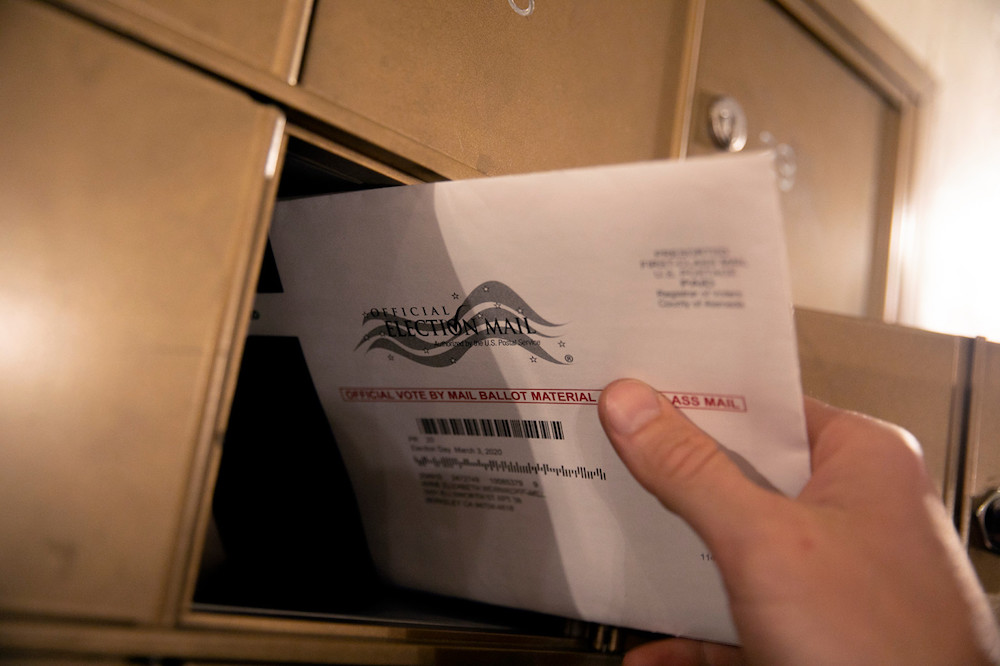

This coming November, every one of California’s more than 20 million registered voters may receive a ballot in the mail — whether they ask for one or not. In fact, many election administrators and advocates say it’s inevitable.

“It’s not a question of ‘if,’ said Kim Alexander, the president of the California Voter Foundation. “But ‘how.’”

California is already ahead of the curve when it comes to voting from home. In the March primary election, 75% of voters got a ballot in their mailbox. But the exigencies of social distancing are putting pressure on state lawmakers to round that up to 100%, ensuring that every registered voter has the option to cast a ballot without having to physically crowd into a polling place.

A bill from Palo Alto Democratic Assemblyman Marc Berman would ensure just that. But with most state legislators sheltering in place until at least early May, all eyes are on the governor who, with an executive order, could make the upcoming election an all-mail affair.

Earlier this month, Joe Holland, president of the California Association of Clerks and Election Officials and top election official in Santa Barbara County, sent Gov. Gavin Newsom a letter requesting that he ink a new edict, declaring the November contest an “all-mail ballot election.”

Even if mass gatherings are permitted in November — something Newsom says is unlikely — county election officials say time is of the essence. Ballots have to be ordered, voter rolls assembled, polling places secured.

“The consensus for November 2020 is that California is going to go all vote-by-mail — and we should. We don’t want to have a Wisconsin debacle,” Holland said, referring to the April 7 presidential primary where some voters reported waiting in line for five hours. Since then at least three dozen voters and polling workers in Wisconsin have tested positive for COVID-19.

The governor’s press office has not responded to a request for comment about prospects for a California all vote-by-mail election.

Even an “all-mail” election in California isn’t quite what it sounds like — it wouldn’t really be without a brick-and-mortar option. For those who need some extra help exercising their right to vote, state law requires counties to set up a certain number of in-person polling places.

Through Holland, the association also asked Newsom to grant them the authority to radically scale back that requirement. And therein lies the current rub.

Some advocates warn that an insufficient number of drop-off sites and vote centers could leave many voters — particularly those from underrepresented demographic groups — either unable to vote or stuck in long lines at the few remaining in-person locations.

“Waiving the state’s in-person voting standards will potentially disenfranchise tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of California voters,” union president Bob Schoonover, whose chapter of the Service Employees International Union represents tens of thousands of public sector workers across Southern California, wrote in a letter to Secretary of State Alex Padilla earlier this month.

Recent polling finds strong majorities of Americans believe voters ought to be able to cast their ballots by mail without an excuse — though results are split on whether a majority of Republicans feel the same way.

