At Cabrillo College near Santa Cruz, Nikia Chaney stands out. You can spot her bright pink hair from a distance. She’s also the only Black professor out of the community college’s 165 tenured or tenure-track faculty.

“When I first got hired in 2019, I didn’t look up the demographics of the school or anything like that. I was just really happy I had a full time job,” she said. But after arriving on campus, she started to feel isolated. “You don’t have faculty members who look like you,” she said.

The California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office, the agency representing all 116 of the state’s community colleges, wants “to have the makeup of our faculty and staff mirror the student population we serve,” said spokesperson Melissa Villarin. For years, the office has tried to increase diversity as state legislators pumped money into attempted solutions.

Faculty diversity has increased slightly over the past 15 years, but a report the chancellor’s office issued in November acknowledged that “progress remains slow.”

Villarin said that there is no single explanation why, but that the problem often lies in recruitment, hiring, and retention. For example, the application website for community college jobs is “outdated” and panels that select candidates often need to be more diverse and better trained, she said.

In a separate state audit released this spring, some college districts said it’s hard to find qualified professors when there are few people in their communities with the necessary graduate degrees. In other cases, the report said, faculty find “higher-paying positions elsewhere.”

“This is a nationwide problem. When everybody is focused on trying to diversify your faculty, it’s going to be your Harvards and Yales who are going to pay you the most,” said Olivia Cheche, a program associate in higher education at the nonprofit think tank New America.

The largest discrepancy across California’s community colleges is for Latino faculty. Latino students represent nearly half of community college students but less than 20% of tenured or tenure-track faculty are Latino. The same disparity holds true for Latino administrators.

To help, state lawmakers and the chancellor’s office have introduced new hiring initiatives and poured an estimated $90 million into reforms in the last 20 years. Half of that money has come in the last three years. But the audit said college districts still have a ways to go.

‘Hostile and unwelcoming’ for Black students

At her first English department meeting, a coworker handed Chaney a 2018 report about diversity at the college. “African-American students experience Cabrillo College as a hostile and unwelcoming environment,” the report said, citing interactions with other students, faculty, and administrators. These students also noted a lack of representation across the school.

“It made my heart sink,” Chaney said.

Numerous studies show that a more diverse faculty benefits students and can even help to close achievement gaps between white students and students of color. Using years of data from DeAnza College, a community college in Cupertino, one study found that students who are Black, Latino, and Native American/Pacific Islander get better grades, were more likely to pass a course and less likely to drop classes when they had a professor who looked like them.

“It’s that idea of having a role model that looks like you. That might be the encouragement a student needs to pursue a higher education,” Cheche said.

Statewide, the report from the chancellor’s office shows the percent of tenured or tenure-track community college professors who identify as Black is about the same as the percent of Black students: between 5% and 6% in 2022, the most recent data available. The percentage of community college administrators who identify as Black is even higher.

But representation is uneven. At Lassen Community College in Susanville, there are no Black full-time faculty, even though more than 1 in 10 students are Black. In San Luis Obispo, and at other rural colleges across the state, similar disparities persist.

Last year, just over 1% of Cabrillo College students identified as Black, according to data from the chancellor’s office. Chaney is committed to helping those students.

