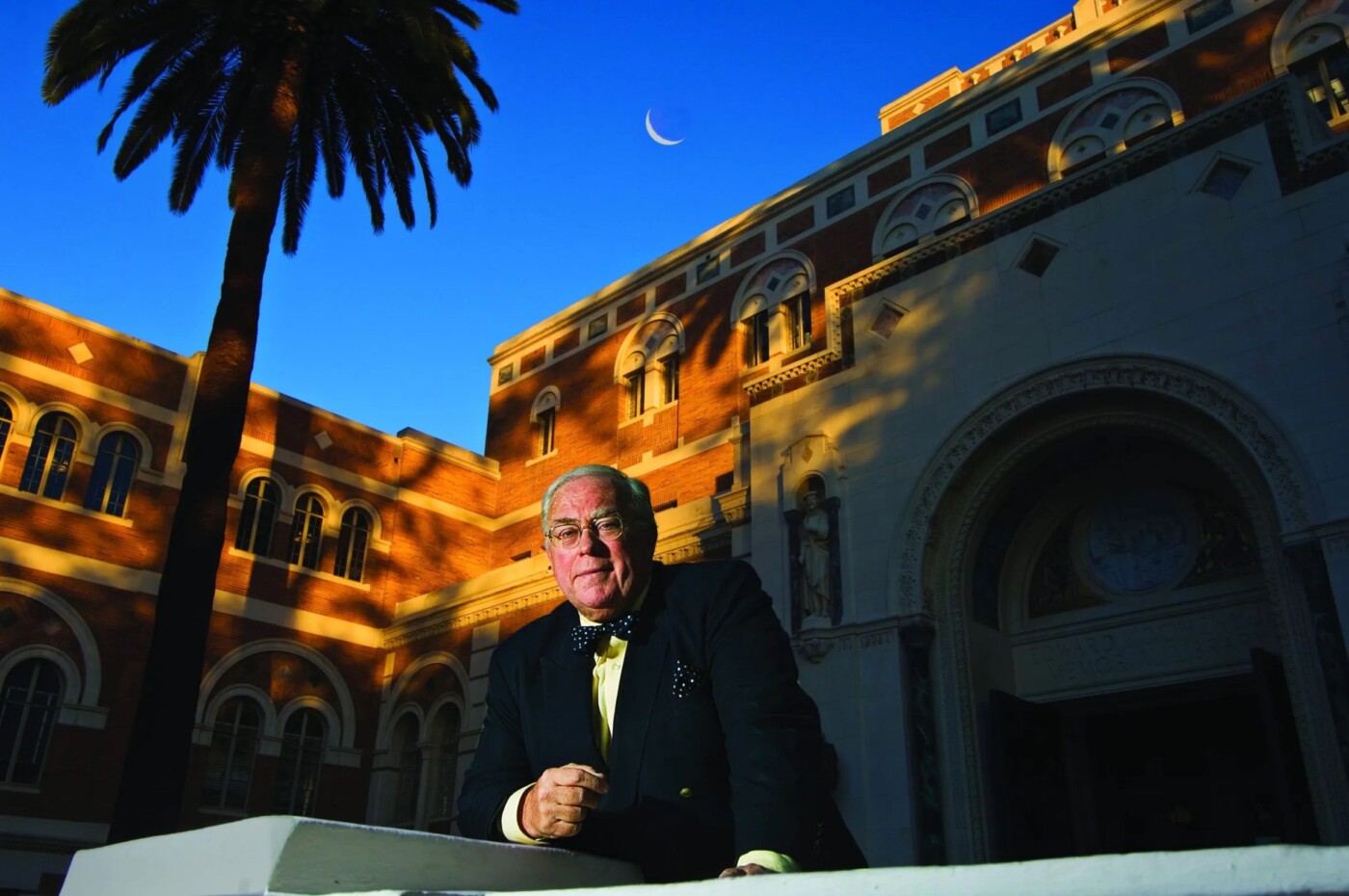

“I live in a city called California,” said historian and librarian Kevin Starr, author of multiple books on the condition of our Far West state. Best known for his eight-book series “Americans and the California Dream,” Starr told stories of our people and place, asserting where we fit in the collective imagination, as well as on the world stage.

“He was trying to hold it all together, from the Oregon border to the south,” says Jason S. Sexton, editor of “Redemptive Dreams: Engaging Kevin Starr’s California” (Routledge, 180 pages, $45), a new collection of essays devoted to what drove Starr’s devotion to the Golden State.

“It was an impossible task,” and a job Starr himself characterized as “foolhardy,” adds Sexton, who appears Dec. 11 at San Francisco’s Commonwealth Club with Bay Area scholars Russell Jeung and Peter Richardson, who contributed to the book, and journalist Julia Flynn Siler.

