Even by its own lofty standards of activism established over many decades, it has been a remarkable few days at Berkeley High School.

Over the years the school has been a leader in protests against the Vietnam War, against apartheid in South Africa and against global warming.

Now the #MeToo movement against sexual assault and harassment has come to the school, too.

The school has been riven by an outpouring of testimony about what students viewed as the school’s inadequate response to accusations of sexual harassment and even assault by fellow students, including off-campus incidents that can have an impact on student interactions, learning and relationships on the campus.

Under the federal Title IX law, education institutions are required to create an environment free of sexual harassment. The district’s own policies say that it is committed to “providing an educational environment free of unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature.”

Now students are demanding that the district hire a full-time Title IX officer specifically for the high school and hire two full-time “restorative justice” counselors with “expertise in sexual harm.” Other demands include training all students beginning in the 6th grade — middle school — in sexual consent.

“Berkeley as a whole is a very liberal place,” said 17-year-old senior Abby Sanchez, one of the protest leaders. “But it is one thing to say ‘We have a culture of healing survivors,’ and it is another thing to have policies in place to protect them.”

With over 3,000 students, the school, with a largely female leadership, is the only public high school in Berkeley, a community of about 100,000 people best known for its public university just blocks from the high school.

“Our whole admin team has spent time listening to students, in large groups and often one-on-one, and hearing their pain and anger as well as their requests and demands for change,” wrote principal Erin Schweng in a statement sent out to parents on Wednesday evening. “It has been heartbreaking.”

After years in which most attention has been focused on sexual harassment and assault on college campuses, the protests brought to the surface the arguably even more complex issue of how to deal with these issues on high school campuses.

To a far greater extent than on college campuses, high schools have to contend with far stricter privacy rules because they are dealing for the most part with minors. Another complication is that, unlike college, high school students aren’t living in campus-related housing, and their schools have much less control over or responsibility for what happens at off-campus social events. In many cases harassment and assault take place off campus but then victims have to deal with the perpetrators at school, sometimes in their own classrooms. Schools, in turn, are constrained because they can’t suspend or expel students for off-campus incidents and behavior.

Helping to set the protests in motion was a lawsuit filed last week by a Berkeley High student who alleged that she had been the victim of an attempted rape on the campus, and that the school, among other things, had not provided enough oversight and supervision of students and mishandled the alleged assault by not reporting it to the police or Child Protective Services.

A few days after the lawsuit was filed, Berkeleyside, an online news site that has provided the only sustained coverage of the protests, quoted Berkeley police as saying that they had in fact been notified by the school.

About the same time news of the lawsuit emerged, the names of several boys appeared in black marker in a girls’ bathroom at the school, with the warning “boys to watch out 4.” “Support each other always,” the sign read. “Add names if you want.”

