One third of Americans over the age of 25 have a bachelor’s degree, an increasingly important dividing line that affects the way that Americans live and die.

Princeton researchers Anne Case and Angus Deaton have a new paper out that looks into the rapidly widening gap in mortality between those who do or don’t have a bachelor’s degree. It is being published for the conference held by the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (BPEA). The authors are economists perhaps best known for coining the phrase “deaths of despair,” which includes drug overdoses, alcoholic liver disease and suicides.

These types of deaths, which rose rapidly after 1992, have become key to understanding the divide between those with and without a college degree. In 2019, the mortality rate for those without a degree more than doubled to 95 out of 100,000 people 25 to 84 years old. The rate for those with a degree is 29 people, compared to 26 people in 1992.

Case and Deaton’s earlier focus on “deaths of despair” was on middle-aged Americans, but they write that is the youngest cohort, aged 25 to 34, who are at greatest risk: “This is an increasingly understood, but still underappreciated fact about deaths of despair, that the young are the worst affected.”

It’s not just about deaths of despair. College-educated Americans have been faring better than those without a degree in just about every marker of mortality. Deaths from cancer and cardiovascular disease have fallen in the last 30 years, but the gap has been growing and it favors the better-educated. The new paper includes pandemic data, which shows that deaths by COVID increased in both groups, but COVID hit the less-educated harder.

Case and Deaton’s findings seem to prove the theory that those with power and resources will more effectively seize the means to prevent death, but what is notable is that this is happening “on steroids” in the United States.

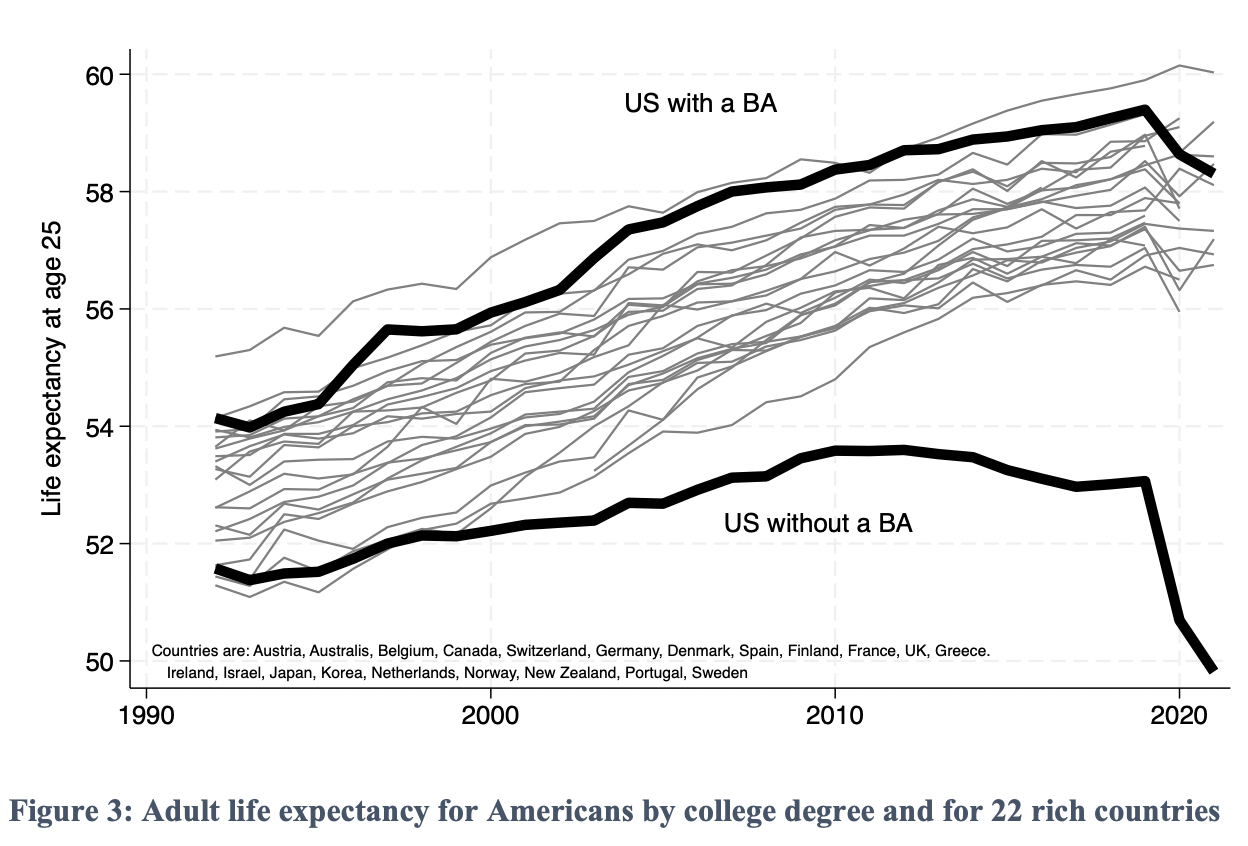

In 1980, life expectancy in the United States was in the middle of a pack of 22 wealthy countries, but since then, it has diverged and is far below the bottom of the pack. Case and Deaton point out that were college-educated Americans their own country, it would be nearly at the head of the pack, just behind Japan.

Case and Deaton note the U.S. is the only country where life expectancies are trending in different directions.

The authors note that there are widening gaps between those with degrees and those without on range of outcomes that include marriage rates, out-of-wedlock childbearing, religious observance, wages, employment as well as death and pain. They call it a “deterioration in the situation of less-educated people in today’s United States.”

In their 2020 book “Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism,” they noted some possible causes: the rise of globalization and automation without a strong safety net, a health care system tied to employment, a decline in unions and an increasing number of business-friendly state laws that harm workers. They also point out that a degree is sometimes used by employers as a way to screen workers rather than hiring workers based on skills.