Beginning in 1973 with “Americans and the California Dream, 1850-1915” and through “Golden Dreams: Californians in the Age of Abundance, 1950-1963,” Starr persisted at wrestling with the contradictions and shifts of California’s cultural and social landscape, investigating and observing its people and phenomenon from the sins of westward expansion and the state’s founding to its notorious booms and busts and tangible exports such as Hollywood and personal computers.

In his distinctive but always readable telling, Starr, who died in 2017, embedded his own story of a California idealist searching for security, adventure and a better world.

Observing our riotous and righteous lifestyles from what seemed to be his catbird seat in San Francisco, Starr documented California’s stature and influence as a magnificent place on the page, while seeking to probe where it fell short on its promise.

His ability to tell stories, weave tales and to craft a narrative rooted in history and threaded with cultural and personal resonance has been characterized as “unparalleled.” In many ways it was ahead of its time, with some asterisks.

“Kevin’s work can bear the critical analysis of historians, sociologists and theologians, he’s using a lot of our language,” says Sexton. At the same time, “He wanted to narrate the positives. I didn’t realize he was a Catholic historian but that became a part of our argument. Kevin would celebrate everything. Every meal. Life.”

What he lacked in citations in his early work, or in his lack of perspective on diversity, has largely been forgiven for his dreams of redemption, for our place, our people and its fathers.

“Story is so important to history and he really was an expert storyteller, at crafting a narrative,” says Sexton. “This was his contribution. Stories are at the root of ethnic studies, labor studies. Oral histories are key.”

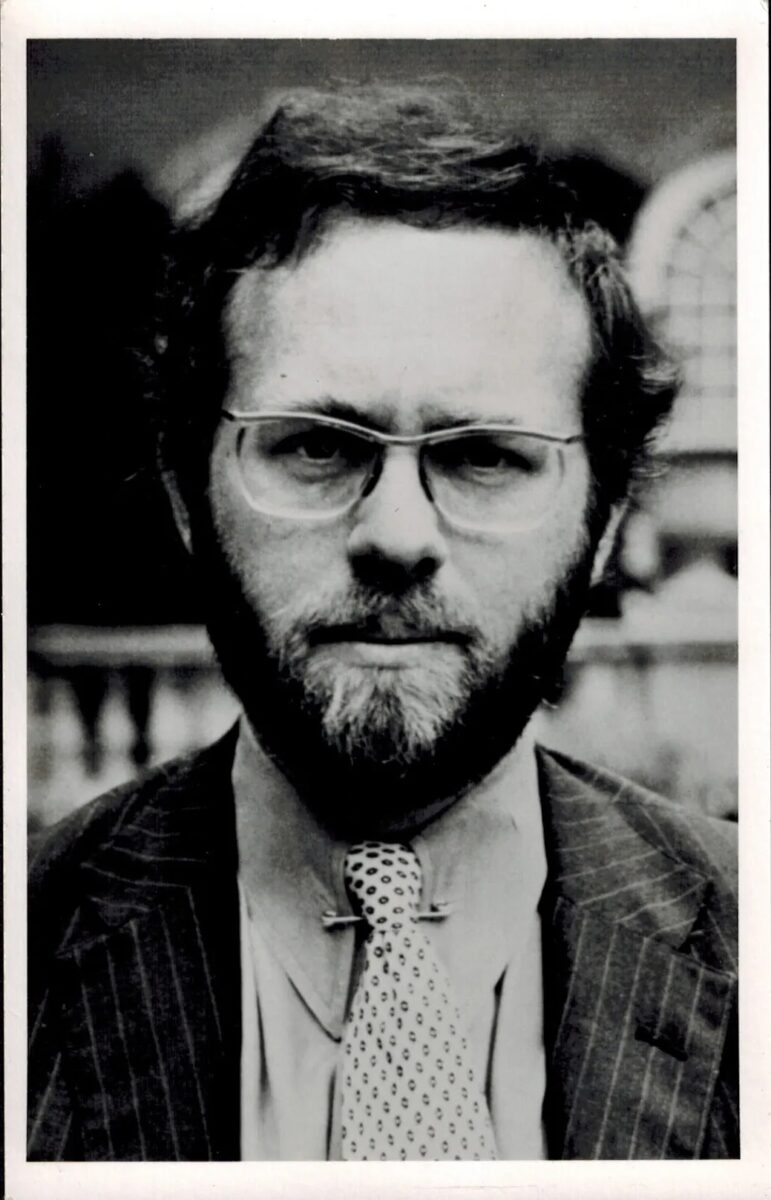

Kevin Starr, who grew up in San Francisco, launched his academic career at Harvard University. (Courtesy Allston Burr, Senior Tutor Eliot House Harvard University 1972)

Writer, scholar and theologian Jason Sexton, editor of the new Kevin Starr collection, has much in common with the late historian. (Courtesy Jason Sexton)

Of course, between the time Starr launched his career as an academic at Harvard University in the mid-1960s, and until his death in 2017, the world inevitably changed, as did he. Now his work is oddly timely as well as ripe for a revisitation.