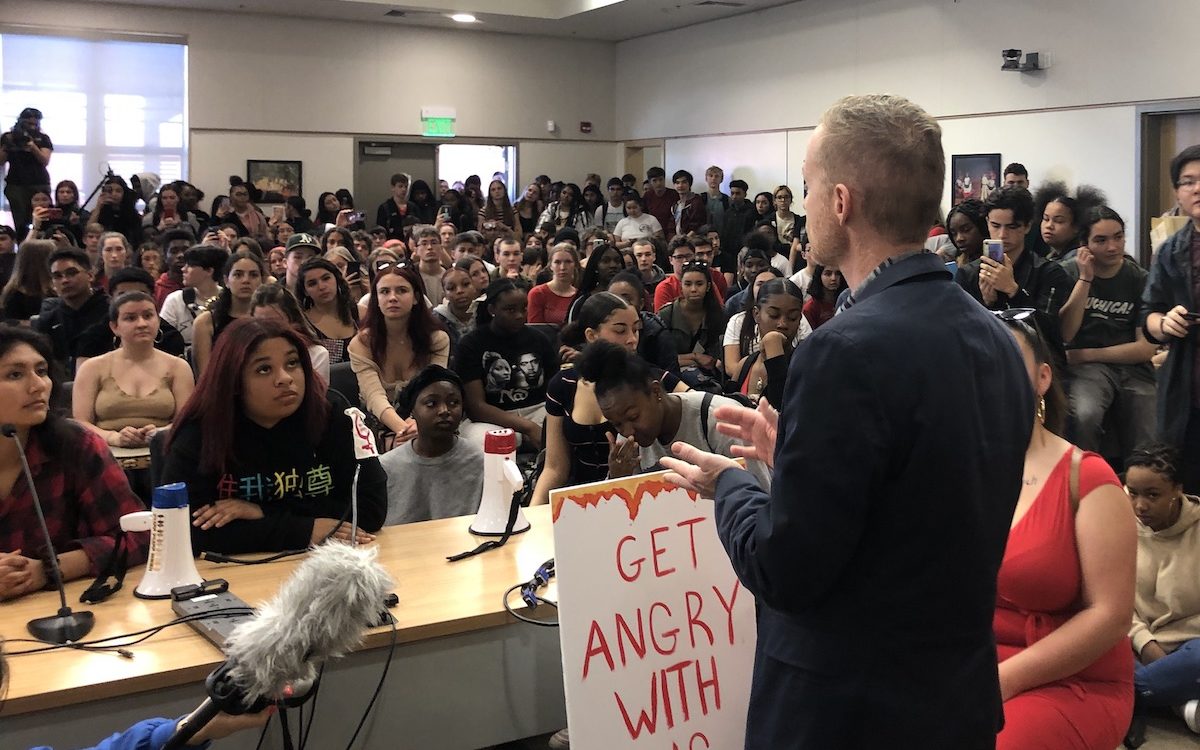

That led to a walkout of students, which then morphed into an all-day sit-in at a park adjoining the school in which students related stories of assault, abuse and harassment in their own lives. The next day students marched to district headquarters and engaged in an emotional dialogue with Brent Stephens, the district’s new superintendent, who has been in his post only since last July.

Stephens sent out a statement later that day, describing some of the steps taken over the past several years to protect students. These included updating violence prevention education in the 9th grade, introducing Green Dot, a program about sexual violence, adding intervention counselors and investigators to the district’s complaints office and training staff on compliance with Title IX. Just last month, the district put up posters in bathrooms and locker rooms with information on how to report any incidents of sexual harassment.

He said that even when incidents occur off campus “administrators go to great lengths to ensure that the campus remains a safe place.” Sometimes, he said, students are suspended or expelled, but the school “can’t share with students or parents how they are responding,” due to strict privacy laws.

“This is a very challenging dilemma that we can’t easily solve,” he wrote. “Still the school, district and community can do more.”

“It is important to acknowledge and respond to our students’ feeling that we, the adults who take care of them, have done nothing to support them with this issue,” he wrote.

His letter was met with skepticism by some student leaders. “He meant that email to appease the public and to say ‘Don’t be so mad’ and to take away the focus of what needs to be done,” Berkeley High senior Sanchez said. “My biggest concern is that people will say ‘They did these four things, they did their best, so we should stop protesting.’”

Late this week, principal Schweng indicated that within the next few weeks the school will begin making classroom presentations covering sexual consent, how to report sexual assault and other topics, especially in 10th-to-12th-grade classes, because, she said, these issues are already covered in 9th-grade “social living” classes.

The school would immediately also bring in outside experts from Berkeley who are “specifically skilled at working with students to restore the harm that sexual assault has caused.” Participation would be entirely optional in what Schweng described as “a deep process to create accountability and begin healing.” The district would also begin looking into additional stories and reports of sexual harm that have come up during the days of protest. “We are following up with every student who has come to speak with us,” she wrote.

Next week student leaders say they will present a “final list of demands” to the school board. And that there will be more protests and sit-ins.

“I would like to see policies that care more about protecting the survivor than protecting the perpetrator,” Sanchez said. “The fight has just begun.”