Shanti Brien

I sat in a community workshop last week — in a molded linoleum chair in the Veteran’s Hall — talking about race and identity and inclusion. The presenter brought up a slide on the demographics of my small Northern California town of 11,000 people. Nineteen Native Americans live here. Not 1,900. 19! In pre-colonial America, experts believe there were between ten and eighteen million. By the 1890’s the population had been decimated to 250,000. And now 19. A young woman — blonde and attending for extra credit for her Civics class — was the first in our small group discussion to respond. She had noticed the bleakness of nineteen, too. “That’s just so sad,” she said.

During the next break, I chatted with a man about our town, my tribe, and my sadness about that less-than-twenty number. He asked me “How important is being Native American to your family”? This is the second-most question I get when I tell people I’m Native. It’s hard to answer and I immediately thought about asking the Asian woman next to me how important being Asian was to her. I digress.

My answer: It’s everything. And sometimes it’s nothing. Identity is individual and indivisible. My identity as a woman, a mother, an attorney-activist, and a Native person share equal importance…on most days. Pretty much every decision I make I consider my children. They are only a split second from my complete attention. Sometimes I’m without my kids — hiking or traveling for a workshop with 100 police officers who would rather not hear me talk about active listening — and even then, I’m enjoying the break from them but it doesn’t make me less of a mother.

In yet another workshop I attended this year, I met a man — an older Asian man, public servant and technology specialist — who explained this concept well. He didn’t think a lot about being Asian, he said, especially in the Bay Area. But when he went to Mississippi for a wedding, and a good-hearted guest said he must be “good at Kung Foo, huh?” his Asian-ness just slapped him across the face. That’s the feeling I get when someone asks me how much Indian I am. Or they ask if I grew up on a reservation. Or they ask, “like Pocahontas!?”

And these questions used to fill me insecurities and embarrassment. The answer “not enough” always bubbled up in me. I didn’t grow up on a reservation, I don’t wear ribbon dresses or eagle feathers. But just as my left hand or my right lung is equally important to my body, being Native is essential to my body, to my drive and commitments, to my family and our history.

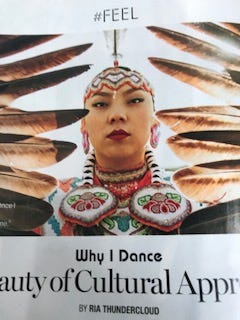

There have been times when I wished I looked like this. (Photo cred: Glamour. And btw, thank you, Glamour for including articles about Native women in your magazine.)

My family is Muscogee/Creek. Most of the tribe was marched from their home in Alabama and Georgia to “Indian Territory” in chains, deprived of food, and battered with whooping cough, typhus, dysentery, and cholera. Almost a quarter of the people died in the process. Around 1900, the United States stole the Indian Territory from the Natives, forcing them onto 160 acres per family. My family still has that land in Oklahoma with its pecan trees, annual flooding and falling-down barn. The feeling of connection to the earth while simultaneously being ripped from it and floating, unmoored without a home, is the feeling of being Native. Sometimes when I run or hike, I feel the earth hold me up and even push me forward. I bet I’ve run or hiked almost 15,000 miles in my lifetime –in Oklahoma and in Oakland, the Sierras and the South — and though I’ve wandered too, I feel connected and strong.

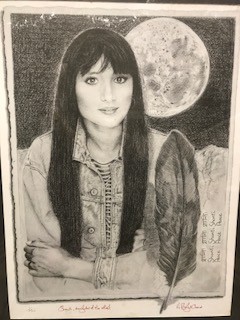

This is a pencil drawing of me done by my father. He obviously has a highly romanticized, quasi-princess thing going on.

But there is sadness in our bones and cells. I hear my father absolutely consumed in despair over the genocide of our people and all Native peoples and I know one cannot separate a modern diagnosis of depression from the imaginable loss that he and I have inherited. Sometimes I have to laugh though and think of other ways I look like an Indian: sarcastic and resilient, drunk and hard-working. I enjoy a good trip to the casinos in Las Vegas as much as dancing to drums at pow-wow. In college I got drunk at frat parties as much as I wrote poems full of anger against neo-colonialistic tribal enrollment policies. I am a feminist and an activist, an environmentalist and a pacifist. Are they part of a Native American world-view? Obviously yes and maybe not.

I am Native. Not full-blooded but I am full citizen of the Muscogee Nation, the fourth largest tribe in the country. I have the right to vote in tribal elections and a smattering of other benefits like burial assistance. I don’t agree with citizenship based on a certain blood quantum; it seems like just another way to disappear us. The Muscogee Nation bases our citizenship on whether we can trace our ancestry back to a family on the list created when the 160 acres were allotted. It seems ironic to base our citizenship, the very identity of our people, on a policy of the colonizer that explicitly sought to wipe us off the face of the earth.

And yet I persevered to get my kids enrolled as members through years of applications, notarized statements, official birth certificates, more official certified certificates, and record searches. Because our existence is the most Native thing we can do. Just to stand up in a group and say loudly, “I am Native American,” “I am a enrolled member of the Muscogee Tribe” is to do something powerful. We exist, this tells the world. You failed in destroying us. We may not look like Pocahontas or wear beads and turquoise all the time, but we are here. We are here, with thousands of years of memories and pain and celebration, and we are important.