As students continue to struggle with learning loss in mathematics, some educators are pushing for a return to a more structured teaching strategy that’s being called the “science of math.”

Posited by advocates as a companion to the better-known “science of reading,” a juggernaut that has recently brought enormous change in how that subject is taught nationwide, the “science of math” calls for a more orderly, explicit approach to classroom instruction.

Sarah Powell, associate professor at the University of Texas at Austin and one of the movement’s most vocal proponents, said the circuitous path to learning popularized in recent years might “sound sexy” but doesn’t help kids master the skills they need to succeed — at least not in math.

“Some teachers are helping to set students up for success,” she said, while others are not. “We don’t want to waste students’ time.”

But critics call the movement poorly researched, saying it resurrects ineffective techniques that should have been abandoned years ago. They say, too, that it won’t counter the current mathematics crisis, evidenced by a troubling cascade of low test results at the local, state and national level.

Powell said ineffective teaching practices are among the factors that have contributed to students’ performance. She said many educators, in delivering their lessons, are not getting to the point fast enough, especially considering the limited time in which they must teach complex and often abstract concepts.

Powell, who works in the department of special education, said she observed a fourth-grade teacher last school year who instructed her students, at the start of class, to find a partner and begin to solve a mathematical problem right away, with no prior instruction.

“That can be a really intimidating strategy for a lot of students, especially if they haven’t worked on a multi-step word problem before,” Powell said.

“If you put an adult in that situation, they would be really, really annoyed. And that we put students in that situation is quite unfair, particularly when they have weak or sometimes nonexistent foundations in math.”

Instead, she said, teachers would be better to explain the problem first and arm students with some of the vocabulary they will need to solve it. So, a lesson on perimeter shouldn’t start with students staring at a figure on a sheet of paper, asking themselves and one another about where the perimeter might be found, she said, but with a teacher providing a definition of the term, in this case, the distance around the outside of a shape.

“We would like to see teachers go over vocabulary that’s going to be important or say, ‘Let’s do a problem together,’” she said. “Be more systematic with that than open-ended because it could be that when you do allow students to explore, you might have some students engaging in no exploration … or maybe incorrect exploration.”

Some 25,000 people are members of the science of math Facebook group, where they discuss best practices, share helpful websites and offer feedback on lesson plans. Powell is currently working with around 100 fourth- and fifth-grade teachers in Austin this year.

Nick Wasserman, associate professor of mathematics education at Columbia University’s Teachers College, said there has been much back and forth around the teaching of mathematics through the decades, as evidenced by the math wars of the 1990s.

Part of the issue, he said, is that educators sometimes prioritize different aspects of mathematics and draw differing conclusions from the same studies. But even considering these debates, research has shown students learn better when they are asked to reason and think mathematically — a core tenet of inquiry-oriented approaches.

“Of course, teachers have times when they are giving direct instruction and that is not something we disagree about,” he said, adding that, “But it’s also really important that students have times when they are the ones being asked to think and reason mathematically. Giving students tasks for them to work on on their own — without a teacher telling them how to think — is a vital component of that. A key piece is this engagement with thinking and reasoning.”

Michael Greenlee, who also works at UT Austin as a professional learning specialist with the Charles A. Dana Center, said the “science of math” should be approached with caution.

Greenlee, who serves as a regional director for the National Council of Supervisors of Mathematics, questions the validity of the idea, adding its special education roots might not make it applicable to all students.