Like so many debates of the COVID-era, it’s a disagreement that pits constitutional rights once thought to be non-negotiable against the prescriptions of public health.

“We’re trying to find the right balance of response that gives voters as much choice as possible, but also keeps them safe, and frankly, which is also implementable in the short number of months that the counties have to gear up,” said California Common Cause interim director Kathay Feng.

The coronavirus pandemic has injected new urgency into the national conversation about voting by mail, with some states now making it easier for voters to cast their ballots while self-isolating at home — and others not, and getting sued for it.

Despite evidence that making it easier to vote remotely does not benefit one party over another, the debate has taken on a partisan bent.

Weighing in earlier this month, President Trump urged Republicans to fight “very hard” against the expansion of vote-by-mail opportunities, claiming without evidence that such a system has “tremendous potential for voter fraud” and that “for whatever reason” such systems don’t “work out well for Republicans.”

The president’s views notwithstanding, recent polling has found strong majorities of Americans believe voters ought to be able to cast their ballots by mail without an excuse — though results are split on whether a majority of Republicans feel the same way.

But in California, there is little debate in policy-making circles about the merits of vote-by-mail elections.

Throughout April, Secretary of State Padilla — the administrator in chief of the state election system and, like Gov. Newsom, a Democrat — convened roughly 80 election officials, experts and advocates. They met, remotely, of course, in daily conference calls to game out how California might hold a statewide election during a full-blown pandemic.

Subgroups splintered off to hammer out every last logistical detail. Would registration deadlines be changed? How will each voter’s language preference be determined? Self-adhering envelopes that risk gumming up ballot-counting machines versus those sealed by pathogen-packed spit — how should counties decide?

Jonathan Stein, a program manager for the Asian Law Caucus’ voting rights program, was part of that task force. He said there was unanimity on at least one issue.

“There seemed to be almost universal agreement that we need to send every single voter a vote-by-mail ballot,” he said.

The question is, what other options will be available too?

Election rights advocates say in-person polling places offer a vital service to voters who don’t speak English, who experience some kind of disability, who don’t have a fixed address, who recently moved or who simply don’t feel comfortable with or do not understand the vote-by-mail process.

“There are a lot of communities that depend on polling places and polling centers,” said Mike Young, political director at the California League of Conservation Voters. In California, in-person voters skew poorer, younger and less white than the average voter.

An insufficient number of polling places could jeopardize public health even further, Young added. Like Holland, he pointed to Wisconsin as a cautionary tale. “People are anticipating that this is going to be an insanely high-turnout election.”

California voting rights advocates seem to have at least the tacit support of the state’s top election official.

“I think people who need or prefer an in-person option deserve it,” Padilla told KQED earlier this month. “And so we’re going to have to work really hard with counties to ensure we maintain as much in-person voting as we can.”

But county registrars argue that such requirements may put voters and poll workers at unnecessary risk.

“Quite frankly if we had an election tomorrow I wouldn’t be within a hundred feet of a polling place,” said Holland in Santa Barbara.

There are also practical questions about space and staffing, both of which are severely limited by the pandemic. Polling places are often hosted in schools, senior centers, and the garages of private homes — most of which are likely off the table now. The typical poll worker is a retiree, a cohort particularly at risk of severe COVID-19 complications.

Santa Barbara County is preparing to reduce the number of in-person locations from the 86 that were open in March to around five. Holland’s office may use the registrar’s three offices and then try to secure a handful of additional sites and the necessary poll workers.

“I don’t know if I can find three other facilities,” he said. “I have 15 staff and that’s when they’re here and healthy and right now three or four are out sick.”

Assemblyman Berman’s bill said his bill does not yet address in-person polling site requirements, but that the “first move shouldn’t be to weaken existing in-person voting requirements.” He urged state and county officials to be “creative” in finding locations and staff.

In the meantime, he said, some additional guidance from the governor could be helpful.

Newsom has already issued an executive order mandating that all voters in two upcoming special elections receive ballots in the mail. Though the order “encouraged” counties “to make in-person voting opportunities available,” they were given the freedom to do so “in a manner consistent with public health and safety.”

The two elections, a Senate race in Riverside County and a congressional contest north of Los Angeles, is showcasing how counties may differ in how they administer elections during a pandemic. In the congressional race, split between Los Angeles and Ventura counties, there will be at least a dozen locations where voters can drop off ballots in-person.

In Riverside County, home to the special Senate district, there will be only two physical drop-off points and no polling places or vote centers where voters can have their questions answered or their errors corrected.

“That’s a perfect illustration of what will happen if we give election officials full discretion,” said Stein.