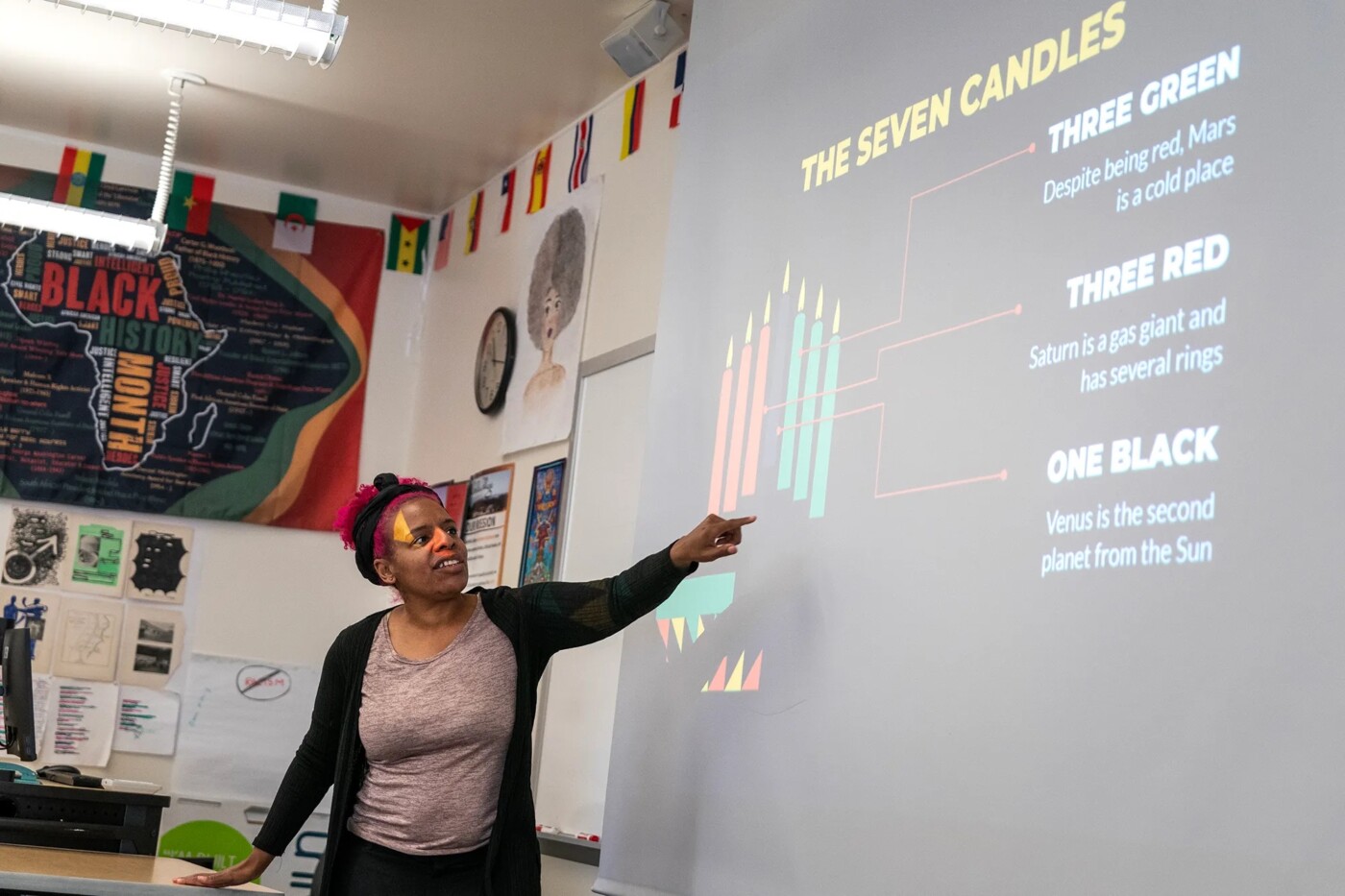

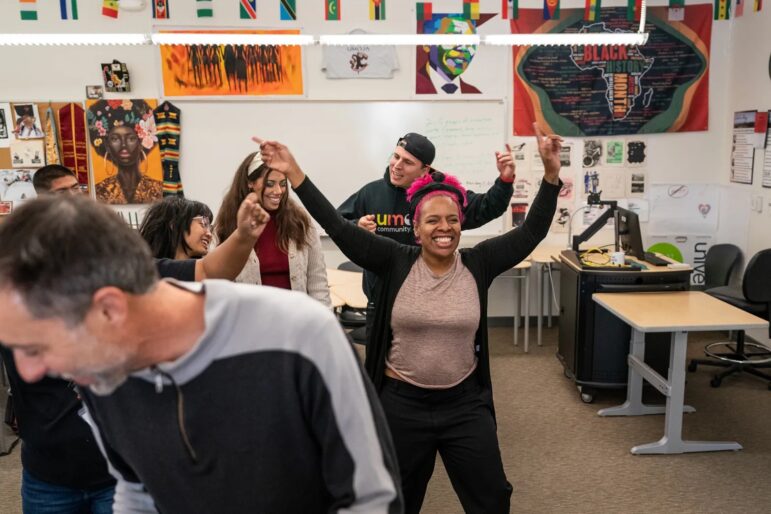

“I know myself as an educator. I’m not going to be able to be in a place and not do anything. It’s what keeps me here, but I also really love it,” she said as she set up a classroom for an end-of-year celebration for students in Umoja, a state-funded academic program to support Black students, though anyone can participate. Umoja has existed on other campuses for years, but Chaney helped launch the first iteration at Cabrillo College last fall.

Standing underneath a poster for Black History Month, she turned on the music to the sounds of a drum circle. “Do I have some volunteers who are going to get up and dance with me?” she said as people slowly trickled in. About 15 students and staff attended the event, most of whom were not Black.