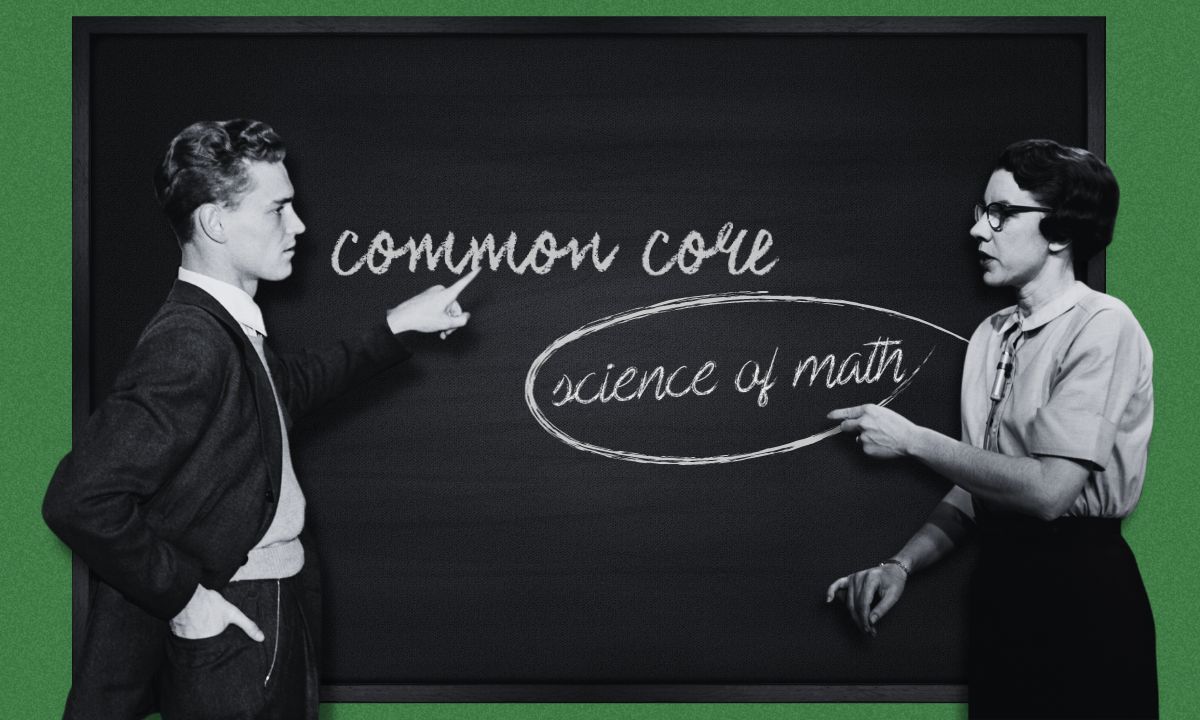

He argues, too, that there is a political agenda behind it, backed with people trying to fight against the Common Core, what they have wrongly dubbed “new math.”

“Common Core illustrates more explicitly what math actually is,” Greenlee said. “People look at it as new math because it’s vocalizing and putting in words brain processes and scaffolding strategies that students should use.”

Powell scoffs at the politicization of the issue and said she is in favor of the Common Core standards, put forth in 2009 and which sought to define one rigorous set of English and math skills that every student should have at the end of each grade level.

Initially widely embraced, the standards, particularly Common Core math, later engendered intense backlash, including from those who considered it an intrusive federal mandate. It was so confusing for parents that it sent them back to the classroom to understand the new techniques.

Greenlee said the “science of math” has no relationship to “the science of reading” and is unfairly linking itself to the earlier movement. He said, too, that the “science of math” assumes teachers are using certain methods when they are not.

“The reality is, we don’t know what teachers are actually doing in their classrooms,” he said. “In fact, in my job going into large systems and school districts, my experience is teachers aren’t doing what that research says they should be doing: They’re still not teaching (mathematics) appropriately. They don’t have the background knowledge themselves to be able to teach it properly.”

Jo Boaler, a Stanford University professor and one of the main architects of California’s recently updated math framework, said many educators are exacerbated by the “science of math” debate.

“They’re rolling their eyes about it,” she said, adding that those who promote the notion have cherry picked data.

She said research shows students learn better — they are more able to master terms and methods — through activity.

“But if you stand at the front and tell them first, it often stops them really being able to engage conceptually because their brains are just so taken up with these methods and rules, they can’t even think conceptually,” she said.

Boaler is no defender of the Common Core standards: She calls them outdated. But this “old is new” tactic, which immediately divides kids into “right” and “wrong”, isn’t the answer, she said.

“Why are we not teaching kids the mathematics they will need in the world they’re moving into?” Boaler asked, adding students should leave high school with data literacy and the ability to build a mathematical model that would allow them to study the issues most pressing to them. “They’re not learning that in school. They’re just learning the calculation piece. When they’re given a real situation and asked to make a mathematical function, they can’t.”

This lack of knowledge places students at a disadvantage compared to those from other countries, she said.

“When we have been out interviewing seniors in high school recently, they had never seen a spreadsheet in their whole 12 years of school,” she said.

“The U.S. is really far behind the rest of the world in teaching kids about data and data tools.”

Such knowledge would have been tremendously useful during the pandemic: Much of the information shared about the virus was done using graphs and statistics, data impenetrable to those who didn’t understand them, she said.

But Elizabeth M. Hughes, associate professor of special education at Penn State said educators do not have to pick a side in the debate.

“A lot of times I see things on the internet that are essentially asking, ‘Are you Team Fact Fluency’ or ‘Team Conceptual Understanding?’” she said. “The reality of it is that students need both. They need to understand the underlying constructs of addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division and be able to do them accurately with ease. Students need to be able to explore new ideas and have a solid plan to solve known problems.”

And, she said, rote memorization might have been wrongly demonized: Students must be able to recall math facts with ease and accuracy.

“That shouldn’t be a controversial idea,” she said.

Wasserman said teachers can find success through many strategies — including a combination of guided instruction and student exploration.

“It’s fine to give students a definition,” he said, but teachers must also give them tasks “that force them to wrestle and grapple with some of the nuances of that concept.”