordable housing permits than it did for above-moderate income permits, according to the atlas.

During that time, it issued building permits for 67 percent of the very-low income housing it needed, 18 percent of the low-income housing, 1 percent of the moderate-income and 31 percent of the above-moderate income housing.

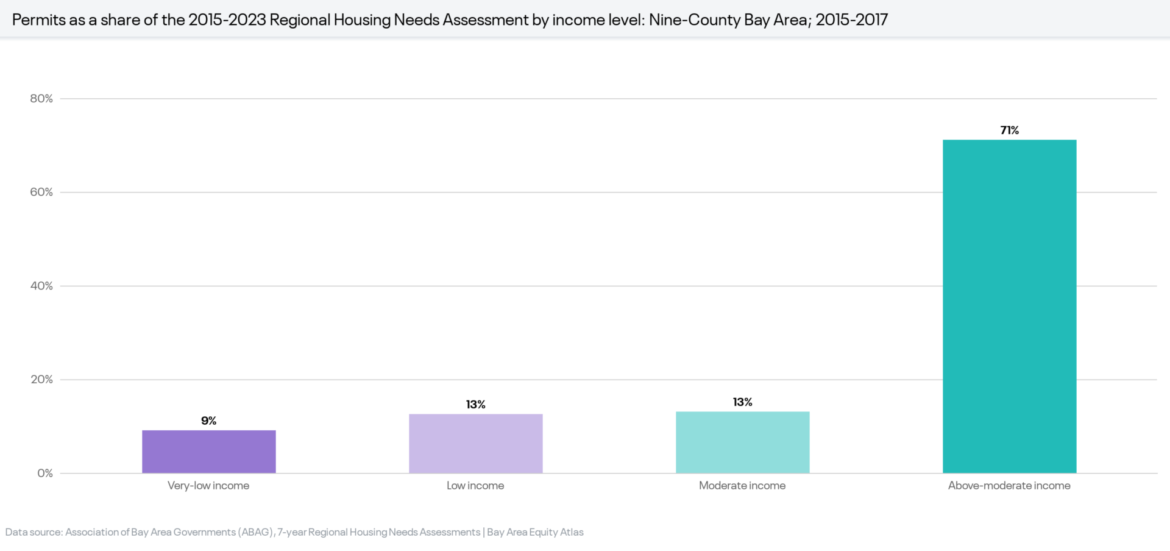

But then between 2015 and 2017, during a massive building boom, it appears as if Oakland’s priorities again swung back to the construction of market-rate homes, as it issued permits for 85 percent of its need projected for above-moderate income housing while issuing just 15 percent of the needed permits for very-low income housing, 5 percent for low-income and zero permits for the moderate-income housing need for the seven-year period between 2015 and 2023, according to the atlas.

The prevailing attitude has been that “if we just build a bunch of housing, that will solve the problem,” Bruce said. “Well, of course it doesn’t. The market won’t solve the problem for low- or moderate-income people. About 7 percent of what’s getting built is affordable.”

Due to the lack of affordable housing, rising home prices and gentrification, among other things, the estimated median market rent in Oakland climbed by roughly 72 percent to $2,960 between 2011 and 2017, according to the atlas.

That’s more than half the gross monthly pay of a household with two full-time workers on Oakland’s $13.80 minimum wage.

And from 2000 to 2015, the percentage of renters in Oakland paying more than 30 percent of their income on housing rose from 44 percent to 55 percent.

