About $550 million in federal and state funding for college is left behind annually when thousands of eligible California students miss out on financial aid, but a new California law intended to increase the number of high school seniors completing financial aid applications seems to be working.

In September, the California Student Aid Commission announced that it had received 24,000 more applications than the previous year. These students completed either the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, known as FAFSA, or the state California Dream Act Application, known as CADAA, for students who are ineligible for federal aid due to their immigration status.

In total, California saw a 74% completion rate in 2023, a 9% increase in FAFSA and a 1% increase in CADAA, ranking the state first in the nation for financial aid application growth in the past academic year. California ranks 14th out of 50 states in FAFSA completion.

As California’s push to increase applications enters its second year, upcoming changes to the forms could both help and hinder the effort. The U.S. Department of Education is streamlining the FAFSA, but delays in the overhaul will give students one less month to apply.

Assembly Bill 469, passed in 2021, requires high schools in California to verify that their seniors have completed a financial aid application or an opt-out form. California was the sixth out of 12 states to enact such a requirement. In Louisiana, which saw a 25% increase in FAFSA completion its first year, students are required to fill out an application to graduate. But in California, there is no penalty for students who don’t.

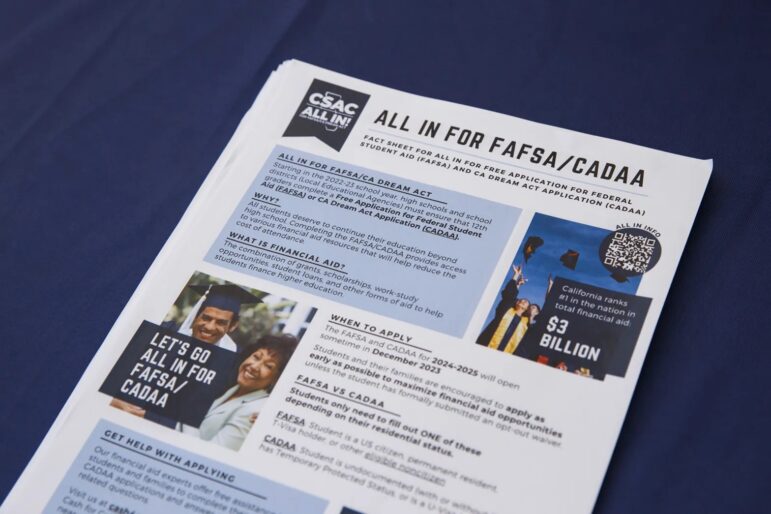

To get the word out, the California Student Aid Commission created the campaign “All in for FAFSA/CADAA” and deployed it through two of its programs, the California Student Opportunity and Access Program and Cash for College.

The opportunity and access program provides college preparation and financial aid assistance to underserved high school students and their parents. The program operates in 16 locations across California, partnering with local colleges and organizations.

“They’re required to work with a certain demographic of students and then, if they have capacity, they can expand beyond that,” said Michael Lemus, outreach and marketing director for the commission.

The program hosts Cash for College workshops at high schools and colleges, and the commission trains high school counselors, student advocates and others who help students apply for financial aid. Last year, the commission hosted 17 statewide webinars and over 1,440 Cash for College workshops.

As many as 1,400 public schools in California saw an increase in financial aid application completion by the Sept. 5 deadline.

One of those was Borrego Springs High School. Located in northeastern San Diego County, the small school has an enrollment of just 124 students. By September 2023, 85% of its seniors completed an application, nearly 20 percentage points more than in the previous year.

Andrea Urquidez, who teaches a senior seminar class at the school, said she focused on informing families.

“We just kind of talked to the kids and let them know that it was something that had to be done last year because of the changes that were made, and that they needed every high school student to apply,” said Urquidez, a community schools coordinator for the Borrego Springs Unified School District.

Urquidez and her colleagues hosted a FAFSA Night within the first month of the application’s release for its class of just over 30 seniors. They opened up the school library with computers, where families brought necessary documents. About 20 students attended.

“We stayed ‘til almost 9 or 10 o’clock that night, just making sure that everybody got it filled out. If there were kids that didn’t come, we followed up with them,” Urquidez said.

Many families at Borrego Springs were surprised that they qualified for financial aid. Urquidez said that living in a rural community, a lot of students don’t think they can afford to go to college.

“We have agriculture workers. We have families here. It’s a very low-income community,” she said, adding that for those with a senior for the first time, “they didn’t know about the financial assistance. So, it was something very eye-opening for them to see and know that this is money that they don’t have to pay back.”

Urquidez says because Borrego Springs is such a small school, she’s been able to build relationships with families who open up about their financial situations. She also helps students look for scholarships.

This year, since the applications won’t be available until December, Urquidez and colleagues plan to email and call families to let them know there will be less time to apply.

Many schools rely on their academic counselors to help students apply for financial aid. However, some counselors say they are already stretched thin.