As a theologian, social theorist and cultural historian, Sexton, also Californian, was doing his own 21st century post-doctoral theological research in the United Kingdom when he became acquainted with Starr’s work and contacted him, scholar-to-scholar.

“I realized pretty quickly that Kevin was the guy to be talking to,” says Sexton. He arranged a meeting of the minds that resulted in 2014’s “Theology and California: Theological Refractions on California’s Culture” and “Redemptive Dreams,” published in November by Routledge.

Among the contributors to “Redemptive Dreams” are San Francisco State University professor Jeung, California historian Mike Davis and Anthea M. Hartig, director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, and former director of the California Historical Society in San Francisco. They are fearless in their appraisal of Starr’s work, in the same spirit of his own. The book is dedicated to Sheila, Starr’s wife and co-pilot of 50 years.

“I asked Sheila whether Kevin’s Catholicism was explicitly part of his vision of California,” says Sexton. “She said it was tacit rather than something he was specifically trying to do,” though once Sexton started looking for earmarks of Starr’s faith in the writing, “It was everywhere.”

Starr was born in 1940 in San Francisco to parents who could not keep him. He and his brother were placed in a Catholic orphanage for five years then reunited with their mother, living on a low income in the Potrero Hill housing projects.

“I think Mike Davis captured it so well in the book, feeling he was unloved by his mother and father,” says Sexton. Davis was Starr’s peer as a California historian. The pair were mutually admiring and respectful of each other’s work and agreed often, despite what may have appeared to be their political polarities.

“Kevin was always talking about the struggle for corrective and collective action and how it’s constant work. There was a real emphasis on the need to protect workers and keep unions strong,” says Sexton. “That was something I brought up with Sheila during the pandemic, wondering how he would’ve responded.”

Starr attended St. Boniface School in the Tenderloin, St. Ignatius High School and the University of San Francisco before heading off to the army followed by graduate studies at Harvard. He returned for an additional degree in library science at Berkeley and worked as city librarian for San Francisco and the state of California.

Inspired by religious figures, anything with a moral center and writers who chronicled life as it was before his time, “he really liked the writings of Father John Ryan,” says Sexton.

Universalist Unitarian minister Thomas Starr King was of interest, as were California journalist Carey McWilliams and the Naturalists, Emile Zola and Frank Norris.

Starr, who taught at Stanford University, University of Southern California, University of California campuses including Berkeley and University of San Francisco, assigned Zola and Norris to his USF students, including this writer, who says, “I remember well his lessons on new journalism and studying books by Joan Didion, Norman Mailer and Hunter S. Thompson. He helped me decide to become a regional specialist, with an interest in what we then called ‘human interest’ and people stories. I took his parting directions from the class as words to live by: ‘Now go and live your life so you have something to write about.’”

There was another side to Starr that can only be described as conservative. Bypassing the late 1960s, ’70s and ’80s in his books, Starr made free with iconoclastic takes in columns for the San Francisco Examiner, where he wrote up to six times a week between 1976 and 1983. This curious period is unpacked in “Redemptive Dreams” with fortitude by Richardson. He calls out Starr for landing on the wrong side of history on watershed cultural moments like the imprisonment of heiress Patricia Hearst (he thought it was punishment for her class status rather than her crime) and the election of the country’s first unapologetically gay politician, Harvey Milk (Starr endorsed Milk’s opponent and his assassin, Dan White).

“And yet, he wrote two columns back-to-back celebrating the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence,” says Sexton, referring to the charitable organization/drag performance troupe that sends up morals and gender identity.

“Even though they upset the Catholic Church and the very conservative diocese, Kevin felt like he had the freedom to think with his conscience. He formed unlikely friendships and felt free to change his mind. He experienced a spiritual change,” says Sexton. “He sees the world as alive and something worth fighting for, even when he gets it wrong. He sees the world as a sacred place, where God is working — that’s the reason we don’t abandon it.”

“Redemptive Dreams” includes a transcript of a lecture delivered by Starr in 2015 at USC, its subject the task of interpreting California which was how he spent his lifetime. And yet, between history as he saw it and a future unwritten, Starr had learned to live in the in-between, in the holy here and now and miraculous present.

“Trust your instincts. Trust your experience,” Starr said. “Trust the California you are encountering at this all-important time in your life.”

Jason Sexton, Russell Jeung, and Peter Richardson appear in “Engaging Kevin Starr’s California Dream, Past Present and Future” with Julia Flynn Siler at 5:30 p.m. Dec. 11 at the Commonwealth Club of California, 110 The Embarcadero, San Francisco. Tickets are $10-$20. For information, visit commonwealthclub.org