Californians in two industries are set to get new minimum wages just for them next year, and that could lead to pay bumps for other workers, too.

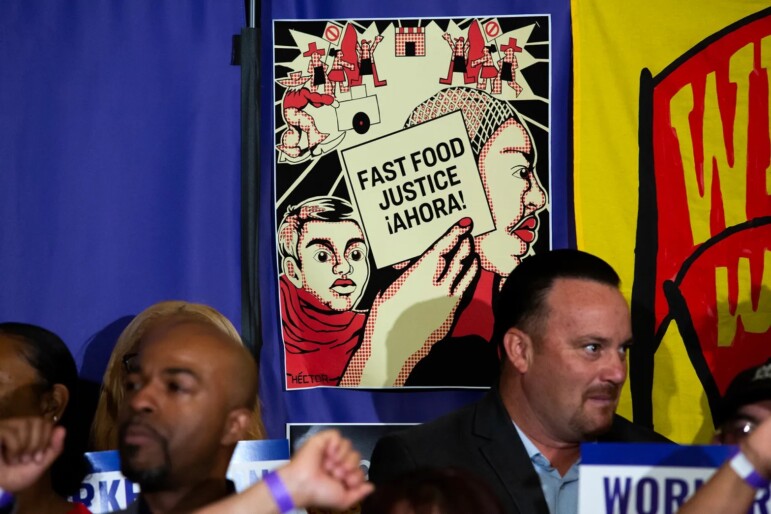

Gov. Gavin Newsom this year signed two union-backed bills that will boost fast-food and health care workers’ minimum wages.

California-based fast-food workers for chains with 60 or more locations around the nation will earn at least $20 an hour beginning in April, $4 higher than the overall state minimum wage of $16 that will be effective Jan. 1.

In June, health care workers will earn a minimum of $18, $21 or $23 an hour, depending on what type of facility employs them and where they work.

The industry-specific wage increases reflect a shift in unions’ strategies at the Capitol. After the Great Recession, labor groups led campaigns that resulted in then-Gov. Jerry Brown signing a law in 2016 that put California on a path to a $15 minimum wage. That law included inflation adjustments, which is why the minimum wage is higher today.

The two new laws are expected to trigger pay increases for about 900,000 Californians, some of whom are earning more than minimum wage today.

They are going into effect in a competitive labor market that has seen employers, especially small businesses, struggling to hire and retain workers. California’s unemployment rate is at 4.8%, which is higher compared with the federal unemployment rate of 3.7% but is near a historic low.

The new fast-food minimum wage could push up pay for other restaurant and food workers, experts say.

In a tight labor market, “other food-services companies will likely have to increase wages in order to retain workers in a sector in which chronic understaffing, and the stress and burnout that causes among remaining staff, is already a problem,” said John Logan, professor of labor studies at San Francisco State University.

Others say the industry-specific minimum wage could have ripple effects in other industries.

Keith Miller owns three Subway sandwich shops in Northern California and is spokesperson for the American Association of Franchisees & Dealers, which opposed the fast-food worker legislation. The law passed with support from major fast-food chains, which gained assurances that unions would drop an initiative that would have made the chains liable for their franchises’ labor violations.

Under the law, Miller said, franchisors like McDonald’s or Subway avoid responsibility but franchisees like him will bear the costs of paying higher wages.

Miller questioned why fast-food workers were singled out as needing a minimum-wage increase, and added that it could affect industries such as retail. He said retail workers might switch over to fast food if they can make more money there, or retailers might need to raise their workers’ wages.

“It’s kind of a fallacy that this impacts only fast-food workers,” Miller said. “It kind of creates a market rate. In effect, the minimum wage for a lot of people will be $20.”

California voters in November will see a ballot initiative that would raise the state minimum wage to $18 an hour. It’s backed by billionaire Joe Sanberg.