Rancho San Juan High School, in Monterey County, serves over 1,600 students. The school has six counselors to assist families with financial aid applications, with help from nearby Hartnell College’s financial advisor about twice a year.

In 2023, 69% of the high school’s 460 seniors completed an application, just 3 percentage points more than the year before.

Dolores Christensen, a counselor at Rancho San Juan, said that one of the school’s challenges is the lack of people designated to assist families. According to the American School Counselor Association, the average student to counselor ratio in California was 509-to-1 in 2021-22, while the recommended ratio is 250-to-1.

“Even if we had one person designated … and they are guiding all the efforts, I think that would clearly help us raise our rates a lot better,” Christensen said.

At Escondido High School, counselors had already been pushing all students to pursue college and fill out financial aid applications before the new law.

“We 100,000,000% believe in the power of accessing higher education, and the only way to access higher education is through being able to connect students to financial aid,” high school counselor Xochitl Gonzalez said.

Data from the state aid commission shows that 383 of the school’s 513 seniors completed a financial aid application last year, a 7 percentage point increase from the year before. However, Gonzalez said these numbers may not reflect the full picture, because the school has a sizable number of students, such as those in special ed programs, who are not working towards a diploma.

At this high school north of San Diego, a majority of students come from families living close to the federal poverty line. Many are undocumented, with around 40 seniors submitting a CADAA last year.

The six counselors at Escondido High work closely with students and their families to ensure they complete a financial aid application. They keep track of which students haven’t completed an application or opted out, and call them into their office once a month to find out why. If families are resistant to applying for aid, Gonzalez said they do “everything possible” to convince them. Additionally, they send out constant reminders.

“We’re really annoying,” Gonzalez said. “It works because it gets the vast majority of our students to finish.”

Gonzalez said the department’s efforts would be helped by more clerical support and better internet. The school’s limited Wi-Fi bandwidth, as well as outdated hardware, means that accessing the online applications on computers can be so slow. It’s faster for students to use their cell phones.

With the rollout of the simplified FAFSA planned for this December, along with changes to the CADAA, students and families can expect an easier process. The changes aim to address criticisms that the current FAFSA is too long and complex, and that the financial aid award process lacks transparency and predictability.

The past FAFSA had 103 questions, most of which asked families to parse through their federal tax returns. Now, parts of the application will be either pre-populated with data directly from the IRS, or skipped over if that part doesn’t relate to the applicant. At most, applicants will see just 36 questions.

Claudio Zavala, a first-year business administration student at Cal State Bakersfield, was the first in his family to fill out a financial aid application as he prepared to graduate from Everett Alvarez High School in Monterey County this past year.

Zavala received guidance at a mandatory workshop for seniors during the school day. He said the application was easy until he had to provide tax information.

“I mostly got the information from documents that were provided by my parents. They’re immigrants, so they don’t have Social Security numbers or anything like that. So, it was more of a difficult process,” Zavala said.

Counselors were able to help Zavala analyze his documents and guide him on what to put in the application. The streamlined application this year should make it easier for students like Zavala to apply for financial aid.

Another big change is the factor used to determine how much aid a student is eligible to receive. In the past, the number was called the Expected Family Contribution. Now it will be called the Student Aid Index and be calculated slightly differently. The rebrand aims to avoid the misconception that the Expected Family Contribution represented the amount families needed to pay toward college.

The basic formula remains the same. Financial need equals the total cost of attending a college, minus the index and aid from other sources. New regulations for how colleges calculate their cost of attendance — such as requiring colleges to assume students eat three meals a day, rather than two — might increase the amount of aid students receive.

The overhauled FAFSA isn’t expected to be ready until December, two months later than the usual Oct. 1 release. To account for the delay, California extended the priority deadline to submit financial aid applications by one month, to April 2, 2024. If eligible, students that meet the priority deadline are guaranteed a Cal Grant award, a California-specific grant for students based on financial need and grade-point average. In the meantime, students can still create their accounts on the Federal Student Aid website.

The delay puts pressure on high school counselors to reach students quickly. Urquidez said that Borrego Springs hopes to host FAFSA Night within the first week of the application’s release, before students leave for winter break.

But for the larger Rancho San Juan High School, Christensen said counselors cannot begin helping families until January, after the break. The application period overlaps with Rancho San Juan’s student registration from February through March. The counselors also juggle other responsibilities, such as scheduling, ensuring students are on track for graduation, and crisis management.

“When you don’t have the time really to put into having a really focused effort and launching it from start to finish in a way that you’re constantly addressing it, and constantly monitoring it, that’s a challenge,” Christensen said.

Still, the counselors discuss financial aid applications in government and economics classes, and provide assistance during evening and Saturday sessions with parents.

“If the students aren’t hearing about it, they don’t really take the initiative to do it unless they’re super highly motivated, and they’re resourceful, and they know how to do it,” Christensen said.