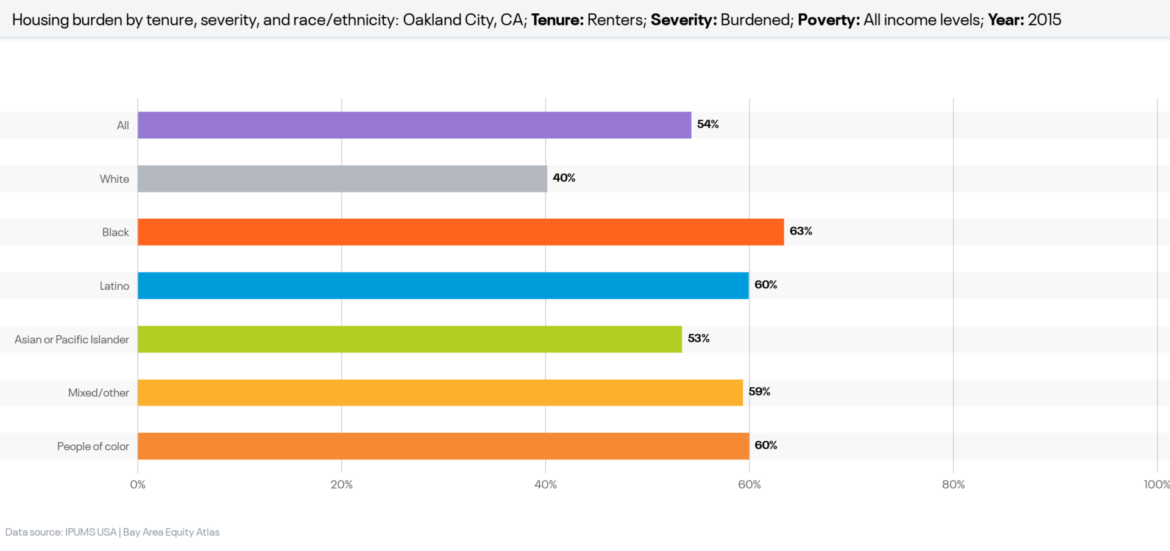

This housing burden falls disproportionately on communities of color, with 63 percent of African American renters, 60 percent of Latinos and 53 percent of Asian or Pacific Islanders paying more than 30 percent of their incomes on housing – compared to 40 percent of white renters, according to the atlas.

Also, atlas data shows that 92 percent of Oakland’s black residents live in neighborhoods that are either being gentrified or are at risk of gentrification, as are 94 percent of Latino and 88 percent of Asian or Pacific Islander residents.

To highlight the city’s systemic housing inequity, Bruce notes that when 35 affordable apartments recently opened in a neighborhood near Mills College, 4,000 people applied for a unit.

“That’s a very typical ratio,” Bruce said. “Any notion that we’ve done enough is just not the case, so we’re saying we cannot hinge our strategy on only building market rate housing.”

For people like Lamb-Perrilliat, finding an affordable unit is largely a matter of persistence and luck, since even after finding an available home and qualifying for the chance to move in, most prospective tenants are then subjected to the whims of a lottery draw.

“It’s pretty much a lottery so you just take your chances,” Lamb-Perrilliat said. “It can be looked at as a numbers game. You keep filling out applications and keep putting your name on different lists so that you can be considered for some type of housing.”

That’s exactly how Lamb-Perrilliat became one of the city’s lucky few when she was selected to move into an affordable one-bedroom apartment in a nice neighborhood near Lake Merritt.

In an effort to increase those kinds of success stories, on June 25 the Oakland City Council passed a two-year budget that includes nearly $30 million for affordable housing development, renter assistance and homeless programs.

Some of that money comes from Oakland’s Measure KK, a $600 million bond measure voters overwhelmingly approved in 2016 to improve the city’s infrastructure and build affordable housing.

Some of the money comes from the state and is subject to grant requests from the city and a smaller amount – $5 million – comes from the “Affordable Housing Impact” fee Oakland started charging developers three years ago.

Of the total, $12 million is earmarked for the city’s new Preservation of Affordable Housing Fund, which will be used to acquire and rehabilitate properties with 25 or fewer units in order to convert them to or retain them as affordable housing.

Oakland City Councilwoman Nikki Fortunato Bas, who led the effort to create the new fund, said the idea is to encourage homeownership and keep existing homes out of the hands of house-flippers and speculators.

“One of the best ways we can stop displacement is to organize people who are tenants to purchase their homes,” Bas said. “I’m really interested in this idea of growing homeownership as well as getting more affordable housing off the speculative market.”

Bas notes that 88 percent of Oakland’s existing housing stock is made up of buildings with 25 or fewer units, so it’s a critical target area for government and nonprofit affordable housing programs.

Also, this strategy is attractive since the cost to build a brand new affordable unit clocks in at roughly $600,000, while it costs about $250,000 to acquire and preserve an existing unit as affordable, Bas said.

While the new fund is an important step in the right direction, Bruce says the $12 million is a “drop in the bucket.”

“We estimate that there is as much as $100 million in impact fees that should be coming in,” Bruce said.

The city claims that it is doing an assessment of the fees collected to date, Bruce said, but she fears that the process could drag on.

“We need them to do it quickly because the people in Oakland can’t wait,” Bruce said.

Housing activists are also concerned that Oakland has yet to implement a policy to require affordable housing in projects on city-owned property. But while Oakland may be lagging behind on developing policies that require market-rate developers to contribute to the city’s affordable housing stock, Bas notes that there is a growing realization at City Hall that, by dint of the current construction boom, it finds itself in a pretty strong negotiating position.

“One of my observations is that Oakland has had this complex of being a stepsister of San Francisco and fearing that development will go away if we ask for too much. I think those days are over.”

Oakland City Councilwoman Nikki Fortunato Bas