Workers in other industries, meanwhile, are fighting for higher minimum wages, too. In Los Angeles, a proposed ordinance would institute a $25 minimum wage for workers in the tourism industry before the 2026 World Cup and the 2028 Olympics, which would rise to $30 an hour by 2028.

Jovan Houston, an airport security worker at Los Angeles International Airport, said she has been working there for six years and makes $19.78 an hour. She said a boost in wages would be “extremely” helpful for her and her 13-year-old son. They live with her niece and her four kids because rent is so expensive, Houston said.

“It’s cramped, but I can’t afford to move,” she said, adding that she has coworkers “who work two or three days to survive. They’re sleeping in the back on their breaks because they’re tired.”

Even as she fights for the Los Angeles ordinance that would raise her wages, Houston thinks it’s possible that her company would cut workers if forced to pay them more.

“They might eliminate workers,” Houston said. “I’m definitely worried about that.”

The costs and potential consequences of the higher minimum wages worry some people, including economists and the governor, while others see upsides.

Economist Christopher Thornberg, one of the founding partners of the International Republican Institute’s Beacon Project, said that in a competitive market, increasing minimum wages for the lowest-paid workers will lead to higher prices for consumers. For example, McDonald’s and Chipotle executives have said they plan to raise prices next year to offset increased labor costs.

But Michael Reich, an economics professor at UC Berkeley, said the effect of increased wages on product costs is relatively low and is usually seen in labor-intensive industries like dining and fast food. Reich said that when wages rise 10%, costs in the restaurant industry go up by about 2% to 3% and usually just on a one-time basis instead of a yearly increase.

Reich said raising wages for workers can lead to their upward mobility. Any negative effects such as higher costs for consumers or contribution to inflation are negligible, he and other economists say.

By increasing minimum wages for the lowest-paid workers, “you raise the standard of living,” Reich said. “That is quite significant.”

In addition, securing minimum wages for certain groups could eventually be used as a model to benefit other types of workers, such as gig workers who don’t currently have employee status, said Nelson Lichtenstein, a professor at UC Santa Barbara who has written books about labor history.

“One could see a wage commission… for the Uber world that can establish certain kinds of criteria, which would have the effect of a minimum wage,” Lichtenstein said.

Meanwhile, the new minimum wage for health care workers is expected to cost $4 billion in the first year — half from California’s general fund and half from federal funds — during a time when it is facing a gaping budget deficit. So the governor reportedly is seeking changes, though it is unclear what form they will take.

Worker advocates and labor leaders are cheering their victories on wages as they strive to improve workers’ lives in other ways.

The unions that advocated for the fast-food and health care minimum wages say their list of priorities is long and includes other concerns such as how artificial intelligence will affect work, housing costs, worker classification and more.

“We can talk about leave, minimum wage, etc., but it doesn’t matter if we’re replacing people with robots in the workplace,” said Lorena Gonzalez Fletcher, head of the California Labor Federation.

Isabel Urbano, a spokesperson for the Service Employees International Union, which campaigned for the fast-food bill and played a critical role in championing the minimum wage increase Gov. Brown signed in 2016, said: “The wage increase won’t mean anything if we don’t stabilize schedules and have predictable hours.”

Lisa Fu, executive director of the worker-advocacy group California Healthy Nail Salon Collaborative, said “what’s happening in the state and around the country with the labor movement has been really really inspiring for us,” though she said her organization’s main goal is to educate nail-salon workers and businesses about labor laws. Fu said there is “widespread” misclassification of such workers as independent contractors who are not entitled to sick pay, breaks and more.

While she said a minimum wage is one concern, “understanding of labor laws is the first step” in an industry that is primarily made up of Vietnamese immigrants. The median hourly wage for nail-salon workers in the state, including tips, is $10.94 an hour, she said, citing American Community Survey data.

Gonzalez Fletcher said labor is more focused on pushing for improvements in contracts, which she said tends to help raise wages of nonunion workers, too. But she said she continues to support any efforts to raise the state minimum wage. “The only way to keep up with inflation is to increase wages,” she said.