Kyla Kientzel, who is biracial and an Umoja student, said she appreciates the efforts that Chaney is making for students like her. “It kind of makes me more comfortable when there’s people that look like me around. I’ve never had a Black teacher before,” she said. One time in Chaney’s English class, Kientzel wrote about her first name, which was given to her by her father, who is Black. “I get to write about my experiences, and she understands,” Kientzel said.

Catching a flight to work

Cabrillo College has two campuses, one in the wealthy seaside community of Aptos and another, just 20 minutes away, in the inland farming town of Watsonville. About 80% of residents in Watsonville identify as Latino, and Latino students there said it had a “welcoming” and “very communal” climate in the campus’ 2018 diversity report. In Aptos, which is 75% white, that welcoming spirit fades, the report said.

Across both campuses, about 18% of faculty identify as Latino, compared to roughly 46% of Cabrillo students.

The district is well aware of the lack of diversity, particularly when it comes to Black faculty.

“My heart really is there for Nikia (Chaney). It’s not right and it’s something we need to address,” said Adam Spickler, a trustee of the community college district’s board.

“I feel like we’ve done fairly well increasing diversity in other ways. But we need to turn that attention to African-American faculty — no doubt.”

As an example of improvements, Spickler pointed to increased diversity among the college’s administration. Out of the 23 administrators, three are Black and four are Latino this year.

Spickler said the overall lack of diversity isn’t surprising given the demographics of Santa Cruz County. While the region has large and growing Latino and Asian communities, about 1.5% is Black, according to the most recent census data

Growing up in the area, and now as a student, Kientzel doesn’t always feel safe. “When I’m by myself, I get treated fine, but when I’m with my brothers, we get followed in stores. We always make sure we have our hands out of our pockets, so they don’t think we’re trying to steal anything,” she said.

Mikias Abesha is the president of Umoja club and a third-semester student at Cabrillo College. But as an international student from Ethiopia, he finds the lack of diversity isn’t the only challenge.

“Everything is different,” he said. “In my first semester, I did not understand any of my teachers.”

His first language is Amharic. He said Umoja was a respite for him, where he met advisors who made him feel at home. Now, his goal is to transfer to UCLA. “Los Angeles will be much more diverse,” he said.

For Chaney, the experience was untenable. She said her daughter was one of only a few Black students in her elementary school and was often bullied by other students. After living in Santa Cruz County on and off for two years, she decided to move back near friends and family near San Bernardino, where the Black community is also much larger.

“I need to be in a town where people look like me,” she said. Now, she flies in once a week for classes and campus programs.

Millions spent to diversify faculty

Legally, public colleges can’t consider the race or ethnicity of a job candidate because of a constitutional amendment California voters passed in 1996 that banned affirmative action. Voters reaffirmed the ban in 2020. But the chancellor’s office and state auditors agree that colleges can use other means to achieve the same goal — such as providing diversity training to all staff members involved in hiring, so they can better recognize and correct for their own biases.

In 2021, the chancellor’s office required college districts to develop a plan for promoting diversity in hiring. Villarin said 68 out of 73 districts have submitted a plan to the chancellor’s office as of Oct. 1, the final deadline. She said the remaining districts include Los Angeles and Glendale, as well as the districts that represent colleges in Eureka, Stockton, Cupertino, and Los Altos. They will submit their plans in “the coming days,” she said.

Colleges are also required to analyze the demographics of their job applicants, but the state audit found only one out of the four community college districts surveyed had done so. Fermin Villegas, a deputy counsel for the chancellor’s office, said his team would be providing “more oversight and monitoring” in the future.

Of the millions of dollars the Legislature earmarks each year for efforts to diversify hiring, most is sent to the state’s 73 community college districts, which then distribute it to the 116 community colleges. Last year, most districts received about $139,000, Villarin said. Reports show the districts used the money to mentor and train potential and current faculty, among other efforts.

Following recommendations from the chancellor’s office, Cabrillo College is trying a “cluster” model: hiring for eight new positions, simultaneously, focused on the candidates’ qualifications in their academic fields and their commitment to serving marginalized students.

One advantage of cluster hiring is that it can help avoid scenarios in which one faculty member becomes the token person of color, according to a memo from the Academic Senate for California Community Colleges.

Chaney said she’s not the only advocate for Black students on campus, and pointed to the work of a few Black and Latino administrators and staff who support students in other ways. Many arrived at the college within the last year or two and live in the county.

Chaney said it’s valuable to have mentors who live in the community but it’s also important to have faculty who know Black culture, even if, like in her case, those two aren’t the same.

After the Umoja event ended, Chaney didn’t have time to clean up so her colleagues carried the leftover food and supplies to their cars. “I’ve got to run,” she said, hugging each person as she said her goodbye. She had to drive to San Jose to catch a flight home that afternoon.